The lifestyle phrase of the decade is how each of us can “have it all” — the family life, the fulfilling career, and a sparkling social and personal life.

Yet while some people try to “have it all,” a growing number of people, especially young men, are choosing the “none of the above” box paradoxically when they are in their prime.

No family, no job, no school. The proverbial guy in his 20s sitting in his mother’s basement playing video games is a reality for a not-insignificant number of men.

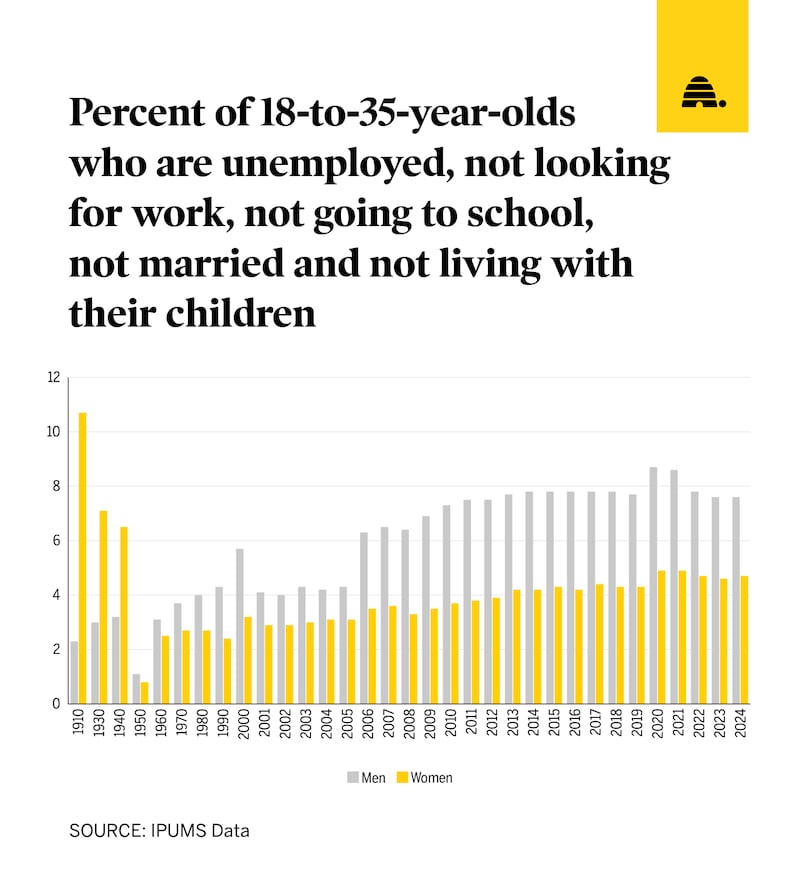

How common is it? If we look at the American Community Survey and Decennial Censuses run by the U.S. Census and processed by the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series out of the University of Minnesota, we can see how many people from 18-35 are (1) not going to school, (2) not working or looking for work, (3) never married, and (4) not living with children of their own.

This is a fairly low bar. For example, it does not include, say, a 30-year-old single man working a few shifts at the local Starbucks per week, or an unemployed, married man without child care responsibilities who sits at home all day.

A recent Washington Post article referred to the phenomenon of “stay-at-home sons.” In my own analysis, about 8% of 18 to 35-year-old men land in the checked-out category without enduring commitments to either school, work, spouse or children.

The stereotype is that it is the guy who has checked out, but is this true? Statistically, this does appear to be mostly a guy thing. But it wasn’t always that way.

There were more women without occupational commitments pre-World War II when women had fewer educational and career opportunities. But since World War II, the gender gap has flipped, with many more men than women simply staying at home without child care responsibilities.

The number of men “checking out” (as measured by these four data points) was increasing until 2014, and has remained constant at about 8% of men since then, with the exception of a bump during the COVID years.

It’s worth noting that this is not just an American phenomenon. In Japan, it is so common they have a special term (Hikikomori) for people who have voluntarily checked out of society altogether, often living with parents or simply alone in an apartment and rarely if ever venturing out. One government survey suggests that about 1.5 million Japanese, or 2% of 15 to 64-year-olds fit in this category.

