Editor’s note: Third in a series remembering Kresimir Cosic.

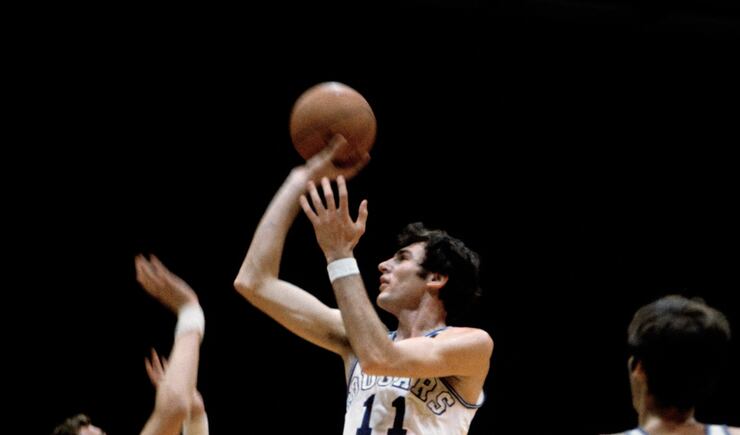

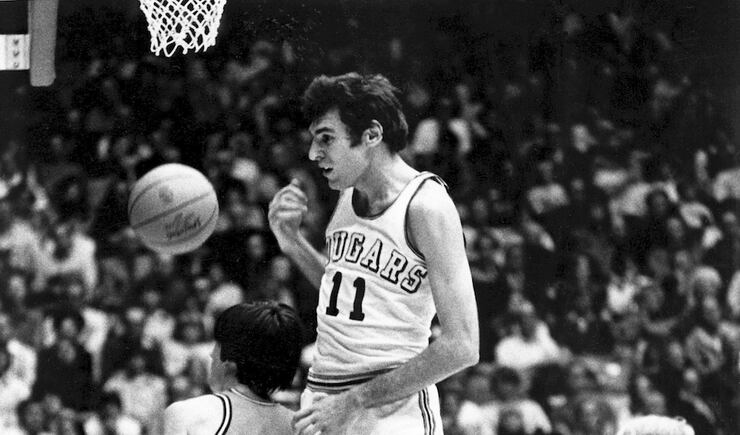

PROVO — He was a guard playing in a center’s body. Doug Richards says his late teammate Kresimir Cosic was coachable, but unpredictable as a lightning storm as he galloped into BYU lore.

In Cosic, BYU had a center who played like a guard. Cosic pioneered the prototype Euro basketball player who worked angles, played the whole court, mastered different shots and worked fundamentals into the ground.

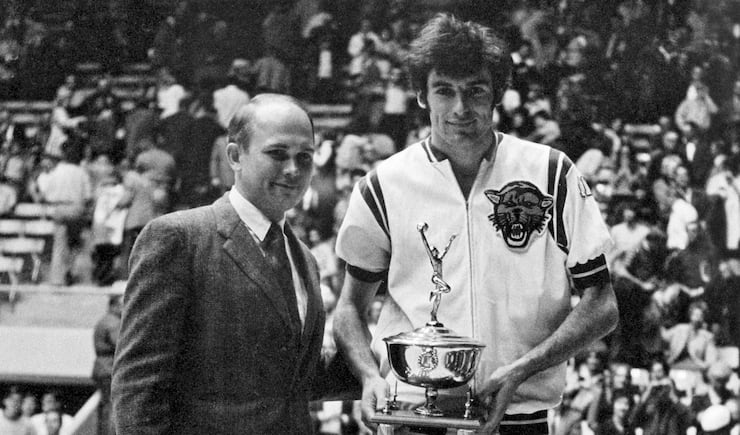

He was the first European to be named an All-American, the first European to be drafted in the NBA. He led the way as an idol for NBA stars Drazen Petrovic and Toni Kukoc.

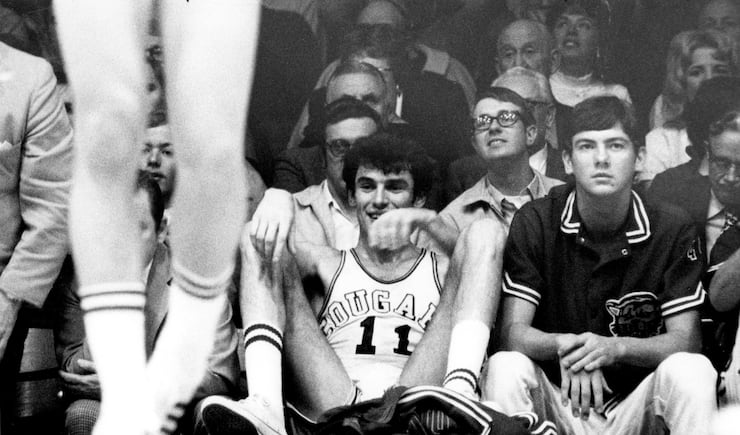

But back at BYU, fans saw the heart of the player. He thought he could do everything. Sometimes he did.

