Family, friends and political leaders gathered at Washington National Cathedral to remember the life of former Vice President Dick Cheney on Thursday morning.

Here are some of the most memorable moments shared during the funeral.

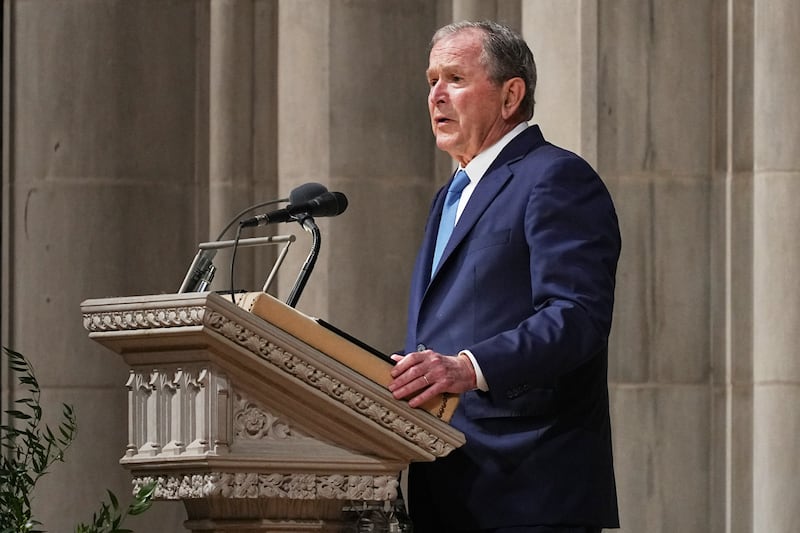

Former President Bush: From search committee to running mate — and kindergarten show-and-tell

Former President George W. Bush used his eulogy to talk less about the global crises they navigated together and more about the quiet, steady man at his side.

He recounted asking Cheney — a former White House chief of staff and Defense secretary — to lead the search for a running mate in 2000. After reviewing name after name, Bush said he eventually realized “the best choice for the vice president was the man sitting right in front of me.”

At that point, Bush said, “most in his position would have jumped at the chance.” Cheney, instead, calmly laid out all the reasons not to pick him and even invited a skeptical adviser to make the case against him. Bush chose him anyway, later telling mourners that “they do not come any better than Dick Cheney.”

The former president also shared one of his favorite family stories: Cheney appearing at his grandson Richard’s kindergarten show-and-tell.

The vice president’s visit was a hit. “As a matter of fact, the teacher told Dick that that was the most exciting show and tell since the morning a little girl brought her cow to class,” Bush said, drawing laughter in the cathedral.

Bush said that moment captured how Cheney balanced immense responsibility with deep devotion to his grandchildren — the same man who once presided over war councils later sitting on a tiny classroom chair answering questions from 5-year-olds.

Liz Cheney: Doughnuts, battlefields and the Carpenters

Daughter Liz Cheney framed her father’s life around a different kind of road trip.

When she and her sister Mary were young, she said, their dad would load them into the family station wagon — Krispy Kreme doughnuts in the back — and drive to Civil War battlefields like Gettysburg, Antietam and Manassas. With no seat belt laws and long drives ahead, the girls would sprawl out and groan as their father stopped at every historical marker.

“As you might imagine, Dick Cheney read every word of every sign at every battlefield, museum and national park he ever visited,” she said. As children, they complained. But they also learned that “no one was going anywhere until he got done,” so they started reading the signs too. “And what an education we got.”

She also filled in early chapters of his life story. If Dick Cheney heard anyone say that he flunked out of Yale, he would correct them. “No, no. I was asked to leave — twice.”

In the fall of 1963, he transferred to the University of Wyoming and climbed to a seat up near the rafters of the fieldhouse to hear President John F. Kennedy speak about public service. Liz said she believes that was the moment he decided what direction his life should take.

And while he eventually became a Republican, she said her father believed “bonds of party must always yield to the single bond we share as Americans. For him, a choice between defense of the Constitution and defense of your political party was no choice at all.”

Later in life, she was the one driving him — on new road trips to old sites like Antietam and Mount Vernon, with her dad in his Stetson hat, a copy of The Economist, the day’s newspapers and a book tucked in the door pocket. She said that he would often choose the soundtrack of their road trips — Johnny Cash, John Denver and even the Carpenters.

To be in his presence, she said, “was to know safety and love and laughter and kindness.”

The night before he died, Liz Cheney said, clouds above her parents’ home formed shapes like winged angels. Cheney’s last words were to tell his wife, Lynne, that he loved her.

Cheney’s grandchildren: ‘Vice president turned rodeo grandpa’

One granddaughter, Grace Perry, described being on the high school rodeo team in Jackson, Wyoming, with Cheney as her driver. In his Ford F-350, he hauled her and her horses hundreds of miles across the state and “never went anywhere unprepared,” stocking the truck with emergency blankets, tool kits, knives, fly rods, rain gear and snacks.

“I’m pretty sure he’s the only person who ever had the title vice president turned rodeo grandpa,” she said. “And I’m blessed he was mine.”

