I watched each survivor file in one after another. They sat at the front of the room, sitting in an order that clearly had some significance, but wasn’t obvious to the naive onlooker.

The woman and man in the middle had a special bond. She carefully pulled the seat out for him and during introductions, she reached over to adjust the collar on his shirt.

The wrinkles in her face were deep but her smile bright and eyes alert. He looked a little more distant but still present in the room.

She stood and started to sing, her voice clear and immediately filling the space in the room. With almost no delay, the other survivors started to sing with her, clapping in unison and beaming with the lyrics of a song that clearly had national importance, truly a profound sight when considering the tenuous relationship Tutsi genocide survivors have with their national identity as Rwandan.

Then when the singing stopped, she began to tell her story with the help of a translator. “I have nine siblings, and I am the mother of nine children, she said, and seven of them were killed during the genocide. I won’t tell you my whole story today, but I will tell you what choices I have made following the genocide.”

Suddenly it became clear who the man sitting next to her was not her husband, nor her brother, but the man who had killed her family during the genocide. She slowly sat down and exclaimed, “I have forgiven this man.”

The tension in the room was palpable. Other women who had traveled with me to Rwanda had also survived genocide. Many of them came from the front lines of the escalating genocide in Sudan. Others had lived through atrocities in Iran, South Africa, and Liberia. Many were crying, and you could see them replaying their own traumatic memories as the stories were shared. I turned to search the faces of the other women in the room, looking for some hint of whether they could accept this radical moment or if their own pain would give me permission to hold my own judgments.

With voice unshaken, she continued, “God helped me after the genocide and gave me a heart to forgive. Where there were tears and sadness, God replaced this with hope and power to help others. Forgiving heals, not just the person who forgives but the person you have forgiven.”

In that moment, each of us were confronted with a deep and harrowing choice, the words from a scripture of my faith running through my heart, “Judge not, and ye shall not be judged: condemn not, and ye shall not be condemned: forgive, and ye shall be forgiven.”

Clearly there were thousands of moments of earlier wrestle, pain, and anguish unseen both for this mother and for this man whom she had forgiven.

And no one in the room could ever understand the full scope of what she had experienced. But her invitation was resounding, and her example profound. I have forgiven this man.

Seemingly against all odds, against political divides, against misinformation, against extremist religious teachings, against history, against trauma; this woman chose to resist the legacy of violence and continues to choose the path of forgiveness every day.

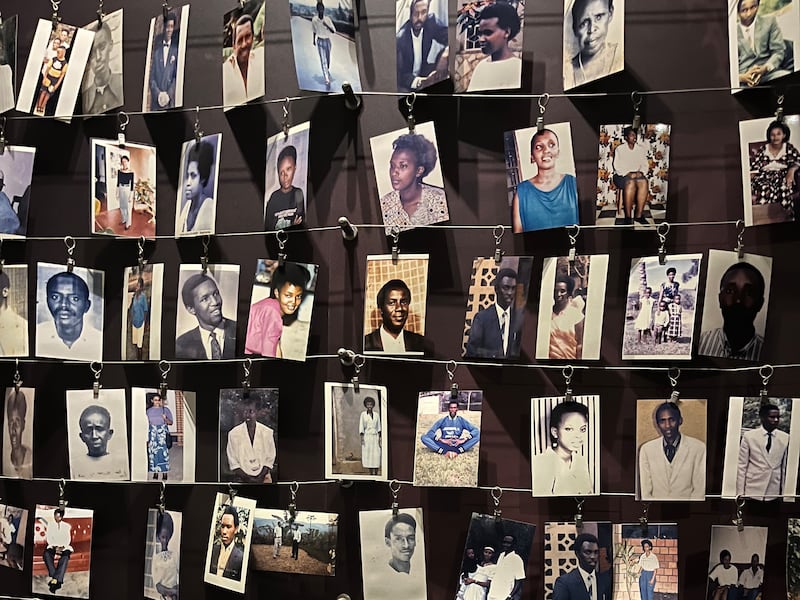

In April 2024, Rwanda commemorated thirty years since the genocide; a genocide which took well over a decade to orchestrate and just one hundred days to execute. Over 800,000 people were brutally murdered. In the aftermath of the genocide, local communities created their own courts, called “Gacaca,” to hold perpetrators accountable. The word Gacaca refers to the short grass where the village chiefs would meet to resolve differences and heal grievances. Through these justice efforts, at least 1.2 million cases of genocide were heard and processed. And now, decades after the events that shocked the world, there are people who choose forgiveness every single day.

It was an interesting dichotomy to be in Rwanda on the day of the US presidential election. When I told one survivor about my work to disrupt the cycle of genocide, she asked me if there would be genocide in the United States. My answer was a definitive no, but acknowledged harsh and even violent rhetoric in the U.S. continued to grow. Phrases like targeting the “enemy within” were used to divide Rwanda leading up to the genocide and have been seen more and more in US political debate.

Shockingly, Holocaust denial continues to grow in the United States. Failure to acknowledge ongoing atrocities in Palestine persists. And current events in Sudan rarely if ever make the news cycle even though estimates are that as many as 150,000 women, children, and men have been killed in connection with the years-long civil war (a figure that includes starvation and infection disease deaths incident to the conflict, along with violent deaths).

This is not just about a single country; it is ultimately about how we confront ideas that lead to genocide ideology. One prosecutor of the Nuremberg trials explained it this way, “Most genocides are committed in presumed defense of some particular ideal; whether it be religion, ideology, race, self-determination, or nationalism. These are the things that usually motivate people to go out and kill and prepare to be killed. They justify it as necessary to protect their own conception of what the world should be like. It is important to understand that point. These are not wild, raving maniacs.”

“You cannot kill an idea with a gun; you can only change it by a better idea.”

Each of us can learn from Rwanda and play a critical role in global efforts to end genocide. Even in the United States and countries where conflict may be far out of sight and out of mind, every American has a role to play in challenging violent ideology including by practicing forgiveness and promoting human dignity.

Inspiration to overcome our own political divides can be found in the powerful example of justice and reconciliation in Rwanda. We need local efforts to bring our communities together and efforts to challenge rhetoric designed to tear us apart. The true “enemy within” is our own apathy to ignore the consequences of failing to confront the hate and discrimination that can set the stage for deadlier outcomes in our own beloved country and in the world.