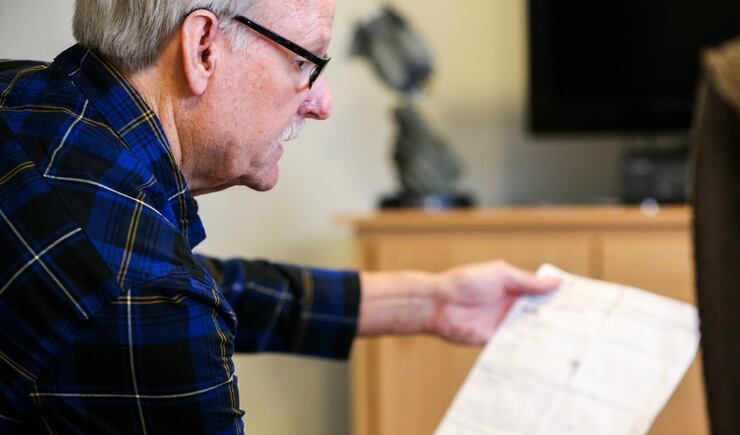

SALT LAKE CITY — A mixup at the rental truck counter could have made a felon out of a Sandy grandfather.

He arrived late to pick up a trailer in July, he said, but a clerk allowed him to tow it away anyway. Moments later, police pulled up to his home. The equipment had been reported stolen.

“What have I done?” the grandfather, Eugene, recalled asking. “This is my first encounter with the police in 70 years.”

He qualified for a second chance under a new program in Salt Lake County. Prosecutors would drop the case and forgo filing formal charges if he took six hourlong classes, checked in with a case manager regularly and kept his record clean.

“We need to be careful about how prosecutors are using their discretion when they’re screening cases. We should be tracking whether certain demographics are more likely to get diversion over others.” — Jason Groth

Utah has long given similar second chances to veterans and offenders with mental illness or addictions who have already been charged. Now, top law enforcers in the state’s two biggest counties are offering a diversion program to first-time offenders before ever indicting them.

A retiree who spent his earlier career developing printers, Eugene asked the Deseret News to withhold his last name as he hunts for a new job. While he believed he had had a strong defense in his criminal case, a recent divorce took a toll on his finances, he said.

“So I had two choices: Either go spend the money for good representation, or go to a free class for six days and get something out of it,” Eugene said. “I had to look at it in a logical, analytical way, and look at it as the least of two evils.”

***

Most states offer the programs, which proponents say help relieve an overburdened criminal justice system and address the causes of a person’s misconduct. Critics have said they sometimes grant prosecutors too much authority.

“No one in America should have power that an elected prosecutor has. But that’s where our system is,” said Utah County Attorney David Leavitt, a Republican in his first term. “Ninety-nine percent of the time, I’m going to give a plea bargain after we file. Let’s give these people a chance before we file, and then everyone wins.”

“What have I done? This is my first encounter with the police in 70 years.” — Eugene

Half of the caseload in the Utah County office is low-level drug offenses, many with no history of theft or violence, Leavitt said. It means other types of important cases on his attorneys’ desks are not getting enough attention, like elder abuse, failure to pay child support, sexual assault and fraud.

Leavitt was on the freeway headed to a Tabernacle Choir rehearsal last year when the idea for the program struck him, he said. He had long believed jail time is not the most detrimental penalty for offenders.

“The worst punishment we give is the label of being a criminal, because that affects them for the rest of their life,” he said.

Leavitt and Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill, a Democrat, envision the alternate plan as a stepping stone toward broader reforms in the state’s criminal justice system.

Not everyone is eligible, however. Those accused of DUI and violent or sexual offenses don’t qualify. A person must have few prior convictions, if any.

And the programs are starting small. About 50 have signed on to participate in Utah County and roughly 30 in Salt Lake County since they took effect this summer. Both leaders said they try to analyze how well the new approaches work and scale them up in the future.

Prime candidates for the Salt Lake program are a 19-year-old who deals a small amount of marijuana to a friend for the first time, or a caretaker who steals money from a vulnerable person and needs coaching on how to manage stress, said Gill.

“Often they’re there categorized as low-risk and often low-need, but they’re engaging in the justice system. We don’t need to waste the resources. We don’t need the conviction,” Gill said. If only 10% of people graduate the program, he added, “that is a systemic win. That’s a workload win for us.”

In Utah County, many are 18 or 19 years old and have no prior history with police, said Sherry Ragan, the deputy county attorney overseeing the program there.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Utah, which has called for greater scrutiny of prosecutors, believes the alternatives to jail and prison are generally a good thing. But failing to pay fees should not flunk a person out of the program, said Jason Groth, the ACLU’s smart justice coordinator.

“We need to be careful about how prosecutors are using their discretion when they’re screening cases,” Groth said. “We should be tracking whether certain demographics are more likely to get diversion over others,” including people who are white or those who can afford it, he continued.

Greater numbers of minorities in the U.S. face marijuana-related charges, he added, so precluding someone from participating based on prior drug arrests could reinforce existing racial bias in the criminal justice system.

In Utah County, a private probation company will oversee participants, charging a monthly $35 or a sliding scale fee. Prosecutors there consult victims and investigators before offering the second chance, and may require community service or repayment for any damage or loss.

“We’re really trying to keep the cost down for them,” Ragan said. She noted they would likely fork over more in court fines if convicted.

The process can take up to a year in Utah County and six months in Salt Lake before a person receives a formal letter declining to prosecute them.

The Salt Lake program, administered by the county, is free yet available to fewer: a person can’t have what the office has deemed a substantial history of substance abuse, a medium to high risk of reoffending or owe restitution.

Those groups can qualify for an existing process that Gill says will be expanded, allowing some to have charges dismissed after completing requirements and others to eventually have a conviction reduced.

***

Eugene, who faced the rental truck felony charge, said he took home tips from his required classes on how to better communicate with others and read body language. Journaling exercises helped him reflect on the opportunity to maintain his sparkling record.

“I did keep an open mind and I did learn a few things I had never thought about, to be honest. And so I did get something positive,” he said.

Still, he said he can’t shake the feeling an impartial authority would see his case the way he does: a verbal agreement that somehow went off the rails in a busy rental shop, where he said he had promised to return the truck in time for the next renter and the clerk clearly agreed.

But before he could pack the trailer to haul belongings to his new apartment, he was handcuffed and placed in the back of a patrol car.

He later called the shop about the mixup, wishing he had drawn up a written agreement that day before the clerk began helping others. The representative on the other end of the line insisted they’d had no deal, he said.

Some judges in other states, dissatisfied with the tack prosecutors took, have started up their own programs. No such version exists in the Beehive State.

Eugene said he wasn’t sure if he might qualify for a public defender.

“it’s a possibility, but I didn’t want to take the chance,” he said. “I’d much rather go ahead and kind of swallow the bitter apple and take six hours of my time.”