The news that 215 unmarked graves were found near the site of the Kamloops Indian Residential School in western Canada did not surprise Manny Jules. A former chief of the Kamloops band, Jules attended the school in the 1950s. He told me, “It’s part of our oral history that there were children buried and burned in furnaces.”

The graves are only a tiny echo of the 4,000 or so indigenous children who died either from neglect or abuse in now-defunct residential schools.

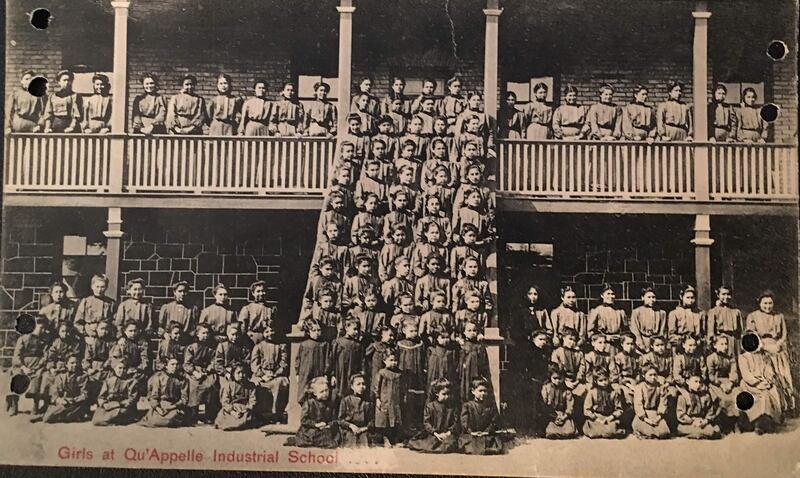

The schools, which operated both in Canada and the U.S., were run mostly by Christians from the Catholic or Protestant traditions, and operated from the 19th century well into the 1970s. The aim of the institutions was largely to assimilate the Indian population, yet thousands died.

Jules said that although he was one of the first Indian children who was permitted to live at home and attend the school, he still bore the brunt of some of this abuse. He remembered that the priests used to hit them in the head “so no one would see the marks.”

Thanks to recent technology that allows the detection of these graves, we will likely be hearing about many more of them, both here and in Canada. While much of the Indigenous population and their supporters are focused on the apologies that are due to these bands and tribes (Jules would certainly appreciate one, too), many are more interested in ensuring that Kamloops and the other bands finally get the autonomy they need to become financially independent from the government and to ensure that the similar atrocities will never happen again.

Chief Louis, one of the band’s former leaders, actually requested that a school be opened on the reserve, according to Jules. Because the chief lived through the smallpox epidemic of the 1860s, “he knew we needed professionally trained and educated people,” especially doctors.

“He wanted our people, his people to compete on better terms with whites,” Jules said, who also felt this calling, giving up his dream to be an artist in order to take on the burdens of leadership. Though the school itself has been closed, the band has kept the building open as a community center “to honor Chief Louis’ legacy.”

But as Jules notes, the bands need something besides education. They need property rights, and the they need a tribal government that can tax residents and spend the money on local priorities like any other city or town government. But under Canada’s laws, just like those in the U.S., Indigenous lands are held in trust by the national government, which means that Native people cannot buy or sell the land without the approval of a bureaucrat. Even if they get the approval, they still don’t have a title to it. They wouldn’t be able to get a mortgage on their property or borrow against it to start a business.

The city of Kamloops (population 90,000) enjoys a gorgeous setting. In the heart of the area is the confluence of the North and South Thompson Rivers — the former flowing from the Thompson Glacier, the latter coming from Little Shuswap Lake. In the summer, Canadian and international travelers eager to experience the region’s natural beauty come in busloads. Railway lines meet here, so the region is a hub of economic activity. There are coal mines and copper mines. Natural resources are plentiful.

But if you want to see how the land question affects members of First Nations, drive at night to the top of one of the peaks overlooking the city. On one side of the river, there are lights everywhere — apartment buildings, homes, businesses and hotels. On the other side — the land held by Jules’ band — there’s mostly darkness. It’s not quite as stark as the difference in satellite images between North and South Korea, but it comes remarkably close.

“The majority of the kids I went to school with are dead.” — Manny Jules, former chief of the Kamloops band

The first thing you notice when you drive to the other side of the river is the waterfront. Right on the edge of the rivers is a trailer park with hundreds of homes on top of one another. A little way back from that are some lumberyards and car dealerships interspersed with small homes, many of which are badly in need of repair.

Much of this part of town has a feel of impermanence to it. That’s no accident, explains André Le Dressay of Fiscal Realities, a group that conducts economic research. In the Kamloops area, Le Dressay estimates that a First Nation member–owned home is worth about 1/20th what it’s worth if it were off the reserve. Development on the Indian side of the river takes, on average, four to six times longer than development on land off of the reserve. The lack of property rights has left Jules’ band and many others in a state of permanent dependence on Canadian authorities. Even projects that the band wants to undertake are stifled by a tax system that allows the provincial government to collect seven times more revenue than then tribal government can collect.

“The majority of the kids I went to school with are dead,” Jules said, “because of the experience they had, the abuse, the separation (from their families and communities).” But Jules knows that official apologies are not the key to moving forward, nor are more government programs designed to help. “Programs just beget more programs,” he said.

When Jules looks around at the different pathologies affecting First Nations — from low levels of education to drug abuse to poverty to domestic violence — he said, “We have ingrained in us the mentality that it’s someone else’s responsibility. We have seen a complete abdication.” For things to get better, “the leadership has to come from us.”

Naomi Schaefer Riley is a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a Deseret News contributor. The paperback version of her book “The New Trail of Tears: How Washington Is Destroying American Indians” will be out this fall.