On eBay, supporters of former President Donald Trump can buy a 20-by-24-foot banner that perfectly suits his campaign: “Huge & very large,” the description says. Or as some might say, “bigly.”

The previously obscure word, meaning “in a big or impressive way,” burst into the public lexicon after Trump said “big league” during a 2016 debate with Hillary Clinton, and many people misunderstood. For better or for worse, “bigly” has now become associated with Trump, and perhaps not inappropriately so, since so much of the promotion of his presidential bid is, in fact, supersized.

Take, for example, the 6-by-10-foot sign outside Bruce Tattersall’s business in Upton, Massachusetts; for folks driving by on Route 140, there’s no missing the message “Trump 2024. Keep America Great!” even when you’re trying to keep your eyes on the road.

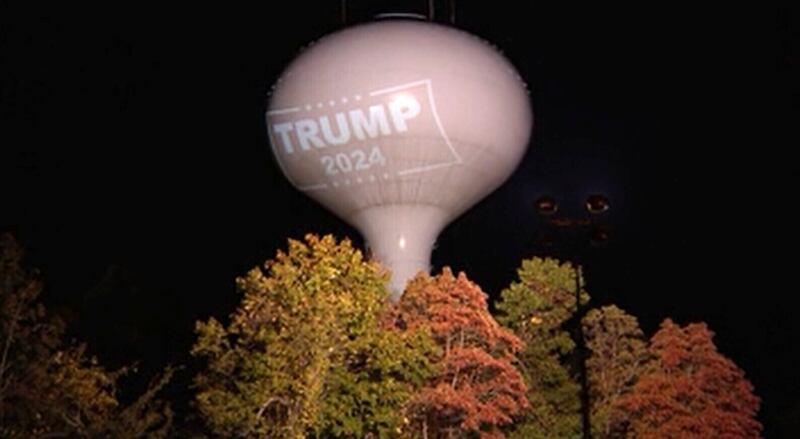

Then there’s the water tower in Hanson, about an hour’s drive away from Tattersall’s sign. The words “Trump 2024″ are being projected on the water tower at night by a local resident, despite a $100-a-day fine and the town’s efforts to block out the words with bright lights. That’s not the only municipal battle over Trump signage; the CEO of Sticker Mule said he was prepared to go to jail over the enormous illuminated Trump sign he had installed atop the company headquarters in Amsterdam, New York. (Turns out jail time wasn’t necessary; at the last minute, a judge ruled that the sign could be lit.)

Elsewhere, a California farmer spelled the name “Trump” in a mile-wide swath of a field. And airplane banners promoting Trump have flown, among other places, over a Taylor Swift concert in Miami.

So why, when it comes to Trump support, is so much of the signage so big?

In some ways, it’s a reflection of what Trump himself says and does, using hyperbole to the extreme and proudly emblazoning the Trump name on his real estate holdings. And of course, people who erect large Trump signs want their candidate to win. A university professor who studies political signs believes there’s more to it than that, and that such signs are as much an outlet of self-expression as they are of politics. But can a jumbo-sized sign make a difference at the ballot box, or are they just sowing discord between neighbors?

‘I’m not trying to be controversial’

While there is no way to accurately tally whether there are more Trump or Vice President Kamala Harris signs in yards across the U.S. as the 2024 Election Day approaches, my own informal survey of neighborhoods in Massachusetts and South Carolina this month yielded plenty of standard yard signs for Harris/Walz, but none that were supersized. That’s not to say that such signs are not available; for example, you can buy a Harris/Walz garage door cover starting at $39.95. (You can also still purchase an 18-by-24-inch sign in the shape of President Joe Biden’s head, now half-price.)

There are also large signs available that mimic the “giant meteor” campaign signs that became popular in 2020, with the punchline “just end it already.”

In putting up a large sign, people risk not only controversy, but vandalism. In 2020, a barn that was painted in support of the Biden/Harris campaign was burned down in Pennsylvania; two teenagers were later arrested and charged with arson. And Newsweek reported this week that several Harris/Walz signs were set on fire in Sterling, Massachusetts, recently.

