The first slave schedule Sharon Leslie Morgan saw was in Alabama while researching her own family branch.

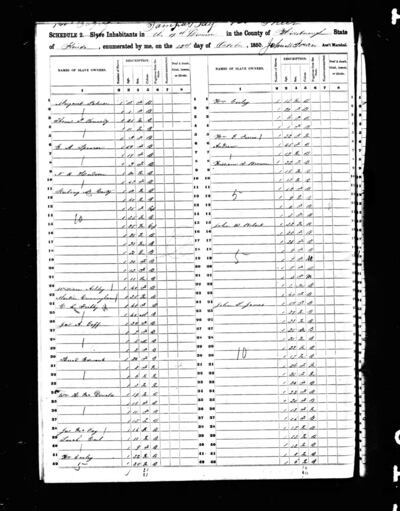

The only names belonged to the slave owners. Her family members were nothing more than a number. Ticks on a page.

She cried.

While many of us hope to encounter warm and friendly family stories when embarking on learning about our heritage, the reality for the majority of Black Americans is that their discoveries will be similar to Morgan’s: painful.

Slavery. Segregation. Lynchings. Mobs. People treated as property.

Morgan, who is a keynote speaker at RootsTech later this month, has helped countless African Americans discover their heritage. Though the journey to reclaiming those identities may be emotional, it is an important one that leads to healing.

This year’s theme for Black History Month is The Black Family: Representation, Identity and Diversity, and while talking to those who have dedicated their lives to preserving the stories of Black history and connecting the ties that bind, I found words of healing greatly outweighed the pain: Forgiveness. Fulfillment. Identity. Legacy. Pride.

Who we are is shaped by those that came before us. But what happens when we don’t know who that was? What is the responsibility of the posterity of those who inflicted such loss?

After my recent conversations I concluded that individuals today find themselves with a unique opportunity: Change the future by preserving the past.

The power of reclamation

I like to think of recorded history as a tapestry: You could remove threads from the cloth and still get a good picture, but it would lack substance and context. It’s often lopsided, biased and lacks the details and nuance that make it interesting.

Black History Month is largely about recovering those missing threads. It’s about identifying and celebrating the contributions of Black people all throughout history.

This month’s theme hones in on the importance of the Black family, a topic often neglected or forgotten in favor of the individual, and here the tapestry analogy works well. Missing threads in family history equates to missing threads in individual identities.

“When you don’t see yourself in history books, and you don’t see yourself on television, and you don’t see yourself in all the ways that people can see themselves? That is a problem,” Morgan told me. “It leaves a void inside of you.”

I spoke with Morgan over a video call. She’s lived all over the world but participated in our conversation from her home in Mississippi, where she now resides after first visiting to conduct research for a book she was writing on a branch of her father’s family.

Her journey is fascinating. Starting with a simple look into her family history, she became the founder of Our Black Ancestry, published a book on the topic and is the recipient of multiple accolades, including the James Dent Walker Award from the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society for her outstanding accomplishments for preserving African American history.

I asked what insight all her experience has given her about the value of looking back, despite the emotional toll that accompanies it.

“You will find these triumphs, this picture of resilience,” she said. “This picture that we are a very strong people. We have survived this long, and we really have to honor the people that came before us.”

Yes, there’s pain in tracing Black family history, but what I heard more of from those I talked to were the wins, the satisfaction of filling a hole you didn’t even realize was there.

Identity is as much a product of what we experience in our own lives as it is from what our ancestors pass down.

I spoke with Thom Reed, deputy chief genealogical officer for FamilySearch International, about his work to help reclaim African roots. He spends his days working with various organizations and professional partners to preserve the stories of those with African heritage around the world, but also has personal investment in the work.

Growing up, the label “African American” didn’t quite make sense to him. He couldn’t trace any sort of personal connection to Africa, so calling himself Black made more sense.

That changed when he had the opportunity to take a DNA test and learn specifically where his roots are based.

“For the first time in my life I felt, truly, a connection to my homeland in Africa,” he told me.

It hit home that his family story didn’t begin with “some random enslaved person that came to the United States,” but that he could still trace a direct line of descendants all the way back to Africa.

His eyes light up and his smile grows as he tells me about a picture he was able to take while on a work trip in Africa. They took a photo in one of the villages with everyone hugging. To Reed, it felt like coming home.

“I don’t know these people, I don’t speak their language.” He pauses, “But this is my family.”

A work to do

There are towns and cities all over the United States today that take pride in their heritage. Maybe you’ve even seen some of these local festivals celebrating Swiss, German or Swedish roots. Those origins go back more than a century, but the descendants are still happy to perpetuate traditions and claim heritage from these countries.

Many Black Americans don’t have that joy. Many genealogists refer to the “brick wall” of 1870 — the first census that counted African Americans as people with first and last names instead of as property. A tradition of oral history has also made it difficult to trace roots, and many records are not in collections but scattered in local courthouses.

Several organizations and experts around the world have cropped up, but very few house collections with a large number of records.

That’s part of what inspired the Reclaiming Our African Roots — or R.O.A.R — initiative that FamilySearch is spearheading, along with its growing list of partners. After noticing the interest in recovering this information, FamilySearch realized the potential power of working together.

“We want people to understand their heritage, we want people to understand their identity.” — Thom Reed

“We want people to understand their heritage, we want people to understand their identity,” Reed explained. “We want to make it, collectively, the opportunity for people to truly reclaim their African roots.”

