Imagine it’s Sunday morning inside a church somewhere in Utah, and a crisply dressed young man sits in a pew waiting for services to begin, scrolling on his phone.

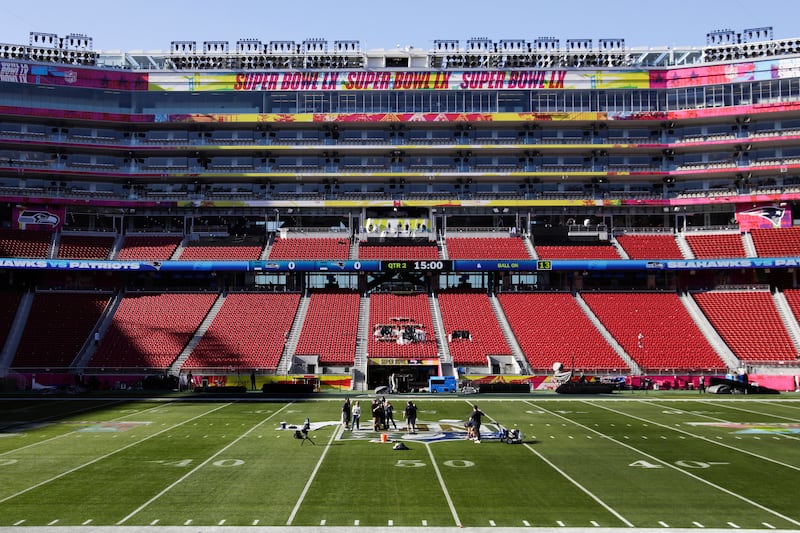

He opens an app called Kalshi. Or Polymarket. Or Fanatics. Any one of the “prediction market” platforms that have become available in Utah in the past six months. He’s a sports fan, and this Sunday happens to be the Super Bowl. He thinks Seattle is going to take it. The chances he’s right are 67%, according to the app. So he presses a button and “purchases an event contract” for $5 that, if Seattle loses, will be lost; and if Seattle wins, will pay $8.

Then the young man puts his phone away and prepares for services to begin without a tingle of doubt or shame, because this transaction is absolutely not gambling.

Or so the industry supporting it would have him believe.

Prediction market companies have worked very hard to make certain of that. They’re very careful with their verbiage; “investments,” “contracts” and “markets” replace “bets,” “odds” and “bookies.” They’ve cultivated important strategic partnerships with news outlets and politicians alike.

Marketing positions the apps as something distinct from traditional sports betting — as something more than mere entertainment. They’re investment tools. “Like stocks, bonds, mutual funds. But they’re not,” said Timothy Fong, a leading addiction psychiatrist and gambling researcher at UCLA. “This is gambling.”

Right now, there’s little appetite — or ability — to combat this interpretation of prediction markets, in Utah or anywhere across the country. At the legal, regulatory and even social level, prediction markets are thriving. Kalshi alone saw trading volume reach $1 billion per week in December — 1,000% growth since the summer of 2024. The company was then valued at $11 billion and struck a formal partnership with CNN, among other media outlets.

With so much money involved, taking action against prediction markets will be challenging, which, in practice, means a new dawn for gambling in the United States. “Doing something about it is very difficult when there’s no pressure,” Fong said. “When every major institution in society — media, sports organizations, governments — are all saying it’s fine.”

This tension between what predictions markets are, functionally and morally, and how their parent companies would like them to be seen has, however, led to a flurry of accusations and lawsuits across the nation, including Nevada and Arizona, hinging on the question of whether prediction markets are a form of “gaming,” which is regulated by individual states, or trading, which is regulated by the federal government.

“I think it has to end up in the Supreme Court,” said I. Nelson Rose, a professor emeritus of law at Whittier College who has studied gambling law for decades. “You’re getting decisions involving so many states and even Indian tribes that only the U.S. Supreme Court can decide it.”

Should prediction market backers prevail, gambling by another name would be allowed to proliferate in Utah, regardless of the state’s long-standing constitutional ban. That provision would be rendered functionally irrelevant — a vestigial clause from a bygone era. And it may already be too late to stop it.

With so much money involved, taking action against prediction markets will be challenging, which, in practice, means a new dawn for gambling in the United States.

Kalshi, courtrooms and clashes to come

Prediction markets operate within a world of potential outcomes. A margin of victory. An individual’s performance. Like LeBron James scoring 25, or BYU beating Texas Tech in the Big 12 Championship. Or even whether the Fed will raise or lower interest rates, and by how much.