Once, a reporter from The Wall Street Journal wanted to interview him at their horse trailer. Just before the journalist arrived, they realized the cramped living quarters were a mess.

“Grandpa, we cannot have a Wall Street Journal reporter in here. They’re going to take pictures,” she told him.

Cheney agreed. “Let’s shove everything in the bathroom,” he said. After they crammed the clutter behind the door, he gave one last instruction: “Gracie, whatever you do, do not let the reporter use the bathroom.”

Another grandson, Richard Perry, who was named after the vice president, remembered how Cheney came to nearly all his high school football games and kept the schedule on his desk.

Both Cheney and his grandson were running backs, though one of Cheney’s coaches once joked that he “ran with the speed of a fence post.”

Cheney’s real lesson, his grandson said, was that “raw determination and grit can lead you to success,” even if you’re not the fastest on the field.

He concluded by describing the way Cheney looked at them when he smiled — how, without saying a word, “his gaze alone said, ‘I love you more than anything.’”

Cheney’s cardiologist: ‘The easiest patient to care for’

Dr. Jonathan Reiner, the cardiologist who treated Cheney for over 27 years, described a relationship built on trust and stubborn determination. Two decades before they met, Cheney had a heart attack at age 37 while running for Congress. His doctors quietly believed he should pull out of the race.

“They didn’t know Dick Cheney,” Reiner said. After a period of rest, Cheney went back to Wyoming voters, told them “he was up for the challenge,” that “a little hard work never hurt anybody,” and went on to win that race and five more.

Reiner said that despite “very complex heart disease,” Cheney was “the easiest patient to care for” — meticulous with his medications and fond of the motto, “When in doubt, check it out.” Politics, Reiner said, “never” affected Cheney’s medical decisions.

There was only one time Cheney refused a recommendation: Sept. 11, 2001.

That afternoon, as Cheney moved to an undisclosed location, delayed lab work came back showing his potassium level was dangerously high. Reiner believed the reading was probably wrong — but too serious to ignore — and asked if they could repeat the test immediately.

The answer from the vice president, in the middle of the worst terrorist attack in modern U.S. history, was firm: “No, not today.”

“I didn’t think that was the day to argue with him,” Reiner said.

Years later, when Cheney lay near death in a cardiac intensive care unit, doctors told him they couldn’t wait until morning to implant a mechanical assist device.

“He looked for a moment towards Mrs. Cheney, Liz and Mary, and then said calmly, ‘OK, let’s do it,’” Reiner recalled. That surgery and later a heart transplant gave Cheney more years of fly-fishing on the Snake River and “most profoundly, precious time to watch his seven grandchildren grow up.”

Reiner asked mourners to also remember the “anonymous family” who, in their own grief, gave Cheney a donor heart — “a blessing and an act of love” that extended his life and his time with family.

Pete Williams: Government work and the man behind the public image

Former NBC correspondent Pete Williams, who served as Cheney’s press secretary at the Pentagon, said that in private, the powerful official who carried nuclear launch codes was surprisingly unassuming.

His calls, even from the White House, would begin the same way: “Hi, John, it’s Dick Cheney,” he told Reiner. To one young cardiology fellow who didn’t recognize him and asked what he did for a living, the soon-to-be vice president simply answered, “Government work.”

Williams said his old boss respected public servants so much that, when the word “bureaucrat” appeared in a news release he’d drafted, Cheney crossed it out and replaced it with “federal official.”

Williams remembered a letter from an Indiana woman during the Gulf War who wrote that it was reassuring to see someone “plain speaking, resolute and strong” in charge of the military. She added, “I find these qualities to be very attractive. I’m not sure whether you’re married, but if you’re ever in Indianapolis, you can look me up.” Cheney took the letter home “to brag about it,” Williams said.

And when a White House initiative on nuclear arms control leaked to The New York Times before President George H. W. Bush announced it, Cheney’s staff braced for a dressing-down.

“We walked in and sat down, braced for the worst,” Williams recalled. Cheney told them, “I’ve got some good news and some bad news. … The bad news is that the president of the United States is very angry with you both.”

Then came the good news: “I only have to fire one of you.”

Williams realized he was joking. Cheney then told them, “It’s OK, guys. I told the president it was my idea.” He took the blame, Williams said, and “saved us from ourselves,” a move that inspired loyalty among staff who knew he would not abandon them when they made mistakes.

Who was in attendance

The service drew a bipartisan crowd.

Former President George W. Bush sat with former first lady Laura Bush next to former President Joe Biden and former first lady Jill Biden. Former Vice Presidents Kamala Harris, Mike Pence, Dan Quayle and Al Gore also attended, a rare gathering of people who have held the same office Cheney once did.

According to The Associated Press, Republican Sen. Mitch McConnell, the former longtime Senate leader, and his wife, former Labor and Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao, were in attendance. Behind them sat Democratic Rep. Nancy Pelosi, the former House speaker, who spent time talking with another former speaker, Republican John Boehner.

President Donald J. Trump and Vice President JD Vance were not invited to attend the funeral.