One stereotype is that these young men are largely living in their mother’s basement playing video games and watching pornography. Is there some truth to that?

For video games, yes. One often-cited 2021 study that used time-use data suggests that much of the surge in male work dropout is directly related to video games becoming better and more appealing. Specifically, they calculated that “innovations to gaming/recreational computing since 2004 explain on the order of half the increase in leisure for younger men” and that about 38-79% of the decline in working hours relative to older men is due to video and computer games.

Furthermore, a recent report out of the University of Tennessee shows that 76% of young “NEET men” (a term used by economists that stands for “not in employment or education”) live with their parents. This is how they manage to survive without working. So, there’s something to the “living in parents’ basement” trope.

When it comes to pornography, although men who look at sexually explicit media often state that they also want to get married, frequent watchers are, in fact, less likely to actually get married.

After all, these lifestyle choices about free time, education, employment and marriage all run together. Married men are more likely to be employed and educated, and educated men are more likely to be married.

When screentime is taken as one category, the results are telling: non-working men spend nearly 2,000 hours a year “watching and playing on screens” — which a little math will show is the same as a full-time job. That’s right, men are literally dropping out of the work force to watch television and play computer games all day.

Still, some might wonder: Does it really matter if men decide to check out for a while?

Yes, in the most profound, existential way.

U.S. society is now not producing nearly enough children to replace itself. While some of this is because people prefer smaller families, the fact is that women want to have more children than they are having. On average, U.S. women would like slightly more than two children — which is just above replacement level.

But these same women are saying that one of the major impediments to having the family they want is the lack of eligible men as partners. In one survey, a majority of childless women who wanted children cited lack of a suitable partner as the reason for not having the children they want.

This disconnect isn’t just a personal failure of ambition; it’s a structural one. As Richard Reeves, president of the American Institute for Boys and Men, recently noted, the traditional pathway towards adult meaning is getting lost as core institutions such as religion, family and societal responsibilities have eroded. When these traditional “on-ramps” to adulthood disappear, many men simply stall out.

But in a soft defense of such men, secular society has not exactly done a great job convincing young men why they shouldn’t live lives of pleasurable, stress-free leisure. Traditionally, institutions such as religion gave men reasons why they should get up in the morning, put in that job application and create, raise and provide for a family, but with the decline of faith, there is increasingly no solid response to the question of “why not.”

While religious people are still largely getting married and having children, their secular counterparts are less likely to start a family that was once considered a milestone of adulthood.

It is true that in some sectors the kind of no-degree required, stable job with benefits has disappeared. But before people blame modern economics, my graph confirms that the number of life dropouts during the Great Depression was a fraction of what it is today. Indeed, in many ways, having the option of simply not doing anything is a wage of relative abundance in society, suggesting there may perhaps be some truth to the popular adage from G. Michael Hopf’s novel “Those Who Remain” that “Hard times create strong men. Strong men create good times. Good times create weak men. And, weak men create hard times.”

Men are increasingly simply dropping out while largely living off the largess of relatives or others while not contributing to the future.

Something has to give.

That’s not to say that all or even more unmarried men fit in this category, but when about one out of 10 men have dropped out completely, and many more women than men are attending college, it tangibly affects the overall supply and demand of the marriage market and the downstream marital prospects of women who want to be equally yoked to a partner.

Over a decade ago, journalist Kay Hymowitz’s article “Where Have the Good Men Gone?” struck a nerve with a new generation of women who were increasingly recognizing the Peter Pan attitude of the guys they were dating. Since then even more of the good men have gone away. That is not to say that young women aren’t going through their own problems, but when a significant chunk of young men check out from what makes life most meaningful, the very foundation of society starts to fracture.

But the ancient wisdom from a Nazarene carpenter still holds true. The man who tries to save his life for himself will inevitably lose it. It is only by “losing” himself that finally gives him the traction to move forward.