As many observers have noted, the pandemic has brought the issue of internet access into focus.

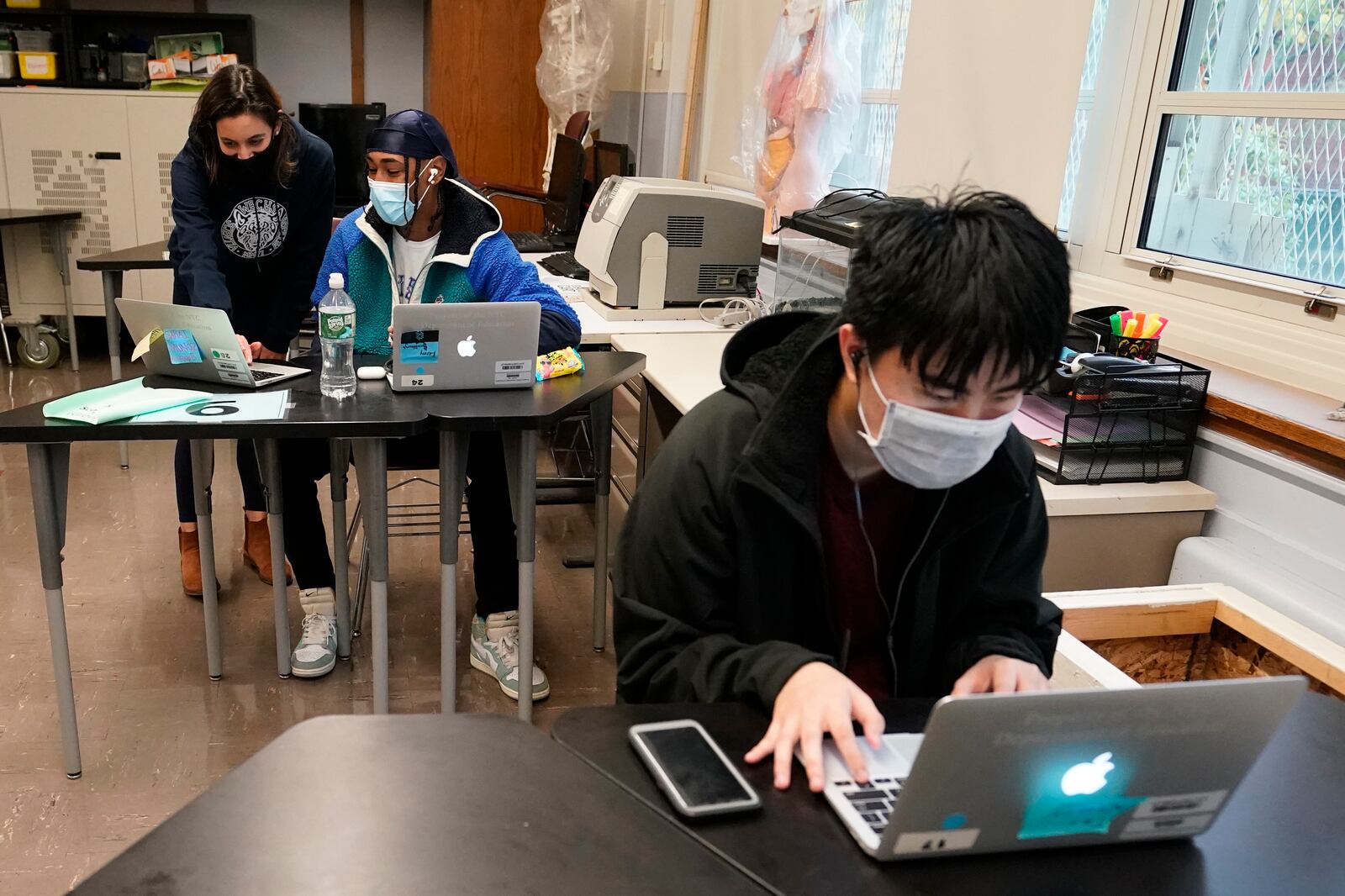

While the wealthiest segment of the population has been logging into Zoom meetings and setting up home offices, many others have struggled to get their children to participate in online schooling because of inadequate equipment. Still others have no connection at all, leaving them unable to enjoy the relative safety of online shopping, participate in telehealth or experience much human interaction with anyone outside the home.

The question for many is, why shouldn’t the government turn internet connectivity — the fiber-optic cables and other transmission lines — into a public utility? If the internet were treated the same as electricity, wouldn’t more people have access, and wouldn’t providers be forced to serve low-income people or rural areas where profit margins are slim or nonexistent?

Unfortunately, solutions aren’t so simple, nor are they free from unintended consequences. Neither are the examples frequently cited so convincing. Government solutions aren’t necessarily the most efficient.

A study of 20th century rural electrification by the Technology Policy Institute shows it took about 25 years of public subsidies to bring rural American areas from a point where 10% of homes had electricity up to 70%. By comparison, it took private broadband industries 15 years to make that same progress.

Bringing broadband to rural areas is taking long enough already. The idea should be to find the fastest route for finishing the job.

Making an industry public also tends to dampen innovation. Power companies continue to raise rates, while innovations come slowly. The history of telephone service can be instructive. Until the government broke up the Bell systems in the early ’80s, little had changed in telephone services in decades. It took several innovators from outside the traditional wired phone industry to bring us where we are today, with frequent daily video calls and smartphones in pockets.

If internet transmission is to become a public utility, it must be done in a way that fosters competition, rather than suppresses it. Utah’s UTOPIA system offers an intriguing example of this. It provides a fiber optic system to many communities, allowing several service providers to compete on that system for business.

But UTOPIA comes with a price, and it had to overcome several years of struggles to get where it is today.

Making broadband service a public utility would not erase the underlying expenses involved in serving difficult-to-reach customers. Nor would it solve the problem of low-income people not being able to afford computers, smartphones and other equipment to utilize the utility.

The best answer lies in finding ways to foster competition, perhaps awarding subsidies to companies that demonstrate they are best able to handle rural connections or to cover other gaps in service. Competition must also be fostered within established communities, where consumers frequently face only one or two choices for broadband service.

When it comes to schooling, plenty of solutions should be explored before saddling taxpayers with another inefficient utility. Yes, internet service has become a key to thriving in the 21st century. But governments should be careful to find the best way to provide that without harming innovation, competition and access.