In an age when a presidential candidate sells Bibles and members of Congress endorse Christian nationalism, it begs the question: What should be the relationship between religion and government? How should politicians bring their faith into their governmental positions? Is there a place for faith in governance? If so, what is it?

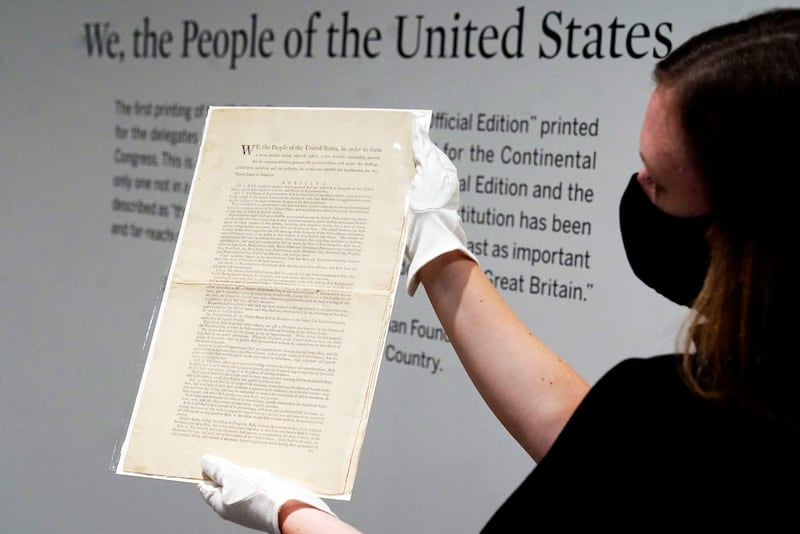

When I taught classes on the First Amendment, students often would tell me they knew that the Constitution stated that the United States was one nation under God. Or they would insist the Pledge of Allegiance was in the Constitution. Some would assert that the Constitution guaranteed that our nation was based on Christianity.

The Constitution does not say any of that. There is only one reference to religion in the original Constitution. That is the provision that no religious test can be used for federal office, meaning that no one can be denied a governmental office because of their religious views or affiliation. The only other reference is the First Amendment prohibition on an established religion (in other words, a state-sponsored religion) and a guarantee of the free exercise of religion. (Latter-day Saint history shows that religious freedom guarantee was not easy to enforce when a mob was raging.)

Why did the Framers of the Constitution say so little about religion in the nation’s primary founding document? It is not because the Framers were nonbelievers. Their writings and speeches suggest they believed in God, although in differing ways. Many attended church services. The vast majority were Protestants. So, why didn’t they use the power they had in writing the Constitution to give their own religious views preference in the new nation?

Generally, they considered religion to be a matter for the states and not the federal government. However, there was support as well for the notion that faith was a personal matter and that government should not be used for imposing religious beliefs or practices. The Framers’ views on religion were shaped by European governments’ treatment of people who did not subscribe to the established church, whether it was Catholicism in France or Spain, Lutheranism in parts of Germany, or Anglicanism in England. They remembered that the United States, as English colonies, were settled by pilgrims leaving Europe because they were persecuted there.

Early American leaders did not want to repeat the mistakes of the nations from which their ancestors fled. James Madison, the primary author of the Constitution, wrote that: “The purpose of separation of church and state is to keep forever from these shores the ceaseless strife that has soaked the soil of Europe in blood for centuries.”

Even though most were personally religious, they did not want religion to play any formal role in government. They wanted to be careful not to allow any religion to harness political power to further their cause. Thomas Jefferson expressed this view succinctly that government should not be used to support religion when he stated: “It does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are 20 gods, or no God.” Answering complaints that Christ was not mentioned in the Constitution, George Washington responded that “the path of true piety is so plain as to require but little political direction.”

Today, we have politicians who reject the Framers’ position that, although a politician may be personally faithful to a particular religious view, they should not use their political power to support a particular religious view or affiliation. They claim the United States should be a Christian nation and that government can be used to support Christian values. Some believe the First Amendment guarantee of freedom of religion applies only to Christians.

Politicians need not sublimate their faith while acting in their official duties. However, they also should not seek to use their power to impose religious beliefs or practices on others. There is a danger that the United States could turn back to those European nations where varying religious beliefs were not respected. Then, the Framers’ work in creating a nation where religious pluralism is cherished would be undone.

Richard Davis is the author of “Faith and Politics” (Deseret Book and the BYU Religious Studies Center, 2024).