Predictions, with cash stakes, can be made on literally anything. You can “invest in” the odds of geopolitical issues. Or today’s weather. You can “trade” on the average number of measles cases that will arise in the next two years. And just like with traditional sports betting, you can combine your “investments,” meaning you can purchase multiple contracts that, if they all prove correct, result in a larger payday. Just don’t call it a parlay. This is a “combination contract.”

The back end of prediction markets does function differently from traditional sports betting operations. Companies like Kalshi don’t work like sportsbooks; there is no “house edge,” where odds are set to ensure profit. Rather, they charge transaction fees to facilitate exchanges between buyers on opposite ends of contracts. Prediction markets also offer percentages rather than odds. But the user experience is almost identical.

“We’re talking about variations of black,” said Victor Matheson, a professor of sports and gambling economics at the College of the Holy Cross. “Is it black? Is it charcoal? Is it ebony? There are slight differences, but functionally, these are the same thing.”

Kalshi CEO Tarek Mansour, however, denies the connection, saying that prediction markets like his function not as casinos, but as financial markets. Some experts agree, at least on some level. “He’s absolutely right,” Rose said. “That is why… (long-standing laws) expressly said that all state anti-gambling laws don’t apply when something is traded on a national, federally regulated exchange.”

In the thick of the Great Depression, Rose explained, Congress passed a series of laws designed to differentiate trading from gambling. The legislation effectively invalidated state-level anti-gambling laws as they apply to federally regulated exchanges.

Prediction markets, for example, are regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, or CFTC. “States historically had been the only ones to decide their public policy toward gambling, and Congress wanted to legalize and regulate stock markets and commodities markets,” Rose added. “So they passed statutes that said if the trade meets specific standards — and they’re somewhat general, but there are words like ‘not gambling’ in there — then the state anti-gambling laws don’t apply.”

This federal law that differentiates trading from gambling as a federal matter is nearly 100 years old. But investing in futures contracts on who might win the Super Bowl, or the Oscars, or anything else — that’s all relatively new, spawned in the last several years, resulting in near-exponential growth for the industry: At the beginning of 2024, monthly trading volume in prediction markets sat around $100 million. By the end of 2025, it had surged to over $13 billion — nearly 13,000% growth. Some believe that growth could be exponential.

“‘Kalshi’ is ‘everything’ in Arabic,” Mansour said at a conference last year. “The long-term vision is to financialize everything and create a tradeable asset out of any difference in opinion.”

Sports “trading,” however, is still king — for now. Scot McClintic, COO of betting and gaming at Fanatics, has overseen his company’s launch of a prediction market platform that, as of December, became available in D.C., Utah and 22 other states. He can dive deep into the technical differences between prediction markets and sports betting, but he also admits there’s plenty of overlap. So much so that Fanatics has built in risk management tools that affect both sides of the coin automatically; if someone sets a $100 limit on sports betting, for example, Fanatics will automatically set a $100 limit on its prediction market platform as well.

Given the similarities between prediction marketing apps and sports betting apps, he’s been surprised to find that many Fanatics users like the fact that the company offers both. “You would think that these products would be substitutive,” he said. “What we’ve seen is actually the opposite. They’re very complementary, and they’re solving a different problem for customers.”

That problem, as he understands it, is this: There are only so many relevant sporting events in a day. Prediction markets offer chances to “trade” on events outside prime-time viewing windows. “Wouldn’t it be great if I could speculate on the amount of snow that’s going to fall on the mountain today?” he asked, in the midst of a major Utah snowstorm. “Things like that, that kind of gamify real-world life, I think that’s what most customers want.”

And in states like Utah, where traditional sports betting remains banned, prediction markets can solve that “problem,” too. All while creating new problems to solve in the courts.

At the beginning of 2024, prediction markets’ monthly trades were around $100 million. By the end of 2025, they surged to over $13 billion.

Unlikely alliances, uncertain outcomes

The first lawsuit came in 2024, brought by the CFTC against Kalshi. The specific case involved prediction market contracts for the 2024 election, which the CFTC determined were both gaming and a threat to election integrity.

U.S. District Court Judge Jia Cobb, however, sided with Kalshi.

The contracts offered were not gaming, she concluded, because elections are not, themselves, unlawful nor gaming. “Which, of course, is ridiculous,” said Rose, law professor and gambling expert. “It is gambling itself. It doesn’t matter. That would be exactly like saying sports betting is not gambling because you’re betting on a football game, not on a roulette wheel.”

But that’s exactly what some prediction market proponents are shooting for: a redefinition of what gambling is and what it isn’t.

States from Massachusetts to Nevada are fighting back. As of January 2026, three prediction market platforms are involved in more than 20 ongoing legal disputes across the country. Lawsuits and cease-and-desist letters have been filed in 11 states, and by several tribal governments.

