Texas legislators offered “refuge” by Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker? And Texas Gov. Greg Abbott issuing civil arrest warrants for these same state Democrats?

All this sounds very strange to many Americans, even if they understand the potential impact of five new Republican seats in the U.S. House that could be generated from an effort to redraw the Texas electoral map.

A little more historical context might help, reminding us how far back in American history accusations of biased redistricting (aka “gerrymandering”) really go.

1. Why such a strange word?

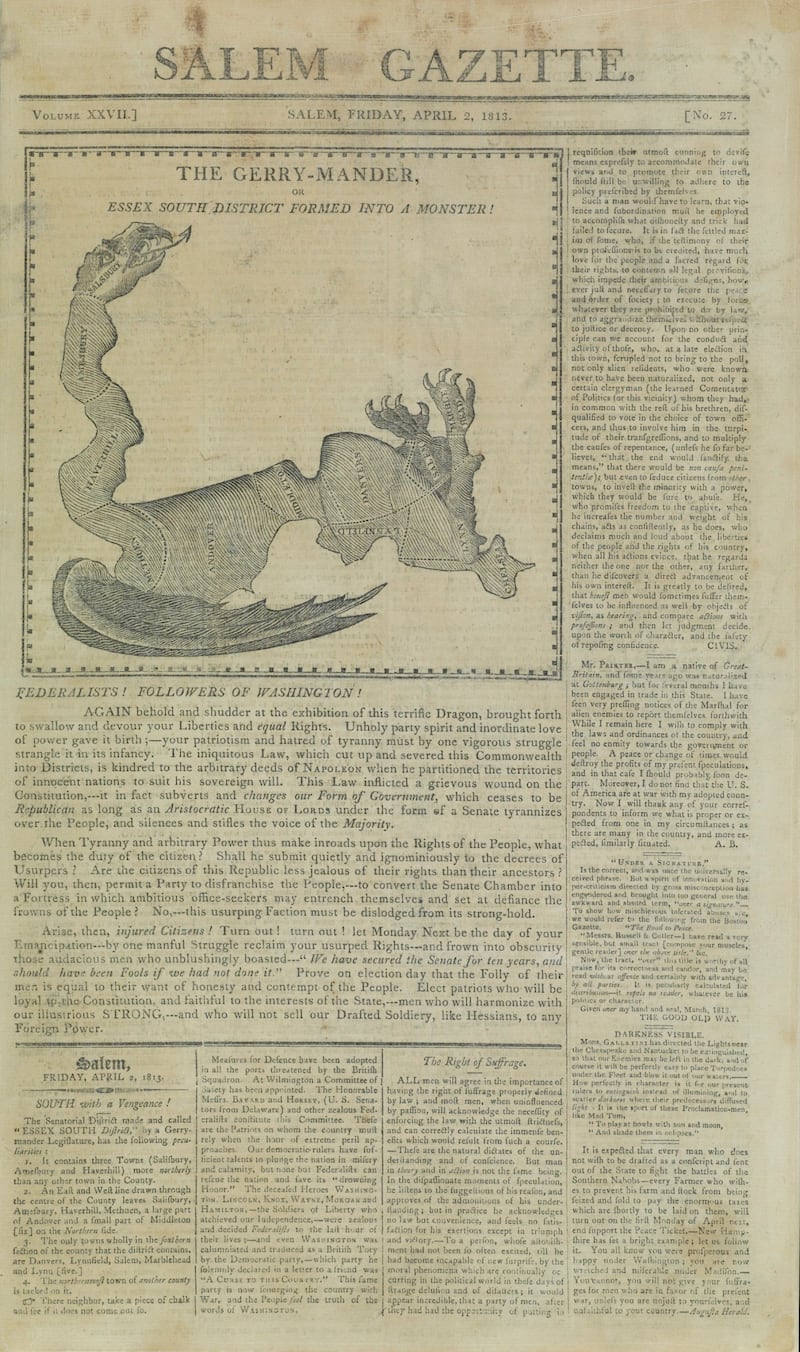

In 1812, Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry — a signer of the Declaration of Independence — signed a bill that redrew the state senate election districts to benefit his Democratic-Republican Party.

One district in particular was shaped so strangely that critics said it looked like a salamander. After a political cartoonist exaggerated the resemblance in a famous cartoon, the Boston Gazette dubbed it a “Gerry-mander.”

Opens in new window

Opens in new windowThis set a precedent as the first widely recognized manipulation of electoral boundaries for political gain.

2. Concerns of biased redistricting happen regularly

Rather than only an occasional occurrence, accusations of unfair redistricting have been a persistent and widespread battle throughout American history.

“Everybody manipulates the districts. They have done this since before the country was founded,” political scientist Jeremy Pope said in an interview with the Deseret News. Pope is a Constitutional Government Fellow at BYU’s Wheatley Institute and a political science professor.

