We are now approaching the 250th anniversary of our national independence, the near miraculous fruit of what George Washington referred to as the Glorious Cause of the Revolution. That anniversary will lead the country to other events worth commemorating, culminating in the “miracle at Philadelphia” and the ratification of the Constitution of the United States. As Thomas Jefferson’s first appointee to the Supreme Court, William Johnson, stated in 1823: “In the Constitution of the United States, the most wonderful instrument drawn by the hand of man, there is a comprehension and precision that is unparalleled; and I can truly say that, after spending my life in studying it, I still daily find in it some new excellence.” We will honor the names, thoughts, and actions of Washington, Franklin, Hamilton, Madison, Jefferson and Adams — a remarkable generation of pro-Constitution, or Federalist, statesmen who shouldered the lion’s share of responsibility, and have received the accompanying glory, for the nation’s constitutional design.

The Constitution had its original skeptics — “men of little faith,” as one scholar dubbed them — who opposed the adoption of the Constitution in the ratification struggle of 1787-88. The pro-ratification party referred to them as “Anti-Federalists.” The drama of the American founding requires an understanding of the indispensable role played by the arguments of these Anti-Federalists. Brutus, Centinel, the Federal Farmer, Agrippa, Cato and A [Maryland] Farmer were some of their pen names; they included prominent statesmen such as George Mason, Luther Martin, Richard Henry Lee, James Monroe and Patrick Henry — all of them champions of a negative and losing cause.

What divided the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists? As Herbert Storing argues in his seven-volume “The Complete Anti-Federalist,” their differences were those “within the family, as it were, of men agreed that the purpose of government is the regulation and thereby the protection of individual rights and that the best instrument for this purpose is some form of limited, republican government.” As we know, however, differences with the family are nonetheless real and often significant. What, then, were the Anti-Federalists for that inclined them against the Constitution?

What did the Anti-Federalists stand for?

In the first place, they stood for federalism, understood as the primacy and equality of the states, as opposed to what they saw as the consolidating nature of the Constitution. To the Anti-Federalists, the Constitution would so subordinate the states to the national government as to destroy them. As Storing notes, the Anti-Federalists were the conservatives in the debate, defending the status quo embodied in the structural principles of the Articles of Confederation. Indeed, the Anti-Federalists went so far as to accuse the Federalists of abandoning the principles of the Revolution when they jettisoned the doctrine of pure federalism.

The gravamen of this charge comes into focus when it is seen in light of the Anti-Federalists’ view that “there was an inherent connection between the states and the preservation of individual liberty” (Storing). As with the inherited republican tradition, the Anti-Federalists argued that free popular government could succeed only when exercised over a relatively small territory and homogeneous population. This argument for keeping primary governing power in the small republic — the state — rested on three considerations.

First, a small republic allows for a voluntary attachment of the people to their government and a voluntary obedience to the laws. In a small republic, the people can be familiar with those who govern them and are amenable to the persuasion that accompanies respect. The alternative was government by force, the rigid rule of a large and varied territory and population through military force or, as Storing suggests, bureaucracy.

The Anti-Federalists maintained that the central question of the proposed national government was not the organization of the government’s powers, as important as that issue was, but the extent of the powers themselves.

Second, it is only in a small republic that a genuine responsibility of the government to the people can be achieved. Short terms of office, frequent rotation and numerous representation ensure a likeness between the representative body and the citizenry, upon which an accountable and dependent representative body rests. In a large republic, the government envisioned by the Constitution inevitably would be unrepresentative and aristocratic.

Finally, only a small republic can foster the kind of citizen who is capable of maintaining republican institutions. Self-government depends on civic virtue, understood as a devotion to one’s fellow citizens and a deep attachment to one’s country, together with a willingness to subordinate private interest to the public good when the two conflict.

Such a citizenry presupposes homogeneity. “Brutus” argued, “In a republic, the manners, sentiments, and interests of the people should be similar. If this be not the case, there will be a constant clashing of opinions; and the representatives of one part will be continually striving against those of the other. This will retard the operations of government, and prevent such conclusions as will promote the public good.”

Homogeneity is impossible in a territory the size of the United States and is possible only within each state.

