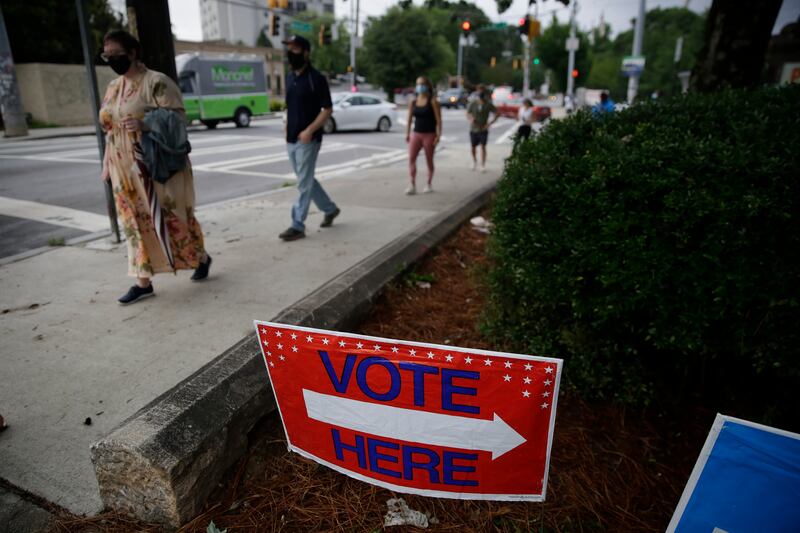

In the Deep South, where the suppression of black votes is a dark part of American history, Georgia’s primary election this week was as troubling as it was astounding. In precincts where minorities are a majority, long lines snaked down streets, people who had requested absentee ballots did not receive them and were not allowed to vote in person, and confusing new voting machines caused troubles.

Americans need to wonder, was this an isolated set of circumstances in one state, or was it a harbinger of things to come nationwide in November?

For the good of the nation, Americans need to insist these problems are solved before then.

In a report on the possibility of a nationwide effort to sow doubt in American elections, Deseret News Washington reporter Matt Brown this week quoted experts on the importance of maintaining public confidence in the election system. “If you don’t have that,” Richard Hasen, a professor of law and political science at the University of California Irvine said, “then you don’t have a democracy.”

The Republican National Committee and President Donald Trump’s reelection campaign has pledged to gather thousands of volunteers to watch polling places in November, searching for fraud in various forms. This follows after members of both parties who lost in 2018 tried to make unsubstantiated claims of irregularities.

Such claims are hardly new to the republic. However, nothing can be more damaging to the nation than a widespread loss of faith in the method by which people choose their leaders. That ultimately could lead to violent protests and accusations that people are assuming office illegitimately, weakening the nation from within.

But it also could be a shrewd strategy for any candidate who loses a tight race,

In the United States, elections are local matters. Even the presidential election exists as a series of small elections, nearly always governed by a county, that add up to a larger state tally from which electors are chosen as part of the Electoral College. This system has its virtues. Large-scale fraud is more difficult in such a fractured system. Surgically applied small-scale fraud in key precincts, however, could change outcomes.

Such allegations were the basis for complaints that the John F. Kennedy-Lyndon Johnson ticket might have altered election results in Chicago and parts of Texas in 1960. While investigators found some instances of fraud back then, Richard Nixon put an end to the probes and conceded defeat, thereby quieting concerns that might have damaged the nation.

Such investigations typically find little hard evidence of fraud, but allegations alone can plant seeds of doubt in an electorate, especially if an election results in a small margin of victory.

This year’s elections are complicated by a pandemic, which makes in-person voting a health risk. Anti-racism protests, focused on the death of George Floyd, also puts a spotlight on irregularities that affect minority voters more than any others.

Add in allegations that foreign operatives may be trying to alter election outcomes, and you have a recipe for a potential electoral disaster. As Hasen said, people need to have enough faith in the system that they can accept defeat and begin focusing on the next election.

That outcome should be the overriding goal for every state and county election official. Neither racism, deliberate fraud on behalf of a candidate nor foreign interference should be allowed to cloud the results this fall.