Nnachi Azuewah didn’t intend to stay in the United States. A brother-in-law to the first President of Nigeria, Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, Nnachi always planned to finish college and return to his hometown. But an unexpected military coup and ensuing turbulence led him to stay in the United States where he met his wife and had three children.

While he was establishing himself in his new country, he was impressed with the missionaries of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in white shirts and name tags he saw walking around, started talking to them and eventually converted.

Now, years later, he is the president of the Elder’s Quorum of the New Carrollton Ward just outside of Washington, D.C. He introduced his cousin, nephew and father to the faith and has served as a core member of a growing Latter-day Saint West African community in the D.C. area.

Worship services are conducted in various global languages in his congregation, and Nnachi says having someone to talk to at church in their own indigenous African language makes worship easier for new Latter-day Saint immigrants from the same area.

His story is not unique. Immigration and religious communities have been intertwined since the puritans landed in New England. Since then, immigration has diversified the religious landscape away from the white Protestantism and indigenous faiths that defined early America, a trend that has continued up to the present.

But a clear-eyed view of how immigration impacts faith benefits from a grounding in real data, which can correct mistaken perceptions while confirming truthful ones.

Immigrants aren’t making America more religious

One especially large misperception that immigrants are making the U.S more religious comes from highly visible cases of refugees from the more religious developing world or that Mexico is a highly religious country (even though, according to Pew, Mexico is less religious than the United States).

However, when we look at data from the Cooperative Election Study and the Pew Religious Landscape Survey, immigrants do not appear to be significantly more or less religious than non-immigrants in the United States. For example, they attend religious services about as much.

But maybe immigrants are more likely to, say, believe in God or the afterlife even if they are just as likely to go to church? There is also little evidence for a significant difference between immigrants and U.S. born individuals according to the latest wave of Pew data.

When participants were asked if they believe in God or a universal spirit, 15% of immigrants did not and 16% for those with both parents born in the U.S. When asked if they believe people have a soul or spirit and a physical body, 15% of immigrants say they don’t and 12% of respondents with two parents born in the U.S. said they don’t.

That difference is minimal. There is little data-driven support from this latest survey for the idea that immigration will help refill American pews.

But why is that? Could people just be losing faith when they immigrate to the U.S.?

Thankfully, Pew asked not only asked questions about people’s current religious practice but whether they attended religious services while growing up. We don’t know which country they were living when they were “growing up,” but, if there were waves of immigrants moving from more religious areas of the world to less religious, we’d see some of that in the data.

Here, the story of the hyper-religious immigrant is turned on its head. People born outside of the U.S. attended religious services less during their childhood than those born in the United States.

So, while immigrants will put more people in pews simply by being in America, their influx probably won’t increase the proportion of Americans who are religious.

Immigrants are increasing ethnic diversity of American faith

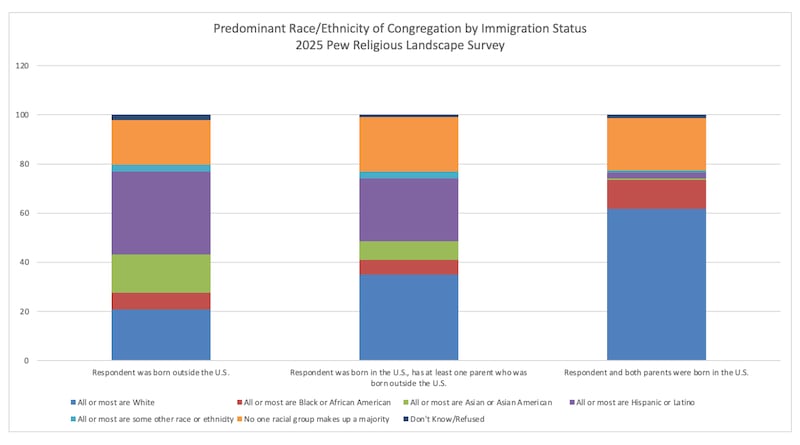

While immigration might not significantly change how religious America is, it changes what religion looks like. Here there are huge differences. Unsurprisingly, the religious experience of immigrants looks very different. While only about 1 in 5 immigrants who attend services have predominantly white congregations, for those whose parents were born in the U.S. it is about 3 in 5.

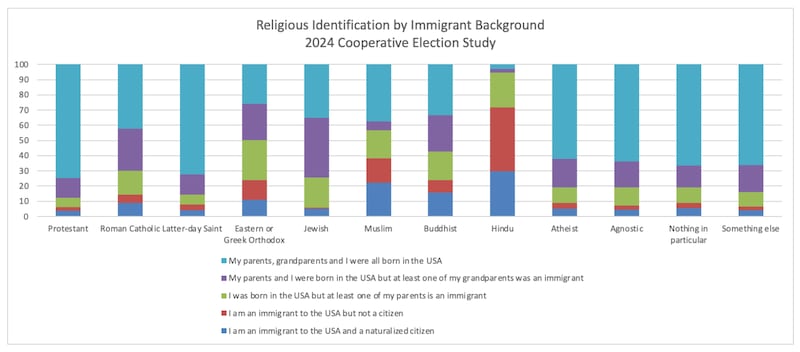

It’s clear from the Cooperative Election Study that some religious traditions are more immigrant heavy than others; immigration clearly adds diversity to the American religious tapestry theologically as well as racially. So much so, in fact, that most Jews, Buddhists, Muslims and Hindus have at least one grandparent who was born outside the United States, and most Hindus in particular are immigrants themselves.