Back in the day, Stan Watts fired up the fast break. Quick outlet passes, guards blistering down the court for a three-on-one or two-on-one with a trailer. Cosic liked to start and finish the break. It ticked off guard Bernie Fryer, who’d curse at times when Cosic grabbed a rebound and led the break.

Fryer later had a long and storied career as an NBA official.

After Watts’ retired and Glenn Potter took over in the middle of Cosic’s BYU career, the pace was slower, but that only led Cosic to believe he needed to help the guard line by leading the fast break parade.

“It bugged Bernie and Belmont Anderson and they often told him, but I didn’t mind it so much,” said Richards. “But it may have cost us an NCAA Tournament game against UCLA in 1972 when we lost to Long Beach State. Cosic probably led the break too much in that loss.”

But Cosic thought he could get it done.

“If we’d have won that game, we’d have played the Bruins in the Marriott Center and made the Sweet 16. It was back when there were only 32 teams and UCLA had won a string of championships. I would have guarded Henry Bibby and Cosic would have had Bill Walton on him and I’m sure he’d have taken Walton outside and made him guard him away from the basket,” said Richards.

BYU ran a high post rub with Cosic. It was a play where the guards would run past Cosic at the top of the key as close as they could, then a forward would make a rub, then a guard. The first time BYU ran the play in a game, Richards rubbed off Cosic and cut to the basket. The big Croat flipped him a pass without looking, just flipped it over his head to Richards, who laid it in. The crowd went nuts.

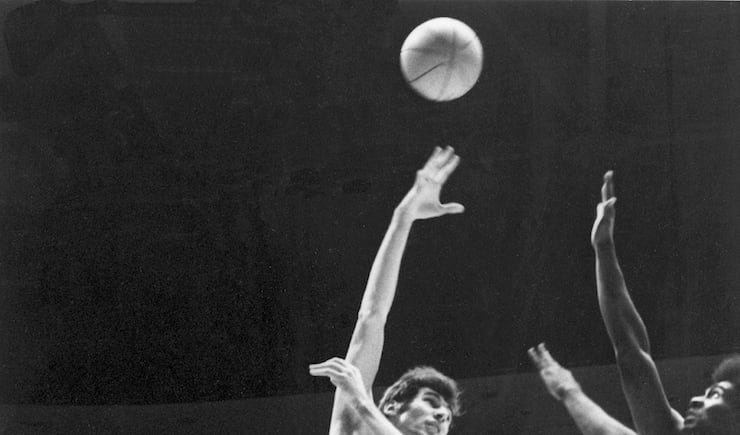

Cosic would sometimes spin out of that play, drive to the hoop and stretching out his frame after bringing his knees to his chest, make an underhand layin at full speed. At 6-foot-11 and about 200 pounds, he caused a problem for other centers. He could dribble around them inside the key and stretch out for underhand layins or outside hooks with either hand, or take his defender outside and plop in a 20-foot jump shot. He was a deadly passer.

Potter remembers the last season playing in the Smith Fieldhouse, Cosic was at midcourt with his face to the basket when Fryer hit him with a pass. Cosic took the ball, flipped it between his legs to a cutting Phil Tollestrup for an easy lay-in. “He was so fun to be around.”

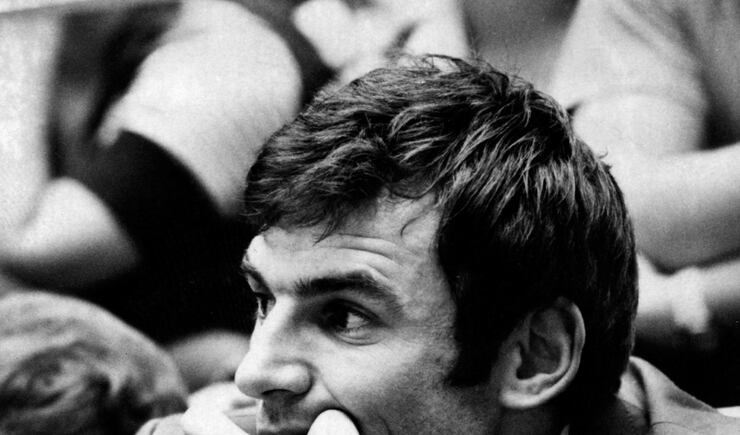

“I just loved the guy. He was gregarious, funny. He’d sing in Croatian with his deep, deep voice. He was a tremendous teammate,” said Richards.

