The Deseret News/Hinckley Institute survey this week is, for the first time in election 2020, based upon likely voters. So, it seems like an appropriate time to comment on the challenges facing pollsters in figuring out who is likely to actually show up and vote.

The reality is that projecting likely voter models is more of an art than a science.

The first is that millions of voters across the nation don’t know themselves whether they will cast a ballot this year. After all, we live in a world where about one-quarter of all registered voters don’t think things would be all that different if Hillary Clinton had won in 2016. These voters are not just deciding which candidate they dislike the least — they are also trying to decide whether it’s worth the effort to vote. Will it make any difference?

Perhaps something will spark their interest in a particular election, or maybe some campaign will connect with them in a meaningful way. President Trump energized many such disengaged voters in 2016, and that’s the reason he’s in the White House today. Maybe he can do it again, or maybe he will energize many others who sat out the 2016 election.

But it’s not just the disengaged voters who are hard to predict.

Pollsters typically ask survey respondents about their voting intentions and interest in the campaign. This is very helpful in weeding out registered voters who are clearly disengaged. However, it’s far from perfect. Sizable numbers of voters who tell pollsters they will “definitely” vote end up missing the election. These voters probably had the best of intentions to carry out their civic duty. But finding the time to vote got lost in the shuffle of busy lives with many competing priorities and activities.

Since asking voters about their intentions isn’t a sure thing, pollsters rely upon history and other clues for guidance. We know, for example, that younger voters always show up at a much lower rate than other segments of the electorate. History, though, while helpful, can only get us in the right ballpark.

For example, looking at the last four presidential elections reveals many different models of voter turnout. In 2004, nationwide, the number of Republicans turning out to vote equaled the number of Democrats. But in 2008, Democrats had a 7-percentage point advantage. Last time around, in 2016, the Democrats outnumbered Republicans by just 3-percentage points.

But how do you apply the lessons of that history in an unprecedented event like the pandemic we are enduring this year?

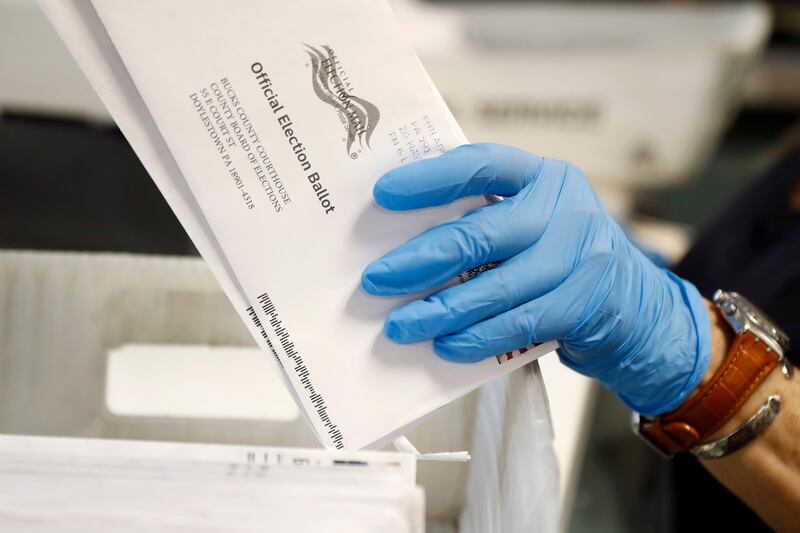

For example, my latest national polling shows that President Trump leads Joe Biden by 16 points among those who will vote in person. But Biden leads by about 50 points among those who will vote by mail. If we were to (mistakenly) assume that the number of ballots cast by mail would be similar to 2016, the president would easily be reelected.

But that’s not a credible model. For many reasons, we know that in the year of the pandemic the number of votes cast by mail will be much higher than ever before. The question is, by how much? Bluntly, there’s no way to know that answer today. We have absolutely no relevant history of getting out the vote in a pandemic.

What we do know today is Biden supporters are far more likely to say they will vote by mail but have never done so before. Biden voters are also more likely to say they don’t know how they’ll vote — by mail or in person. As a result, one of the big questions in election 2020 is whether such voters will vote at all. If they do, that would lead to a higher than expected turnout and be good news for Biden.

The bottom line is that while it’s always difficult for pollsters to determine who will show up and vote, this year will be even more difficult. That doesn’t mean the polls should be disregarded — but it does mean they’re a starting point for analysis rather than the final answer.

Scott Rasmussen is an American political analyst and digital media entrepreneur. He is the author of “The Sun is Still Rising: Politics Has Failed But America Will Not.”