What does it mean to “stand athwart history yelling stop”?

Those were the famous words of William F. Buckley Jr., explaining the role of conservatives in culture and the mission of National Review, the magazine he founded.

It is one thing to yell stop. It is quite another, though, to turn back the clock. But that is what a certain segment of thinkers on today’s political right would like.

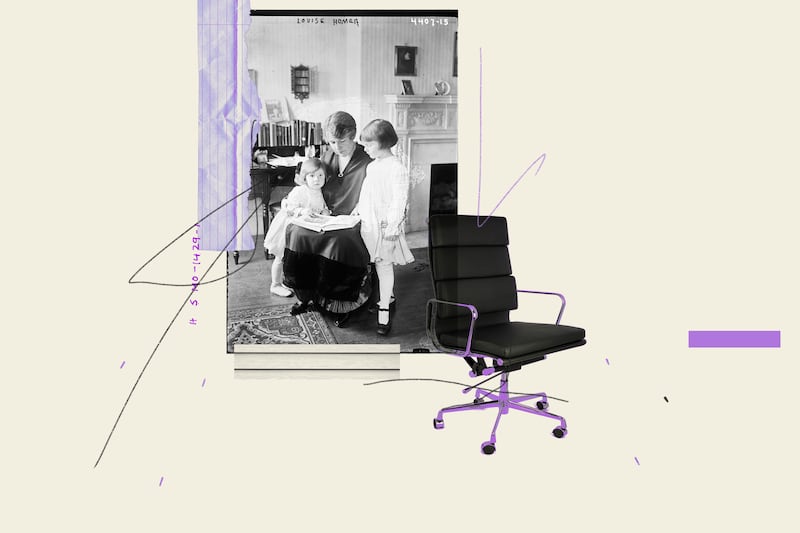

The impulse seems to be driven by nostalgia for a time somewhere in the middle of the last century, a time when people got married young, middle-class men were primarily the breadwinners, women could devote their time to raising children and keeping house, and everyone wanted to have at least a few kids.

Proponents of this lifestyle post pictures of mid-century kitchens on social media with the tagline “This is what they took from you.” Who is they? Capitalists? Globalists? Feminists? Some combination, no doubt. Meanwhile, there is little acknowledgement of what has been gained by humanity since you lost your avocado kitchen with the formica countertop, linoleum floor and the plate of cookies on the table.

The way to bring this back, this faction initially argued, was through government programs. There should be more paid maternity leave, larger child tax credits and maybe even baby bonds (of the kind the president recently announced and Michael Dell funded) in order to make family life more affordable. At the very least, these proponents argued, we should stop penalizing women by subsidizing day care but not subsidizing women who stay at home and care for their children themselves.

None of these policies were particularly objectionable, but money does not seem to affect family formation in the way that people would like to think. The wealthiest people often have the fewest children. And the wealthiest countries have the lowest birth rates. And places like Hungary, which were the shining examples of success, have seen their birth rates decline too.

As people like my colleague Tim Carney have written, there are other cultural factors that drive such decisions. The pressure to helicopter parent, for instance, or send your kids to expensive colleges or to pay for travel sports teams probably does more to reduce the birth rate than the level of the tax credit. Which is not to say there aren’t policies that could help. School choice might go a long way toward encouraging family formation. If you don’t have to afford a home in the most expensive school district in order to get your kid a decent education, that changes the calculation about when to start having children and how many to have.

While they have disagreed about how to encourage young people to marry and form nuclear families, conservatives have consistently made the argument that doing so is not only beneficial to society, it also makes people — and women in particular — happier. But now there is a faction that is not satisfied with simply trying to tinker around the edges of tax policy or change the cultural perception of family life, or to persuade women that lives focused solely or even mostly on careers do not necessarily lead to fulfillment. Instead, they want the government involved in trying to undo the sexual revolution.

I reviewed Scott Yenor’s book “The Recovery of Family Life” a few years ago. As I wrote then, “Yenor does not believe that biology alone explains everything or that our choices should be limited to only those that seem to come naturally to us. Rather, he argues that biology provides human life with ‘grooves’ and that the more we force people to ignore those, the harder things become.” This is exactly right, and there is a long tradition of conservative thinkers like Midge Decter and Kay Hymowitz who have argued the same thing for decades.

But Yenor has moved into the world of public policy, recently joining the Heritage Foundation. And his solutions to these problems — which I confess I glossed over in my review —are now being floated in Washington.

Yenor has, for instance, argued for the right of businesses to hire male head of households over other candidates for jobs. And while he has not quite called for more restrictions on contraception, he has suggested to the secretary of Health and Human Services to look into them more closely. Given that RFK Jr. takes an activist approach to the approval of pharmaceuticals, such a suggestion could have serious consequences.

Leaving aside that problem, and the obvious illegality of employment discrimination that my colleague Henry Olsen recently pointed out, the question is what sort of approach should conservatives take when it comes to the past?

On the one hand, there are important things about the past that were better for us. On the other hand, upending our lives (especially with government intervention) would cause chaos and harm to people who have built their existence on the structures that are currently in place. Conservatives, it was once thought, should be conservative in their temperament and their approach to policy too. We are not prone to revolution. But that answer is no longer satisfying. Now part of the new right wants to stand athwart history yelling “rewind.” Count me out.