“I wouldn’t say he was not coachable,” Richards explained in an interview with historians. “But at times he would do his own thing because he would want to, like, get the rebound and then lead the fast break. And at BYU we were taught that the big guys got the rebound, and they fired it out to the guards, and the other guard came in and got it, and then we’d go down to get a fast break.

“He’d do that himself sometimes. He was so unorthodox that he would still take some outside shots, where most coaches would throw their hands up. Or, he’d make some no-look passes, which were so unconventional. From that standpoint, he was unique and he was a challenge to coach Stan Watts, who was a saint. Coach Watts had patience, so did coach Potter.

Dan Paxton, a former BYU student, remembers the legend.

“One great memory I had from Cosic was on Dec. 22, 1971,” said Paxton. “I was in the Army and came home for Christmas and went to the BYU vs. USU game in the Spectrum in Logan. You know how loud the Aggies fans can be so this is an amazing event. Cosic took a long rebound and drove the ball the length of the court, took the ball around his back, faked a pass to the right and then threw a behind-the-back bounce pass to a streaking player on the left for a layup. The USU fans went silent, they had just witnessed greatness, unlike anything they had seen in Logan. He was the most amazing point guard at 6-11.”

Richards said Cosic was a unique player. He didn’t miss a practice and he wasn’t lazy. He showed up and learned. It was a new style for him and he had to try and fit into a team concept.

“He’d been ‘The Man’ over there (Yugoslavia). He’d already played in the ’68 Olympics for Yugoslavia the year before he came to BYU.”

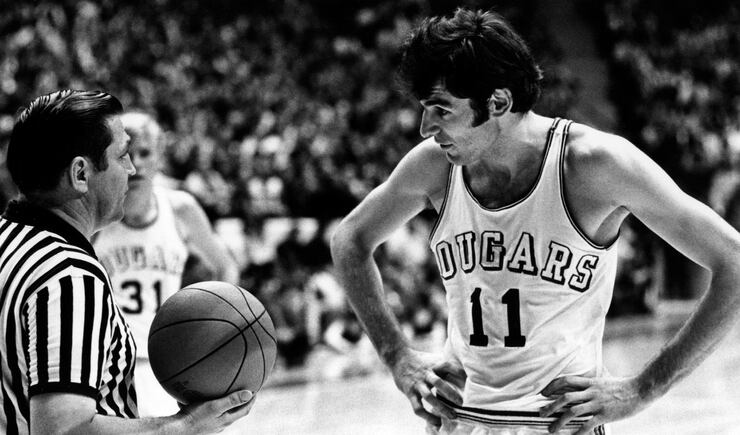

In one home series against Arizona and Arizona State, Cosic got mad at the way the game was being called and swore in Croatian. One of the officials, the late Rudy Marich who had ties to Eastern Europe, understood exactly what Cosic had said and gave him a technical foul.

The crowd was getting heated, they had no idea what Cosic had done to earn a technical.

When Marich made another call fans thought was bad, an otherwise mild-mannered fan took off his overcoat and tossed it to the court where it wrapped around the official.

Richards remembers the public address announcer, head track coach Clarence Robison, got on the microphone and rebuked in his deep voice, said, “Remember who you are.”

Richards wondered what in the heck was going on. Nobody on the team knew what Cosic had done to earn a technical. He asked Cosic about it, who was smiling. “I said some bad words in Croatian.”

That became part of the Cosic lore.

In another game, Richards said a player in the WAC delivered a cheap shot at Cosic. “He really didn’t know how to fight. He ended up backhanding the guy and broke a bone in his hand,” said Richards.

In a game at UTEP against the legendary Don “Bear” Haskins, UTEP had never lost a league game at home. Down one point with 20 seconds left the Cougars had a chance for a win with 20 seconds left and called time out.

“Coach Potter called timeout and he took out a chalkboard and began writing up a play with lines and arrows all over. When he got done, you couldn’t tell what it was. As we broke the huddle and headed for the floor, Cosic leaned down and whispered to me, ‘Just pass me the ball.’” — Doug Richards

“Coach Potter called timeout and he took out a chalkboard and began writing up a play with lines and arrows all over. When he got done, you couldn’t tell what it was. As we broke the huddle and headed for the floor, Cosic leaned down and whispered to me, ‘Just pass me the ball.’”

He did, and Cosic made the game-winner, a dribble-drive jumper from the top of the key.

Potter said the play, he remembered, called for Cosic to get the ball and decide to pass or shoot. “He dribbled to the top of the key, set himself and hit what would have been a 3-pointer today for the win.”

