Editor’s note: Last in a five-part series on Kresimir Cosic

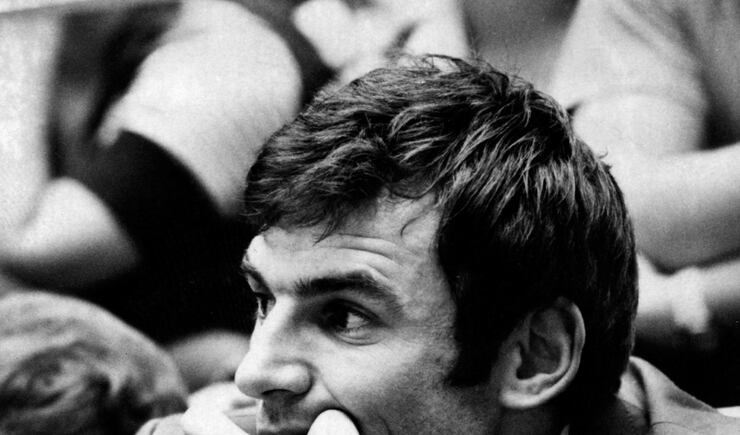

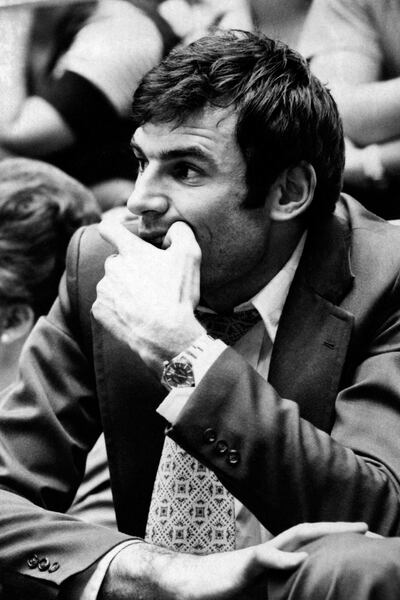

PROVO — Superstar athletes endorse and sell everything from shoes to cars, shaving blades to watches. A mega-world star in the 1970s and ’80s, Kresimir Cosic could have made a fortune, but instead, he chose to preach his faith in Croatia and bounce a ball at the same time.

And it wasn’t easy.

The Communist Party in the former Yugoslavia cut Cosic a lot of slack for proselyting his beliefs in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but often warned and threatened him. Communists were wary of an emerging movement led by one of their leading sports figures.

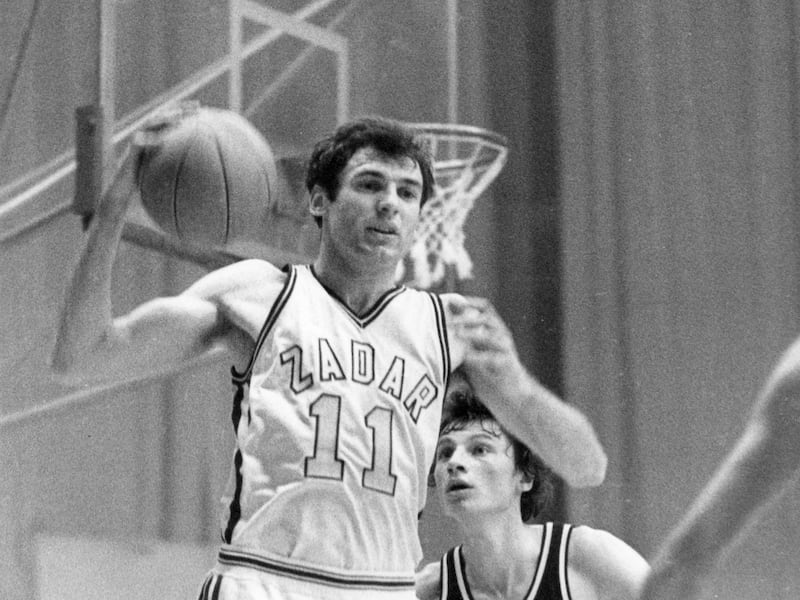

After leaving BYU and turning down the NBA, Cosic pressured former BYU teammate Doug Richards to leave the St. Louis Spirits of the American Basketball Association and an opportunity with the NFL to play on his team in Zadar. Richards thought he was crazy and resisted until Cosic revealed his real motivation.

“I need someone else with the priesthood here,” Cosic said.