The Anti-Federalists unequivocally favored union. Most admitted that the Articles of Confederation needed some revision to make the federal government more efficient at providing defense against foreign enemies, promoting American commerce and maintaining order among the states. But they insisted that this be done without undermining the primacy of the states in the federal arrangement. Unlike the Federalists, they were not persuaded that the challenges facing the country, still in its infancy, could be solved through constitutional reform. What was most in need of reform was the American spirit, which no amount of constitutional tinkering could accomplish. Civic education was vital; as Storing writes, “the small republic was seen as a school of citizenship as much as a scheme of government.”

In any event, the Anti-Federalists maintained that the central question of the proposed national government was not the organization of the government’s powers, as important as that issue was, but the extent of the powers themselves. Power should be granted only cautiously. The broad grants of power in the Constitution, along with the supremacy clause and the necessary and proper clause, would create a government of virtually unlimited powers. Congress, especially in the Senate, lacked sufficient democratic accountability. The complex character of the institutional scheme waters down responsibility, further depriving the government of proper limits. The states themselves would be incapable of erecting any meaningful constitutional barriers to the excesses of federal power. Unlike government under the Articles of Confederation, there would be no participation of the states in the operation of the new federal government. The absence of explicit reservations on behalf of states’ rights exacerbated the danger.

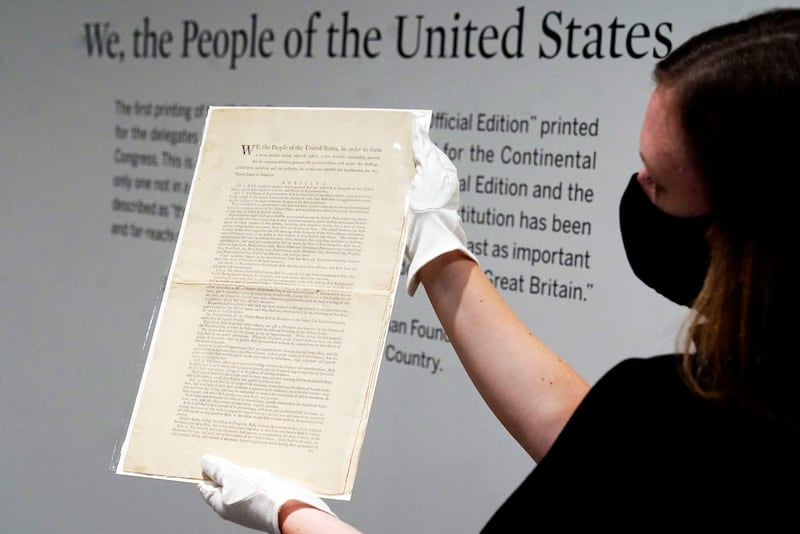

The major constitutional legacy of the Anti-Federalists is the Bill of Rights, the first 10 amendments to the Constitution. The constitutions of many states already included such bills, but the new Constitution was without those explicit protections of liberties. In the Anti-Federalist view, unlimited power (particularly that of taxation) and inadequate representation in the legislature were leading features of the proposed federal government. And, in the words of An Old Whig, “Who shall judge for the legislature what is necessary and proper? ... No one, unless we had a bill of rights to which we might appeal, and under which we might contend against any assumption of undue power and appeal to the judicial branch of the government to protect us by their judgements.”

A bill of rights serves as a reminder of the purposes of republican government and, if rightly understood, will strengthen the people’s attachment to that government. Even so, many Anti-Federalists were pessimistic about the practical usefulness of this kind of “parchment barrier” against a government hell-bent on usurpation. As Storing writes, “The fundamental case for a bill of rights is that it can be a prime agency of that political and moral education of the people on which free republican government depends.”

In the end, Storing concludes, the Anti-Federalists lost the ratification debate because they had the weaker argument. They were guilty, in the words of Hamilton, of “attempt[ing] to reconcile contradictions” instead of “firmly embrac[ing] a rational alternative.” They wanted both union and state sovereignty, the great republic and the small virtuous community, a commercial society and a simple, moderate, sturdy citizenry. Yet the Anti-Federalists’ honest recognition of the problematic character of this novel constitutional experiment is part of their strength and even glory.

The subsequent adoption of a Bill of Rights should establish the justice of including the Anti-Federalists among the Founding Fathers. There is a deeper reason for doing so, however. While the adoption of the Constitution settled many important questions, it did not settle in all respects the shape the American polity would take.

As Storing writes, “If ... the foundation of the American polity was laid by the Federalists, the Anti-Federalist reservations echo through American history; and it is in the dialogue, not merely in the Federalist victory, that the country’s principles are to be discovered.”