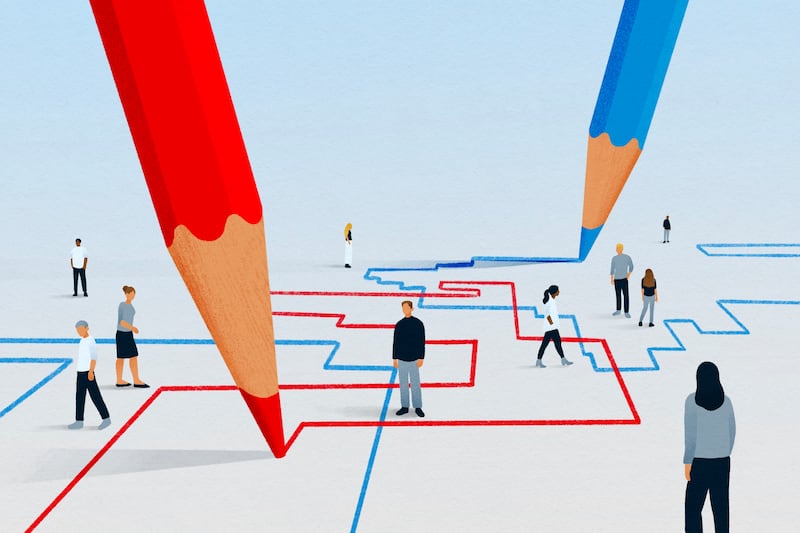

Across the country, redistricting has devolved into an overt political power struggle. What should be a once-a-decade adjustment based on population growth has become a partisan competition to lock in power, deepening political divides.

Utah is no exception. By securing one completely safe Democrat seat in a heavily Republican state, mapmakers pushed the remaining districts into extreme GOP margins that would normally be unthinkable. The consequences are far more serious than most people realize.

Safe seats don’t just determine which party controls Congress. They create echo chambers that fuel polarization. They reward extremism, punish consensus builders, and make Congress too fractured to enact sustainable solutions. By further polarizing Congress, the branch meant to speak for “we the people,” safe seats threaten self-government.

For Congress to pass laws that speak for the people, hundreds of members must find consensus on policies that can outlast the next election. Long-term solutions require broad consensus, and broad consensus requires honest engagement with competing perspectives.

Today’s political incentives make that difficult. Manipulated by conflict entrepreneurs, Americans increasingly reward outrage on Election Day. But angry politicians who torch their colleagues on cable news cannot govern with them. The behaviors voters increasingly reward create ineffective leaders, turning Congress into a performative arena instead of a legislative body.

Safe districts make polarization worse. Because candidates and voters speak almost exclusively to their own side, opinions harden and empathy weakens. This well-documented dynamic — the group polarization effect — pushes even reasonable people toward extreme views. Like-minded voters reinforce one another, rewarding candidates for sharper rhetoric and rigid positions. Dissent becomes rare. Rage bait replaces solutions. A constant barrage of false choices convinces Americans that we’re too divided to solve problems. People stop engaging with opponents. And that’s what truly fractures self-government. It’s not disagreement. It’s the refusal to engage all sides. That refusal unravels the collective wisdom that government by the people depends on.

When Congress cannot build enough consensus to solve serious problems, self-government is threatened at its constitutional core. Only Congress is authorized to make law. When polarization paralyzes Congress, the executive and judicial branches fill the vacuum — regardless of which party is in power — eroding the promise of government by the people. Courts are too insulated to represent “we the people,” and the executive is inherently one-sided. When Congress is weakened by polarization, each change in White House control brings costly, destabilizing policy whiplash.

It’s Congress’s job to reconcile the vast range of American views into solutions that can outlive the next election. In a highly polarized environment, Congress can’t do that.

If we want better outcomes, we must encourage the forces that produce them. Two stand out: competition and cooperation. Competition pushes leaders to improve ideas. Cooperation allows solutions to endure because they’re grounded in broad agreement. Safe seats encourage neither. With victory guaranteed, there’s no pressure to innovate and no permission to collaborate.

So what now?

In a state as red as Utah, there’s no way to make every seat competitive. But if we’re serious about preserving self-government, we need as many competitive districts as the math allows.

Will “we the people” speak out against systems that drive division? Or do we prefer polarization? Have we become so accustomed to algorithm-fed anger that we’ve lost the patience to forge agreement? Would we rather force our will than preserve the principles of government by the people that our Constitution was designed to protect?

Most Americans would never call themselves authoritarian. But if we’re honest, many of us recognize a growing impulse to impose rather than persuade, to prevail rather than understand. Whenever fear takes root, the human instinct is to assert control. But that impulse is fundamentally at odds with government by the people. Our Constitution’s foundational principles call on us to quiet that instinct within ourselves.

Self-government begins with citizens willing to quiet the urge to control, listen with curiosity, value various perspectives and work past the false choices inundating us. Systems can either reinforce or undermine those habits. Eliminating the structural echo chambers created by safe seats is one concrete way to support the habits of fellowship that self-government requires.

The country doesn’t need more safe seats. It needs more leaders — and more citizens — willing to listen, learn and build together. And it needs a Congress capable of doing its job.