Richards did go to Zadar. He did play in smoke-filled arenas where you could barely see the opposite basket from the other end of the court. Additionally, before leaving in 1974, he was set apart as a special missionary by Elder Bernard P. Brockbank, an ecclesiastical supervisor of the area for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Richards did help Cosic minister to Croatians.

At the time, of course, he did not know Cosic would pass away 20 years later at the age of 46 in Maryland as Croatian Deputy Ambassador to the United States.

Richards also did not know he would return to Croatia many times — as late as a few years ago — to help missionary efforts, celebrate Cosic’s life, speak of his former teammate, organize tournaments in a country that still loves Cosic and pass by monuments, streets and an arena named after his teammate. Richards has attended branches of his church Cosic helped lay the foundation for.

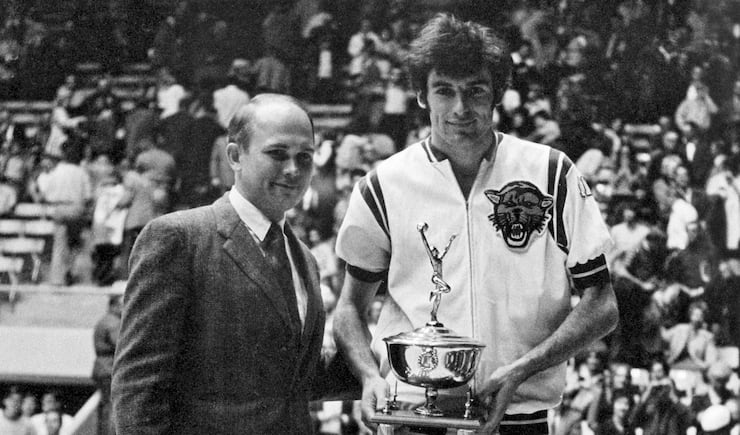

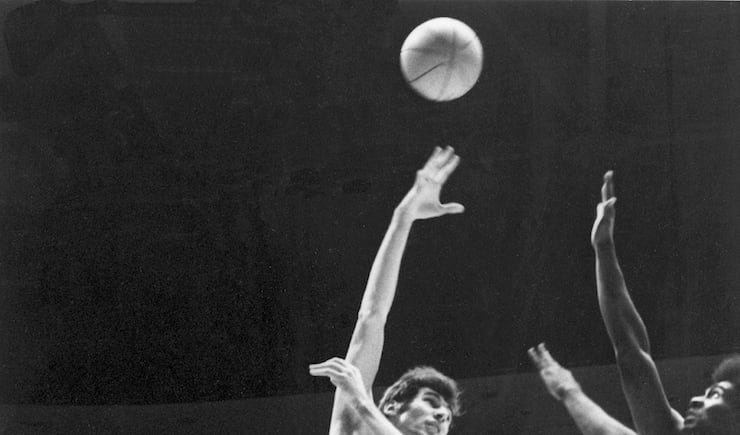

Cosic’s athletic stardom continued post-BYU for years. He led Yugoslavia’s national team to Eurobasket titles in 1975 and 1977, a FIBA World Championship title in 1978, a silver medal in the World Championships in 1974, Olympic silver at Montreal in 1976 and gold in Moscow in 1980.

Once while coaching Yugoslavia’s national team, Cosic was in Italy and secretly slipped in to see a game in Bologna. When arena officials learned Cosic was in the house, an announcement was made and he received a standing ovation for about 10 minutes, according to Vlado Vanjak.

His fame in Europe as the first European drafted to the NBA opened the door for the likes of Drazen Petrovic, Arvydas Sabonis, Vlade Divac and Toni Kukoc.

Like he did with Richards, Cosic drafted his former coach Glenn Potter to come to Croatia “to help coach the guards,” but to also help him deliver his faith to his native country. One day, while walking in Zadar with Cosic, a friend came running up and in an exasperated voice, began talking to Cosic excitedly in Croatian. When the friend left, Potter asked Cosic what was said.

“He said he just came from a Communist Party board meeting and a member of the board told him to warn me that if I didn’t stop proselyting and preaching, they would put me in a mental institution.”

“That sounds serious,” said Potter.

Laughing, Cosic replied, “They would not dare. I am the most popular athlete and all of Yugoslavia and people would not stand for me to be put in a mental institution.”

One of Cosic’s first converts was lifetime friend Miso Ostarcevic, who followed him to BYU and later helped with missionary work. Cosic and Ostarcevic baptized Ostarcevic’s wife Ankica in the Adriatic Sea on a secluded beach they found for privacy at 2 a.m.