It’s especially when census data comes in every 10 years that every state in the union redraws electoral maps to some degree. This happens for both the state house and senate, as well as the boundaries to elect U.S. House representatives — representing at least 150 redistricting opportunities every 10 years.

What’s unique about Texas is this is happening in 2025 — not immediately following a census. The state also featured the other most famous example of “mid-decade redistricting” when Texas Republicans, led by then-U.S. House Majority Leader Tom DeLay, redrew the congressional districts in 2003, in order to shift the U.S. House delegation in favor of Republicans.

Though such “off-year” redistricting is technically legal, Joshua Ryan, political scientist at Utah State University, tells Deseret News he considers it “a violation of institutional norms and practices.” That may be one reason why, despite gerrymandering occurring throughout U.S. history, Ryan says it has “only become highly controversial in the last few redistricting cycles (i.e., since about 2000).”

Texas, however, is hardly alone in taking controversial action. In the 2020–21 redistricting cycle, over half of all U.S. congressional maps were accused of being gerrymandered — with several lawsuits resulting.

3. Accusations of gerrymandering happen more in states controlled by one party

Gerrymandering accusations are more common when one party controls the process. There are 38 states where one party controls all levers of government (23 Republican states and 15 Democratic states).

At least 28 out of the 38 states with unified party control have experienced gerrymandering accusations through court challenges in the last decade (61 cases challenge Republican-drawn maps, while 11 challenge Democratic-drawn maps).

For instance, Maryland and Illinois are widely seen as sites of forceful gerrymandering by Democrats. And after Utah voters passed a proposition establishing an independent redistricting, the state Legislature passed a bill stripping that commission of its enforcement ban — effectively returning redistricting control to itself. A subsequent 2021 redistricting map divided Salt Lake County in a way many Democrats especially saw as gerrymandered.

4. So, why don’t courts intervene?

They often do. For instance, the Pennsylvanian State Supreme Court in 2018 threw out gerrymandered redistricting in the state. And the Utah State supreme court ruled unanimously in 2024 that the state Legislature overstepped its authority, remanding the case to lower courts for consideration. Further rulings are expected in district court ahead of the 2026 midterm elections — with potential redrawn maps in Utah’s future.

There are dozens of other federal and state court rulings that highlight gerrymander concerns. Yet in Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 decision that federal courts cannot strike down maps just because they unfairly favor a party. Chief Justice Roberts called this a “political question” outside the reach of the judiciary — leaving this issue to the states or Congress to solve.

At the same time, courts have consistently ruled that using race as a dominant factor in redistricting violates the Equal Protection Clause (14th Amendment). That includes Shaw v. Reno (1993) that ruled racial gerrymandering was unconstitutional.

The exception to this are majority-minority districts designed to give minority voters an equal opportunity to elect preferred candidates. When states take steps to change or “dilute” such districting, courts have stood in their way. For instance, in Allen v. Milligan (2023), the Supreme Court struck down Alabama’s new congressional map seen as diluting voting power in the state’s Black community.

5. Attacks on gerrymandering are also politically advantageous

Pope of BYU said that political leaders often “talk about gerrymandering because it is preferable to attack the system rather than admit that if you really wanted to make electoral gains you would need to change something about your set of ideological issue positions or the candidates you run.”

Attacking the system can also stir up voters and galvanize one’s base.

“Both parties use gerrymandering and then complain about the other party doing it. ... This time there is a concerning added wrinkle: gerrymandering at the behest of a president,” Kelly Patterson, a senior research fellow with BYU’s Center for the Study of Elections Democracy, said.

“Midterm elections have often been barometers of a president’s performance,” he said. “Seeking to make the president even less accountable for any unpopularity seems like a troubling development.”

6. Does gerrymandering happen in other countries?

Although gerrymandering has the longest, most documented history in the United States, it shows up in other countries as well. For instance, before 19th century reforms in the United Kingdom, there were problems with “rotten boroughs” historically — that is, tiny populations with outsized representation.

Critics in Singapore have argued that electoral boundaries are changed without transparency, often benefiting the ruling party. And Malaysia has been highlighted as an example of aggressive gerrymandering since 1958, as the ruling coalition used redistricting to stay in power until 2018. Likewise, the Hazara ethnic minority in Pakistan has experienced disproportionate underrepresentation due to moves widely seen as boundary manipulation.

Other largely democratic places where gerrymandering has played a role, include Hungary, Kenya, South Africa and Sri Lanka.

7. Are there solutions?

In the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia, redistricting is done by independent commissions to draw electoral districts — with strong guidelines that ensure equal representation, so modern gerrymandering is rare.

Likewise, seven states have redistricting commissions that are considered truly independent — meaning, not controlled by politicians and designed to be nonpartisan or citizen-led. That includes Arizona, California, Colorado, Michigan, Montana, Idaho, Washington.

In 33 other states, redistricting is left entirely to the state legislature. In still another 10 states, including Utah, attempts at additional balance have included advisory committees appointed by legislatures or political parties.