Changing American Islam

Because of immigration, Hinduism and Islam have been exploding in America. From 2010 to 2020 Hindus in North America grew 50% according to Pew, largely driven by South Asian immigration. According to one Pew projection, Islam will be the second largest religious group in the U.S. by 2040, with about 1 in 50 Americans predicted to be Muslim by 2050.

The Muslim community (of which about 4 in 10 in the United States are immigrants) is no stranger to using their faith to provide a ballast, help and sometimes balm for refugees from war-torn, often Middle Eastern, countries.

In a totally new, discombobulating environment, Islam helps adherents who are immigrants connect with what they know. Often the first stop of Muslim refugees when they reach the United States is their local mosque, and they become de facto shelters and community centers that provide food and basic services to refugees, many from the same countries of the Muslim leaders.

“In our culture, you can’t deny the people who come to the mosque,” said Imam Omar Niass, who runs a mosque in the Bronx, The Associated Press reported. “We keep receiving the people because they have nowhere to go. If they come, they stay. We do what we can to feed them, to help them.”

Similar to Catholicism, Islam in America is experiencing significant demographic changes from immigration. According to this same survey, 56% of Muslims who were born in America are Suuni, with 10% Shi’ite, the branch represented by places like Iraq and Iran. One-fifth are also from the Nation of Islam, the New Religious Movement founded in the U.S. in the early 20th century. Immigrant Muslims, on the other hand, are 90% Suuni, while under 1% are Nation of Islam.

Changing American Catholicism

Even more established faiths are changing in connection with immigration to the U.S. While Catholicism in America was largely founded on the backs of early British Catholics (Lord Baltimore) and Irish and Italian immigrants, Hispanic — and, to a lesser extent, Vietnamese — immigration has changed the Catholic landscape once again.

As highly Catholic states such as Maryland and Massachusetts have seen disaffection and population declines, more vibrant Catholic communities in the South and West, buttressed by large inflows from Hispanic immigration, have risen up to take their place as the centers of Catholicism in America. Now, about a third of all U.S. Catholics are Hispanic, according to Pew.

Fielding a large survey to their different dioceses in late 2024, the U.S. Catholic church found that about a quarter of all parishes now offer Mass in Spanish, and about 45% have some kind of Hispanic presence or ministry.

But Hispanic immigration is only part of the Catholic immigration story, as 78% of ethnically Asian Catholics in the U.S. are immigrants, largely from countries like Vietnam, and in 2022 about 4% of seminarians about to be ordained to the Catholic priesthood were born in Vietnam.

As confirmed by the Cooperative Election Study, Catholicism is a very immigrant-heavy faith, with a majority having at least one immigrant grandparent. However, other faiths are even more immigrant-heavy.

Changing American Buddhism

According to this same survey, about a quarter of people of Vietnamese heritage in the U.S. are Buddhist, a quarter are Catholic and 40% are religious “None.” So, the Vietnamese story in America is a Buddhist one as well.

A little over 40% of American Buddhists are either an immigrant or have a parent who is an immigrant. Chùa Quang Minh, Georgia’s oldest Buddhist temple, is a testament to this. Founded by Vietnamese refugees who fled the communist regime, the temple afforded a sense of community and stability for refugees who, in some cases, had lost everything.

According to Lam Ngo, the president of the temple board, “Some people have lost their whole family, all their dear ones, their home, their brothers and siblings … Or imagine you spend your youth in a reeducation camp, and you work like a slave.”

Interfaith support for immigrants

This religious assistance often crosses devotional lines. While historically the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society was formed to help Jewish immigrants get on their feet, now it helps immigrants of other faith traditions as well. In the wake of Afghanistan falling to the Taliban, tens of thousands of Afghans hurriedly fled Kabul with sometimes little else but the clothes on their back. The Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society held a call with almost 300 synagogues hoping to find communities who would be willing to help “adopt” Afghan families and help them get on their feet.

Similarly, through its JustServe initiatives, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have been involved in refugee resettlement assistants across the country. For example, Deseret Industries provides apparel and other necessities, while Latter-day Saints staff an immigrant “welcome center” that provides aid to immigrants coming across the U.S.-Mexican border.

Less dramatically, a faith can help refugees feel more at home in the new, sometimes foreign surroundings, from Muslim immigrants celebrating Iftars in America (the traditional communal meal after breaking the Ramadan fast) to Indians making Diwali, a Hindu festival, a family tradition in their new land.

Moving to another country can make immigrants appreciate their faith even more strongly than in their previous home, where it can be easier to take for granted, with one classic sociology paper suggesting that the increase in belief in an afterlife in the U.S. during the 20th century was largely due to Catholic and Jewish immigrants’ children returning more strongly to their native faiths in America.

Even in cases where faith is not immigrant-heavy, a religious community can help. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is not an immigrant-heavy faith, relatively speaking; 14% are either immigrants or have a parent who is, compared with 30% of Catholics and half of Eastern Orthodox. (In 1850 and 1860, Utah was one of the most immigrant-heavy areas in the country, but Latter-day Saints since that time have been encouraged to stay in their home countries).

Even so, there exists a diversity of Latter-day Saint congregations. In the D.C. area where Nnachi Azuewah resides, there are congregations catering specifically to French speakers (largely from Francophone Africa), American Sign Language, Chinese, Persian and Spanish.

From Nigerian elders in suburban wards to Vietnamese Buddhists in Georgia, immigration is weaving new threads into an ever-growing religious tapestry. Azuewah’s ward looks different than it would have a generation ago. And in that way, it’s a microcosm of America as a whole: same faith, new faces and a story still being written.