The initiative is still in its infancy, but Reed has big plans. His hope is that eventually 80% of African Americans will be able to go to the database and make a family connection on the first try.

It’s a daunting goal that would have untold impact. Instead of spending years trying to trace roots, most Black individuals would be able to get their family history journey started with just one search.

Reed’s excitement is palpable and infectious. But this history has long been neglected, and I can’t help but feel that in some ways, it’s a race against the clock.

A great deal of records are in danger of being lost. The African Heritage team at FamilySearch has been diligently working to preserve these. They’ve made dozens of collections digitized and searchable, and have roughly 20 million records available right now.

It seems like a lot, but as Brent Hansen, the African Heritage program manager at FamilySearch, told me, it could be just the tip of the iceberg.

“There’s tens of millions probate records,” Hansen said. “But we don’t know how many records are in courthouses, how many are on plantations. These records are everywhere — and they’re also nowhere — because most of these are really small.”

Reed told me the goal of R.O.A.R is to digitize and compile somewhere between 250-500 million records. That’s an unheard of amount for one collection.

Tragically, many valuable sources are at risk of being lost.

A recent project in Houston to preserve the headstones of the Historic Evergreen Negro Cemetery is just an example. The cemetery had fallen into disrepair; overgrown trees, sinking headstones and neglect were taking their toll. If lost, descendants lose access to the important names and information recorded there.

That cemetery is one of an estimated 4,000 historic Black cemeteries across Texas. All of them are in critical need of saving. Only 10% of an estimated 4,000 headstones are legible in one Houston cemetery, Hansen said.

“The only way this work could happen because of how big it is,” he asserts, “it’s going to happen with the community.”

A responsibility for all

“I’m a white guy who recently discovered my ancestors were slave owners. What do I do?”

While hosting a Facebook Live event for Black History Month, Reed received one of the most common questions he hears. There’s a tendency to think of white and Black histories as separate, but many are surprised to find how entangled their histories are with those of Black families once they reach pre-1870.

The next step after uncovering that information, Reed says, is to share. Those bills of sale, those plantation inventories that may be hiding in someone’s attic — those are all valuable and important to descendants of the people on those documents.

“Tell everybody. Let people know so that those records get shared in any way you can,” Reed emphasized. “Use websites like Beyond Kin, or go and create your own blog, or go on Facebook and join Facebook groups and say, ‘I’ve got these records.’”

It’s a question similar to that which I, a half-Asian Canadian immigrant have asked myself. I believe these are stories worth saving, but what can — or should — the average person do to assist?

To Morgan, all Americans have a responsibility and investment in preserving Black history.

“For people to forgive, it requires some accountability,” she said. “American society needs to recognize the harm upon which it was built. It committed genocide on Native Americans and enslaved Africans. ... Somebody’s got to own up to that in order to achieve a state of peace with one another.”

Kayla Jackson, a marketing coordinator at FamilySearch, talked to me about the litany of Black History Month events the team has put together. The message they hope to relay is that Black history is for everyone.

“Black History Month is a learning opportunity for all people,” she said. “We want to highlight those stories to help people understand how Black narratives are interwoven and integrated into American history.”

Without the buy-in from communities and tech-savvy youths, the uphill battle will be even rockier.

The efforts made to reclaim this history cannot lie on the shoulders of Black communities alone. Black history is our history, and as such we ought to have a collective interest in preserving it for future generations, not just for the history books, but for the individual seeking answers and clues to their identity.

Those with African heritage looking to discover and preserve their histories, this year’s RootsTech is an invaluable resource. The conference will be held virtually for the first time, and more than 40 classes will focus on African heritage and genealogy.

Unlike previous years where one would have to attend in person, anyone with African heritage can tune in and find resources on how to begin their own journey and resources on where to start.

‘The end product of a long line’

This is about the Black family. Its past, present and future. The tense state of race relations today largely stems from a neglect and misunderstanding of this topic.

“One of the realizations I felt after with George Floyd is that ... people look to Black people as not having an identity. And therefore they become expendable,” Reed explained.

Black families exist — and they have always existed. Stories often focus on the individual, but African American families as a unit have made significant contributions to history. Throughout everything, they have persisted and survived. They have overcome tremendous struggles and managed to find ways to maintain connections, despite all that stood in their way.

“You are the end product of a long line of people that came before, and you are the beginning of a next line of people who will come after.” — Sharon Leslie Morgan

To forget that legacy is a disservice to all.

“You weren’t born in a cabbage patch. You weren’t delivered by a stork,” Morgan told me. “You are the end product of a long line of people that came before, and you are the beginning of a next line of people who will come after.”

To heal the generational trauma that afflicts an entire population, the ties that have been cut must be restored.

African Americans face unique and painful challenges in tracing their family lines: wounds that haven’t healed, apologies that are deserved but never made. But, as multiple people told me, we live in modern times. The sins of the father can be atoned for.

I ask myself what my role in all this is. I’m still figuring it out, but I think it starts here, with me. With sharing the stories of others, guiding those to the resources that will benefit them.

This is about the human narrative, and that is something I am invested in. Each small part of my own family story has given me a sense of identity, enlightenment on where I come from and where I’m going. I desire that all of humanity have that same sense of connection.

There is more to the story than pain and loss.

“You have a legacy,” Morgan assures, “And it is a strong one.”