Miso and Ankica now live in St. George, Utah.

When Potter left Yugoslavia on one of his visits, he saw a magazine at the airport with Cosic on the cover. Half the photo of Cosic was in color, the other in black and white. Potter brought it back to BYU for someone to translate it to English.

The title was: “The Good and Bad Ways of Kresimir Cosic.”

The interviewer pressed Cosic on his religion, his faith. Cosic answered with concise answers about the law of chastity, a lay ministry, where he believed humankind came from, why they were here and where they were going. He cited the Articles of Faith of his religion.

The writer of the article asked Cosic, “Couldn’t you have directed that energy toward more valuable things like science or social organizations whose programs are far more concrete, human and progressive?”

Cosic answered, “Before I came to the United States, I lived a life being too young to be seriously involved in anything. Communism is OK, but now I believe.”

“Before I came to the United States, I lived a life being too young to be seriously involved in anything. Communism is OK, but now I believe.” — Kresimir Cosic

The interviewer concluded: “We have come to this conclusion in some of our athletic organizations, we have failed to introduce the educational system and especially the one concerning the ideological and political education; the fact is, unfortunately, with athletic capabilities we did not have time to teach these young people about more important social factors in the race for better scores and good athletes, we forgot about the human and educational matters of our young people.

“Cosic, without that background, went to the United States, as one of his teammates said, left on his own, in a distant world, and took on fanaticism.” The author said society, along with sports, could surely help Cosic turn away from this way of thinking, back to real human values.

Potter began thinking to himself, “Kresimir is alone. Cosic is the only Mormon among 12 million people and to see that kind of pressure that was put on him or would be put on him is just unbelievable.”

In time, Cosic worked with nearby missions to get full-time missionaries to serve in his country — only to answer questions, not teach. Some were kicked out of the country, others returned through the efforts of Cosic. He was later instrumental in filing legal papers for his church to be recognized officially, obtaining property for places of worship and introducing many high-ranking church officials including LDS apostles on Croatian soil. These included the late President Thomas S. Monson and current church President Russell M. Nelson.

President Nelson’s visit in 1987 came when Cosic arranged a meeting with Croatia’s Vice President Pero Pletikosa, Dr. Vitomir Unkovic, the minister of religion, and Radovan Smardzic, the minister of religious affairs for Yugoslavia.

After the meeting, Smardzic asked Cosic for his autograph for his son, who idolized him.

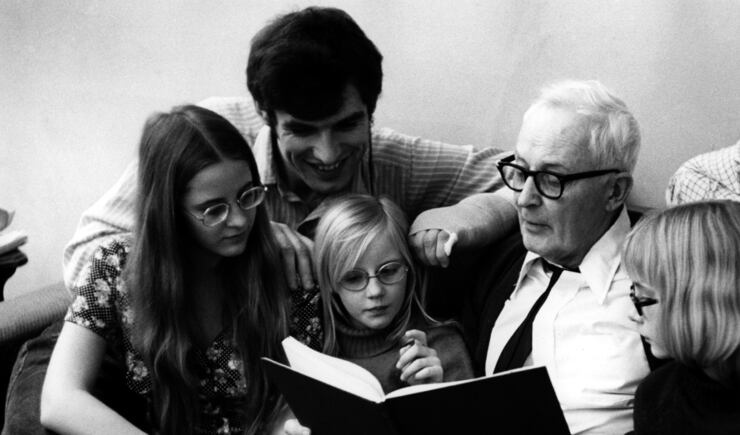

Cosic married a French professor, the love of his life, Ljerka Kobasic. They had three children, Ana, Iva and son Kresimir Petar. Ana later attended BYU where she played basketball. His son was born when he went to Washington, D.C., as a diplomat before his death 25 years ago this May.

BYU has established a scholarship fund for any of his children to attend school in Provo if they desire.

Cosic stopped playing basketball in 1985, but did coach the national Yugoslavian team, and the following year his squad won the bronze medal in the World Basketball Championships. That feat extended Yugoslavia’s 23-year streak of finishing in the top three of those championships.