Bruce Tattersall, the owner of Tattersall Machining, told me he didn’t pay much attention to politics until 2008, when former President Barack Obama was running against Sen. John McCain and America was beginning to experience the Great Recession. By the time Trump arrived on the scene in 2016, he was all in for the candidate, believing that a tough-talking New York businessman could handle America’s challenges. He’s had a Trump sign outside his business for a couple of years, but recently installed one that was even larger — much to the fury of one local driver, who, Tattersall said, drives by each day around lunchtime and lays on his horn. (He knows that the driver isn’t being friendly, because of an obscene gesture he made one day.)

“I’m not trying to be controversial,” Tattersall told me. “I’m just a happy Trump supporter.”

While much of the news is focused on how bitterly divided the country is over Trump — and now, Harris — Tattersall said that for the most part, reactions to the sign have been positive. Some people toot their horns and wave in solidarity as they drive by. And several people have pulled in and asked if they could take a picture. But a few have emailed, asking why he would make such a prominent political statement. And while the sign at the business hasn’t been vandalized, one at his home was destroyed by vandals Wednesday night.

What is the history of political signs?

Political signs have been a thing going back as far as Pompeii. Excavations in the Italian ruins have found inscriptions written in Latin on the ancient walls exhorting people to vote for candidates. One reads: “I beg you to elect Trebius, good man.”

Of course, campaign signs have become much more ubiquitous, and less polite, since the first century before Christ. And the advent of on-demand printing means people can design their own signs instead of relying on whatever a local campaign office brings them.

An article on political signs, published on the website of the Salt Lake City-based company Signs.com, cites studies that have shown a small but still meaningful effect that signs have on the electorate. They work mostly by amplifying name recognition, which is not a problem for either Trump or Harris at this point. (In one study that showed the power of signs, a number of people told a pollster that they were supporting “Ben Griffin,” a fictional person who wasn’t actually in the race — they’d just seen signs with the name placed by the authors of the study.)

But the company notes that rules about signs vary by jurisdiction — California, for example, requires designation of a person responsible for taking campaign signs down within 10 days after the election, and Montana prohibits signs larger than 16-by-4-feet wide.

What signs say about us

Scott Minkhoff, a professor of political science at the State University of New York-New Paltz and co-author of “Politics on Display,” which examines the history and effect of campaign signs, said his research found little evidence that yard signs drive turnout at the polls, and sometimes cause tension in neighborhoods. (One video that went viral on X this week showed a woman knocking on the door of a house that had a small Trump/Vance sign, and then angrily challenging the resident about why she would support him.)

Surveys have shown that only about 1 in 10 households display political signs.

But that’s not to say that signs don’t matter. “I do think there’s a hard-to-measure critical mass thing that can happen if you start to see lots of signs for a candidate that isn’t well known. That creates an informational situation, where people think, maybe I need to learn about this. ... But that’s not what we’re dealing with here when we talk about either Trump or Harris. I doubt people putting out signs is changing the dynamics of the race fundamentally,” Minkoff said.

Minkhoff and his co-authors say that people who install them tend to like signs generally and want others to know where they stand politically. “Some of the other things that predict whether a person will put up a sign include their ideological extremity, their religiosity, their personality (extraversion), and their propensity to initiate political conversations,” they write.

He hasn’t seen oversized signs for the Harris/Walz campaign, but has seen several large Trump signs in his “purple” district. “Going back to 2016, Trump supporters have been pretty open about being Trump supporters. They like the hats and the buttons and the signage, and this reflects that.” There also may be a contagion effect with large or unusual signs — when people see one, they may desire their own, and media coverage may amplify that. But the size of campaign signs and their effectiveness isn’t something that has been well studied.

“But, I do think that Trump voters are behaving differently with respect to signs. It does look like that,” he said.