The controversy over our public monuments could use a dose of wisdom from the old saying, “Don’t remove a fence until you know why it was put up in the first place.”

In the South, where many Confederate memorials were erected as defiant symbols of segregation, change is long overdue, including the removal of Confederate emblems from the state flag of Mississippi, and ongoing efforts to change the name of Montgomery’s Jefferson Davis High School, where 94% of students are African American, the descendants of those whom the Confederacy fought to keep enslaved.

But elsewhere, indiscriminate destruction and unlawful vandalism of monuments to our forefathers reveals a frightening erosion of our shared civic identity and a dangerous dogma permeating the teaching of our nation’s history. Opportunistic looters do not destroy statues; indoctrinated students do. Such mob attacks on public memorials are antithetical to American values not only because they are lawless and anti-democratic acts of violence, but also because they ignore a fundamental essence of the American spirit.

In the beloved patriotic hymn “America the Beautiful,” this essence is described in a powerful and poignant prayer, “God mend thine every flaw.” Abraham Lincoln also captured this sentiment by describing America as an “almost chosen people.” America’s legacy is neither exclusively of saints nor sinners. Its exceptionalism, in ebbs and flows, lies not in self-proclaimed perfectionism, but in ever-striving idealism. America has always been an experiment of self-government by the imperfect. Its aim, says the Constitution’s preamble, is a more perfect Union.

“Sometimes it is said that man cannot be trusted with the government of himself,” Thomas Jefferson said in describing the then-prevailing view of aristocratic monarchy. “Can he then be trusted with the government of others? Or have we found angels, in the form of kings, to govern him?” Our constitutional system of checks and balances was built on the premise of the fallibility of humankind.

Shall we now tear down its architects for having flaws themselves? What statues can survive the scrutiny of infallibility? And who is blameless to cast the first stone?

It is said the greatness of America can be found in its goodness. It can also be found in its capacity to overcome. America’s most defining heritage has not been to have lived without sin but rather to have triumphed in spite of it. Nowhere is this more evident than in America’s history with slavery, segregation and racial inequality.

At the time of its founding, America had inherited from its British forbearers a deeply entrenched institution of human bondage, the scourge of every empire in every age across the globe. There is cruel irony in the reality that the author of the self-evident declaration that “all men are created equal” was a slave owner. And yet, that Heaven-inspired declaration of truth would become the foundation for “a new birth of freedom” bringing about the abolition of slavery in America. Rather than disparage Thomas Jefferson for not living up to the Declaration’s highest ideals, we might instead marvel that someone compromised by the wickedness of slavery would be the means of delivering the most powerful argument against it.

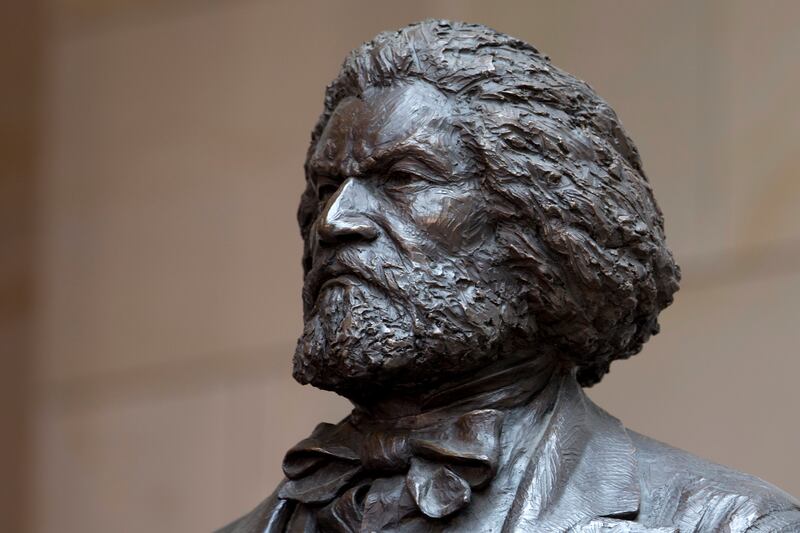

If anyone had cause to give up on America for falling short of its ideals, Frederick Douglass did. Douglass escaped the slavery of his youth, but he never escaped prejudice as an adult. The Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision declared Blacks as “beings of an inferior order” who had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” When he heard Abraham Lincoln, in his first inaugural address before the outbreak of war, promise to defend the constitutional basis for returning fugitive slaves to their masters and not to interfere with slavery “in the states where it exists,” Douglass was ready to give up on his homeland and emigrate.

But something within him sensed “eternal principles” and “invisible forces” shaping the national destiny. He would soon witness the emancipation of millions of slaves, the enlistment of thousands of black soldiers in Union armies, and the passage of the 13th Amendment purging the Constitution of its “original sin” of slavery. He would also witness the same Lincoln, in his second inaugural address, describe slavery as a Biblical “offense” and the Civil War as the “woe due” to both North and South as the righteous judgment of a “living God.” He would be the first person of color to attend an inaugural reception at the White House, where Lincoln would greet him as “my friend Douglass” and desire to know what he thought of his speech, telling him there is “no man in the country whose opinion I value more.”

A century later, from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. would have cause to remind America that, despite emancipation, “the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.” There, in front of a nationwide audience, he described his “dream” for racial equality. Within two years, after more long-suffering marches in the face of bombings and brutality, the conscience of the nation had been changed forever. In the aftermath of “Bloody Sunday” and the marches on Montgomery, Lyndon B. Johnson asked Congress to pass another landmark civil rights bill. When the president, no stranger to racial prejudice and profanity, even adopted the civil rights anthem, “We shall overcome,” King, watching silently, welled up in tears.

America, of course, continues to wrestle with the legacy of racial inequality. But with history as our guide, we might yet overcome more of what continues to divide us. Great leaders of the past extended charity for the weaknesses of their fellow citizens, knowing they needed grace themselves. Rather than pulling down those in the past who had not the benefit of the trials that have refined us as a nation, we might instead ask for the strength and wisdom to be better ourselves.

America, God mend thine every flaw.

Michael Erickson is an attorney in Salt Lake City.

Correction: A previous version mistakenly said Frederick Douglass escaped slavery as a teenager. He was in his early 20s.