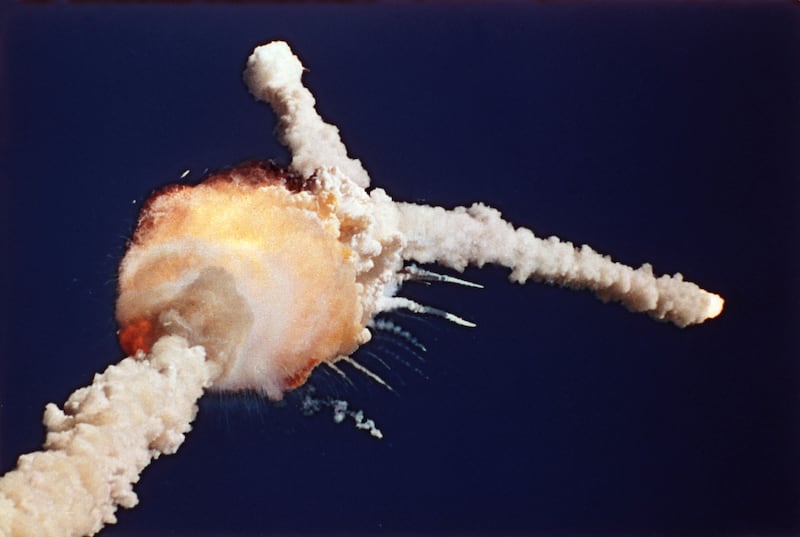

Forty years ago today, Jan, 28, 1986, classrooms and households alike watched a live broadcast of what they thought was going to be a happy historic day. However, 73 seconds after launch, a rocket on the NASA Challenger’s booster exploded in the air, and all seven individuals on board the shuttle lost their lives. Included in the deaths was Christa McAuliffe, who was supposed to be the first American schoolteacher in space.

McAuliffe was advertised to the country as an example that anyone can achieve their dreams — even average Americans as people all over the country tuned in to watch the special occasion take place live.

Unusually cold weather in Florida led to one of the largest symbols of tragedy still etched in the minds of Americans old enough to remember. The cold weather caused an O-ring, which formed a seal between rocket booster sections, to lose its elasticity. Later investigations, found this faulty O-ring formed a leak, leading to a flame, which caused the gas tank to heat up and explode.

According to Richard Feynman, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist who served on the Rogers Commission — the commission that investigated the tragic event — the accident didn’t have to happen.

“It was an accident that had many, many warnings that there was something wrong and that it might sooner or later go off,” Feynman said. “The warnings were disregarded.”

According to The New York Times, William Lucas was told engineers felt the launch should be delayed due to the cold weather and the fear of leaking O-rings. Lucas did not pass the warning to higher-ups, saying that it was not part of the reporting channel.

Roger Boisjoly, an engineer at Utah-based Morton Thiokol, had raised serious concerns about the O-rings’ performance in cold weather and worried about the disaster that could happen.

“The result would be a catastrophe of the highest order — loss of human life,” he wrote in a memo a year before the tragedy.

In the days leading up to the launch, Boisjoly warned once again of the danger and wanted to postpone the flight because of the predicted cold weather. But his request was denied. Later on he received awards from the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers for trying to halt the Space Shuttle Challenger launch.

Boisjoly died in 2012 in Nephi, Utah.

The gravity of Boisjoly’s unheeded warnings were emphasized by the findings of the Rogers Commission, where Feynman played a pivotal role.

Feynman’s insights were instrumental in highlighting the critical oversight in NASA’s management of engineering concerns. The commission’s investigation ultimately spurred a complete overhaul of NASA’s safety and risk assessment protocols, aiming to prevent such tragic oversights in the future.

How NASA fared since then?

As American perception of NASA plummeted, NASA needed to respond. Following the investigation, the space organization made over 100 adjustments to shuttles and also changed its internal culture, Robert Cabana, former NASA astronaut and director of the Kennedy Space Center told CNN.

“We could have prevented that from happening,” Cabana said. “That’s why it’s really important that we always, always ask questions and listen.”

Today, NASA continues to grow and learn as it finds new discoveries in outer space.

About the Challenger crew

Aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger were seven crew members: Francis Scobee, commander; Michael Smith, pilot; Ronald McNair; Ellison Onizuka; Judith Resnik; Gregory Jarvis; and McAuliffe, the teacher.

It wasn’t until Sep. 29, 1988, when NASA launched its first mission following the Challenger disaster.