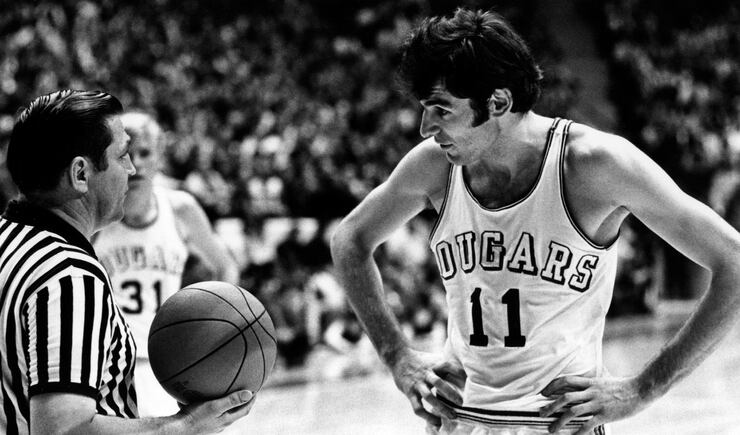

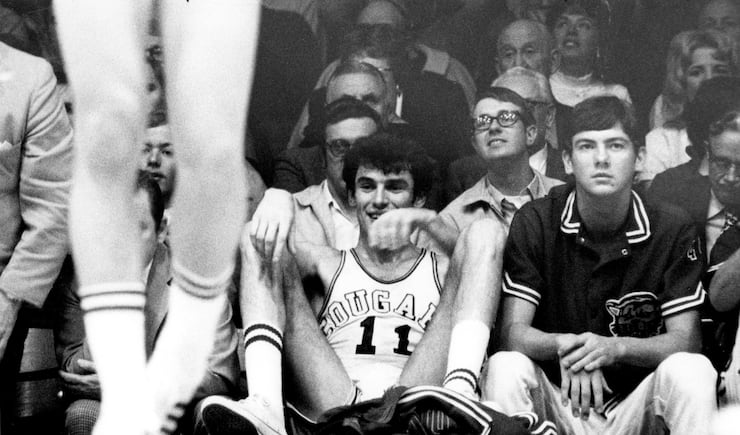

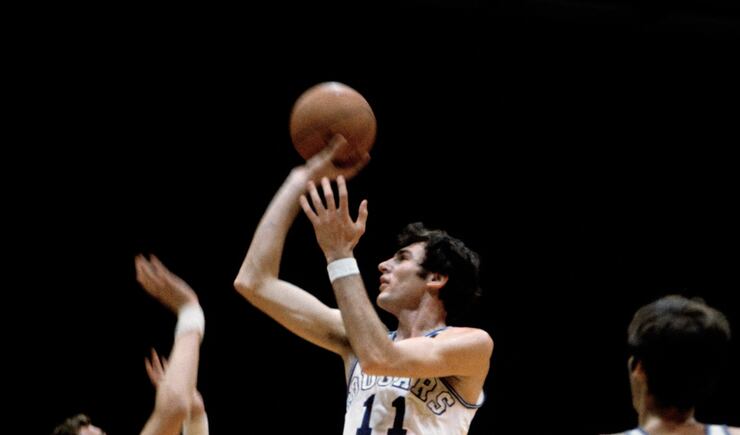

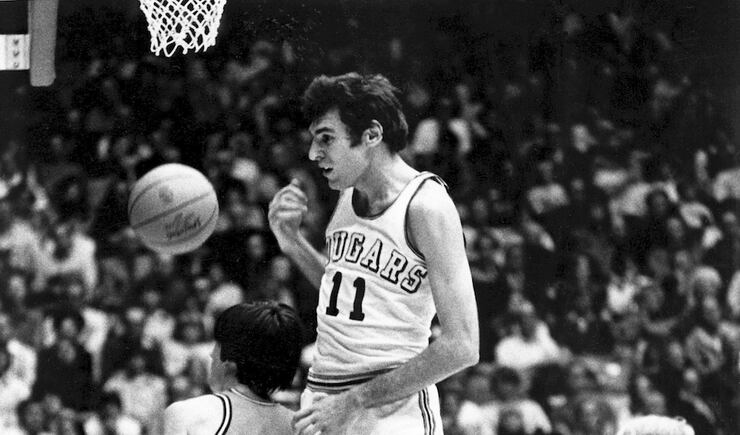

Cosic passed away May 25, 1995, after battling cancer, his life cut too short. In his lifetime, he accomplished remarkable athletic, spiritual and diplomatic achievements. For a generation of BYU fans who sit in the ROC section of the Marriott Center and look up at the retired jersey No. 11, it will be a glimpse of a symbol that stands for a player none of them ever saw play, who died before almost all were even born.

Cosic was an elite basketball talent and mind, and a fiercely gifted human who, in the end, spent his life protecting and standing up for God and the love of his country.

There was only one Kresimir Cosic.

There will never be another.