SALT LAKE CITY

They came to Salt Lake on the run. The place they left insisted they couldn’t legally leave. Their financial rating was down there with junk bonds. And by the way, New Orleans wanted its nickname back.

When the Utah Jazz played their first game in Salt Lake City 40 years ago, they had all the credibility of a penny stock salesman.

Now look at them.

* * *

Dave Fredman remembers.

Fredman is the lone full-time employee remaining from that first Jazz iteration that came to Utah in 1979. He remembers the threats of lawsuits that kept the NBA from letting the team leave New Orleans until June that summer; he remembers the Jazz’s trainer, Don “Sparky” Sparks, spiriting the team’s equipment out of the SuperDome in the dead of night; he remembers rolling into town at age 26 as head – and sole member – of the PR department, part of a front office that “I know was under 20 people, counting the coaches.”

He also recalls not being particularly worried that somehow they’d make it.

One, “because I was young and didn’t know any better,” and two, because leading the small band of less than 20 was a fast-talking, wise-cracking New Yorker who could sell snow cones – and the machines that made them – to Eskimos.

Surely Frank Layden, the franchise’s general manager, could sell NBA b-ball to Salt Lake City.

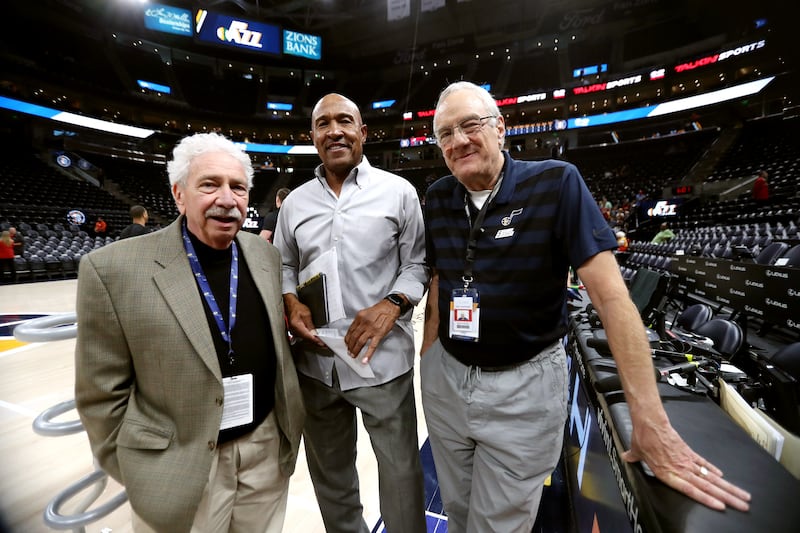

“Frank was optimistic. Frank was positive. Frank was Frank,” says Fredman, now the Jazz’s director of pro player personnel.

Frank was also realistic.

“He used to pull me aside and tell me, ‘We’re going to have a winning team,’” says Fredman. “‘Let’s just hope we’re still working here when it happens.’”

Ask Fredman to list those things he’s most proud of in his long tenure with the Jazz (he once left briefly to work for the Denver Nuggets), and he starts with, “Well, first, I was responsible for Dan Roberts. I’ll always be proud of that.”

Roberts is another person who can trace his Jazz employ all the way back to opening night on Oct. 15, 1979. (John Allen, Will Arnott and Ron Beck of the stat crew can also make that claim).

Dan “How about this Jazz” Roberts was the P.A. announcer 40 years ago, he’ll be the P.A. announcer for this Wednesday’s home and season opener, and plans on being the P.A. announcer as long as he can talk.

After emerging as the winner of Fredman’s auditions in ‘79, Roberts remembers being so thrilled to get to announce NBA basketball that he never stopped to concern himself over whether it would survive. It helped that Roberts had been the courtside announcer for the famous Larry Bird-Magic Johnson Final Four at the University of Utah earlier in the spring of 1979 and that he worked for the Utah Stars when they won the American Basketball Association title in 1971. If Roberts was sure of anything, he was sure Salt Lake was a good basketball town.

Which brings us to the third person who was there when the Jazz and Salt Lake City got married and is still an integral face of the franchise.

Actually, Ron Boone wasn’t technically there at the beginning. Boone was traded to the Jazz from the Los Angeles Lakers 13 days into the 1979-80 season. He played his first game in a Jazz uniform on Oct. 27, 1979, scoring 14 points. He never missed a game until he retired the next season, leaving behind a 13-year career in the ABA and NBA that included 1,401 consecutive games, still the second-longest ironman streak in professional basketball.

After returning to his native Nebraska in 1981, Boone came back to Salt Lake in 1988 to join the Jazz broadcast team. He’s been a color commentator on TV or radio for the past 31 years.

Like Roberts, Boone, who was a key player for the Utah Stars team that won the ABA championship, had seen the way Salt Lake could treat pro basketball.

“I thought the Jazz would survive strictly from my experience playing with the Stars,” he says.

“We could see it wasn’t going to be easy,” he adds, reflecting back on a cash-strapped franchise operating on a shoestring budget. “We could see how hard it was to win NBA basketball games. We had good talent, we needed great talent.”

* * *

Roberts has a good memory. Reflecting back to the home opener 40 years ago, he says, “As I recall we got the crap kicked out of us by Milwaukee (correct, a 131-107 loss), there were about 7,800 people (7,721 to be exact, in a Salt Palace arena that held 12,616), and the Osmonds sang the anthem (also correct).”

I had to go back to the Oct. 16, 1979, edition of the Deseret News to jog my memory. As a sports columnist sitting courtside for the home opener in the Salt Palace, I filed a column chronicling NBA firsts – Pete Maravich made the first shot, Kent Benson had the first miss and the first dunk, Big John Sudbury talked the first trash – and noted that everyone at the game was given an “I was There” certificate, verifying their attendance at the first NBA game played in Utah.

“Could be worth some money one day,” I wrote. “If the crowds pick up and the franchise stays.”

I don’t know where that certificate is. Maybe it’s lost. Maybe if I dug around in some old boxes I might find it. Although even 40 years later, I doubt it would be worth anything.

But as the projected sellout for Wednesday’s opener illustrates, the crowds did pick up, and the franchise – worth $1.4 billion according to Forbes – definitely stayed.

“However you look at it, it is an amazing story,” says Fredman. “I don’t mean to sound corny, but I consider it a blessed life just to be able to see where it was and where we’ve been able to go – from an opening night crowd of 7,700 and look at it now. It’s a great feeling to know that the blood, sweat and tears everyone put in has paid off.”