Their basic argument is that prediction market platforms shouldn’t be allowed to use the federal loophole to skirt state regulations and taxes, since states are supposed to be able to regulate gaming. Results so far have been mixed.

In Massachusetts, a judge issued an injunction against Kalshi, saying the company took an “overly broad” approach to federal law and that Congress’s Securities Exchange Act of 1934 never intended to usurp state authority over gaming.

In Nevada, a judge sided with Kalshi and allowed the company to continue operations in April — only to reverse course in November, arguing that Kalshi’s position “upsets decades of federalism regarding gaming regulation, is contrary to Congress’ intent … and cannot be sustained.” As the lawsuits march on through courts and appeals, though, state legislators are nearly powerless.

Nevada depends heavily on gambling to support its economy, and the threat posed by prediction markets is nearly existential.

“What is being conducted on prediction markets in Utah, in Hawaii, in California, in Texas, in Nevada — it’s gambling,” said Mike Dreitzer, chair of the Nevada Gaming Control Board. “It’s gambling, and it’s an end-run around the well-established principle that gaming is a state choice.” He’s led the charge to file suit against Kalshi, with the backing of many of his state’s most powerful politicians, including both of its senators.

“It’s past time for the CFTC to enforce their own rules against allowing event contracts that involve gaming and protect the American people from these companies,” Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto, a Democrat, said.

Prediction market companies have worked very hard to make certain they aren’t considered gambling. Words like “investments,” “contracts” and “markets” replace “bets,” “odds” and “bookies.”

Given their polar opposite stances on gambling, Utah and Nevada surprisingly find themselves at the table together, rooted in a mutual belief that states should be able to regulate gambling. “These markets are regulated by the CFTC, which thus far has preempted state laws against gambling,” Mike Lee, Utah’s senior senator, said in an email to Deseret Magazine. “I don’t think that sort of loophole is what the CFTC was created for, and indeed, several states agree, and are fighting for the ability to ban prediction markets through their gambling laws in federal court.”

Should those states fail, Lee said the stakes for Utah would be just as existential as for Nevada. “It would mean that Utahns are essentially blocked from representing their own values about gambling in their state laws, and that’s a bad thing,” he said.

Utah state Rep. Joseph Elison, R-Washington, another Republican who agrees that prediction markets can be used to gamble, plans to introduce legislation this year to close a prop betting loophole. But he can’t introduce similar legislation to keep prediction markets out. Nonjudicial solutions would have to involve working with the federal government to redefine gaming to include prediction markets. “It’s a tough battle because there’s a ton of money in these,” he said.

Not least of all for President Donald Trump himself. His social media company announced plans last year to integrate prediction markets into its Truth Social app. His son, Donald Trump Jr., also became a paid strategic adviser to Kalshi just one week before his father was sworn in for his second term.

Trump’s connections to the industry are the wild card looming over all these court cases, Rose said. But he’s still optimistic the Supreme Court could ultimately strike down the current iteration of prediction markets, with several conservative justices potentially swayed by states’ rights arguments.

That change could be a harder sell, however, to a public becoming accustomed to the platforms. “It’s like the frog in boiling water,” Frank Fear, a professor emeritus of community development at Michigan State, said. “You don’t realize the change until it’s pretty much enveloped you.”

The tension between what predictions markets are, functionally and morally, has led to a flurry of lawsuits and threats in states across the nation.

There’s market deference in general, too. Markets are trusted as instruments of freedom, democratization and choice. But left to their own devices, they can also prove destructive by shifting the burden of defining good and bad from society to individuals, deepening fracturing and polarization. “And unfortunately,” adds Fear, “the train has already left the station.”

At a time when 87% of Americans see polarization as a threat, outfits like Kalshi and Polymarket are asking people to add cash stakes to political elections.

The question is, what does each state really want to do about it?

In a statement to Deseret Magazine, Utah Attorney General Derek Brown was vague. “Since Utah’s statehood, gambling has always been prohibited under the Utah State Constitution. This prohibition includes both traditional in-person betting, as well as any online platform that simulates wagering,” he wrote. The statement came specifically in response to an inquiry about prediction markets, though, which the response didn’t directly mention.

Would prediction markets fall under “any online platform that simulates wagering”? That continues to depend on who’s being asked. Sen. Mike Lee says they should. “Prediction markets are clearly a form of gambling,” he said, “simply with an inventive mechanism to work around gambling laws like Utah’s.”

But the question’s final answer in court holds stakes that are both seismic and semantic, with enormously consequential outcomes hinging on narrow definitions. For now, wagering remains, and the odds are stacked.