Richards fondly remembers Cosic telling him in games, “You go, I get you the ball. I get you ball.” His passion was infectious. He was funny. He was complex. He was talented and unpredictable.

“He wasn’t the easiest to coach. He was kind of like a wild mustang,” said Richards.

By the time Cosic’s BYU career was over, the new Marriott Center was packed to the rafters. The university had built a basketball palace and Cosic had helped fill it.

A Sports Illustrated article at the time read: “His zest for the game ... was something to behold. He was forever clapping his hands, raising fists high, laughing, shouting ‘Opa! Opa! (I’m open, I’m open.’) He jackknifed for layups, dribbled through his legs, passed behind his back and joyfully fired all manner of shots from improbable positions and angles.”

Cosic set the BYU record for points scored in a career (1,513), topping a mark Joe Nelson set in 1950. He is now 17th after the 3-point era helped erase his mark. He set BYU’s record for field goals made (566), now 13th. He became BYU’s all-time leading rebounder with 919, now he is No. 3. He remains the No. 2 rebounder per game with an 11.6 per game average after 47 years of aspirants climbing the statistical ladder.

He set the school mark for 20-point games with 38 and is ranked No. 6 right now.

Cosic remains BYU’s record-holder for career consecutive double-doubles with 10 and career double-doubles with 48. He holds the record for most games with 15 or more rebounds with 21. He set the record for field goal accuracy that still stands today when he made 12 of 12 from the field against Arizona on Feb. 26, 1971.

In short, Cosic became BYU basketball’s superstar in the game’s largest college arena preset by the success of Watts. In the transition from the Smith Fieldhouse, Cosic helped set the stage for the Danny Ainge era which followed a few years later when Frank Arnold left UCLA for BYU and replaced Potter. It was an era when the new arena was sold out all the time.

Cosic was drafted by the Portland Trail Blazers in 1972 with the first pick in the 10th round, but returned to BYU as a senior. That summer, the Los Angeles Lakers drafted him in the fifth round, and Carolina of the ABA also drafted him. Knowing he might return to Zadar to play European ball, the Lakers did not sign Cosic. And left America to play for his hometown of Zadar for $200 a month.

Richards said Cosic could have been drafted higher but the NBA worried about his slender frame in a game where Kareem Abdul Jabbar and Bill Russell were the prototype center post players. “There is no doubt in my mind if he’d played in the NBA, he’d have become a star and made a fortune.”

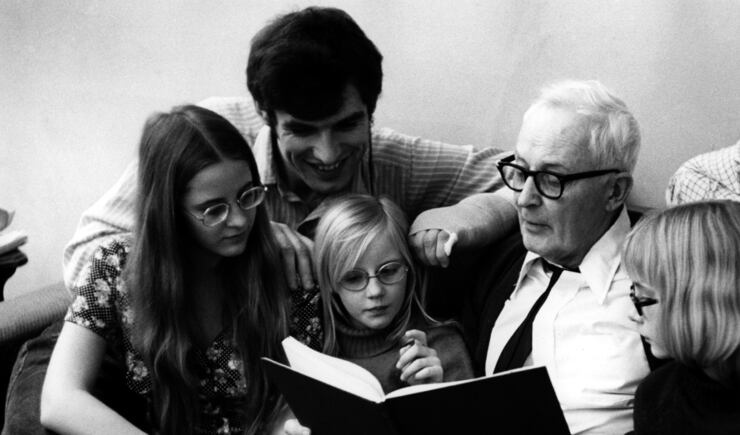

But the huge draw of returning home where he was already a legend tugged at Cosic. He was homesick and longed for his friends and teammates on his Zadar team and Yugoslavia’s national squad. He also had felt a deep conviction that he had a special message to share with his countrymen after converting to the Latter-day Saint faith.

Richards was drafted by Portland in the seventh round of 1974 NBA draft. Because of his brother’s connection to the Dallas Cowboys as a star receiver, personnel director Gil Brandt approached Richards about getting drafted and playing in the NFL.

But on the other side of the world, Cosic kept writing and calling Richards to come to Yugoslavia and play with him on Zadar’s team. Richards didn’t quite know what to make of it. He was about to be engaged to a dancer on BYU’s Young Ambassadors, Kerry Harris, and felt the urgency to put a ring on her finger.

In one of his conversations with Cosic he asked Cosic what his address was in Zadar because he’d lost it.

“Look,” said Cosic. “Just put ‘kosarkaski’ on it. In care of kosarkaski with a ‘k’ which is basketball in Croatian. Care of Kosarkaski Klub, Zadar, Yugoslavia, Europe.”

And then he told Richards, “If you forget how to spell it, put ‘Kresimir Cosic, care of Europe. It get to me.”

Next: Cosic as star, statesman and missionary