People hear rumors of a new technology that stands to destroy the next generation’s livelihood. Fears spread that the work and lifestyle they enjoyed may not be there for their children and grandchildren ... that new ideas will destroy the moral fabric of society ... that opportunity is shrinking, and there is little hope for future prosperity.

But this scenario isn’t 2025; it’s the 1750s when the Industrial Revolution spread across Europe. Everyday people feared that it would destroy their livelihoods, culture and morality.

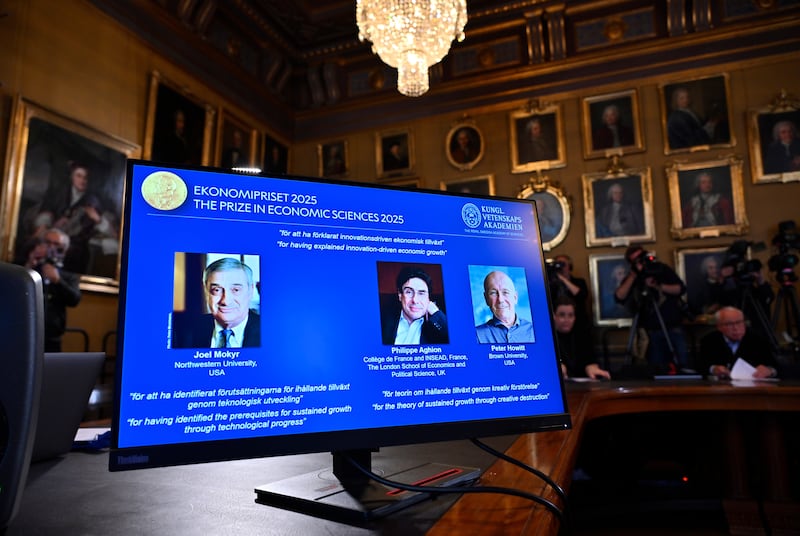

How innovation created new challenges and opportunities from that period is the focus of the 2025 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences awarded by the Swedish Riksbank.

The three prize winners this fall devoted their careers to understanding that explosion of economic growth that followed industrialization and how humanity can harness innovation for continued improvement. Northwestern University’s Joel Mokyr received half the prize, while Philippe Aghion (Collège de France and London School of Economics) and Peter Howitt (Brown University) shared the other half.

In a world of artificial intelligence poised to make work obsolete, deep fake videos that confuse truth and make immoral material readily available in our homes, or biomedical engineering with its bewildering ethics, it is easy to feel like the world is unmoored from a previously secure harbor.

The prize winners’ research provides a hopeful lesson to those worried about future as our economy once again is disrupted by new technologies and innovations that can be unsettling.

This announcement marks the fourth Nobel Prize in a row to spotlight economic history — the study of how markets, technology and institutions shaped the past. Mokyr’s work has long focused on what fueled the innovation boom of the Industrial Revolution.

Knowledge, he argues, is the ultimate public good. Public goods have two important qualities: you cannot block others from using the good and when one person splits the good, it doesn’t reduce the value of it for others.

Once someone invents a new idea, others can easily learn from it and apply it to their own circumstances. Unlike a pizza or a Snickers bar, an idea doesn’t get “used up,” but is instead free for all to use as many times as they like. My middle schooler learning the quadratic formula doesn’t cause me to forget it.

But because others can copy new ideas freely, private inventors have little incentive to create new ideas on their own. Thus, research and development are rife with the free rider problem. Economic growth therefore depends on a public sector that protects patents and rewards innovation.

Governments, however, have one major flaw: a lack of perfect information about what is coming. Bureaucrats and elected officials can’t predict which technologies will succeed. Rather than trying to pick winners, they must foster what Mokyr calls a “culture of growth.”

A growth culture depends on the right kind of innovation — applied knowledge that escapes the confines of monasteries, laboratories, and universities and benefits everyone in the “real world.” The most powerful innovations rapidly develop applications into the workplace, field, or classroom.

When educated farmers, engineers, and entrepreneurs apply new technologies, they bridge what Mokyr describes as “propositional” and “prescriptive” knowledge — the link between discovery and use.

During the Industrial Revolution, Europe’s thinkers, inventors and builders created such ecosystems: French salons, Italian inventors, British factories. In America, those same forces thrived under a system of constitutional republicanism, accelerating growth even further.

Even during the bloody conflicts of Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln set aside federal lands for states to sell and establish land grant colleges. Each state now has a public university whose mission is to create the culture of growth that spins off new applied technology for the benefit of all.

But innovation doesn’t move in a straight line. Aghion and Howitt built on Joseph Schumpeter’s idea of “creative destruction,” exploring how new technologies create progress while rendering old ones obsolete. Innovation, they remind us, burns through industries like a forest fire — destroying, while also clearing space for new growth.

Not everyone benefits immediately. Legend has it that 18th-century French and Dutch mill workers threw their wooden shoes — sabots — into the gears of new machines to protest losing their jobs. From that act, the word “sabotage" entered our lexicon.

These transitions can unsettle workers and tempt politicians to promise a return to a “simpler” past through populist movements. Yet such nostalgia will result in slower economic growth and a reduced standard of living for all.

As the chair of Nobel Prize committee stated when announcing the new laureates, “the laureates’ work shows that economic growth cannot be taken for granted. We must uphold the mechanisms that underlie creative destruction, so that we do not fall back into stagnation.”

To sustain innovation, public policy must cushion short-term pain without stifling long-term growth. That means supporting science, funding practical research at universities, and maintaining faith in the institutions that enable discovery.

As we face new frontiers — artificial intelligence, quantum computing, biotechnology — we should remember the optimism of this year’s Nobel laureates.

Humanity has confronted such crossroads before. Each time, courage, curiosity and a belief in progress lit the way forward.