SALT LAKE CITY — Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill won’t file criminal charges against a Murray officer who shot a woman after she fired a round from inside her home, saying the case is tied to a “systemic breakdown” in services for Utah’s mentally ill that results in dangerous encounters with police.

“It’s a public health issue,” Gill said in a news conference at his Salt Lake City office on Friday. “It should not be a criminal justice issue.”

An emphatic Gill estimated that more than 1 in 3 police shootings he reviews are tied to a person’s mental illness or cognitive disability. But a measure to address the issue has stalled at the state Capitol for several years, he said.

On March 5, Murray detective Bradley Rowe shot Rhonda Lee St. Onge, 58, once in her lower left abdomen, sending her to a hospital for treatment. He was one of four officers there; none were injured.

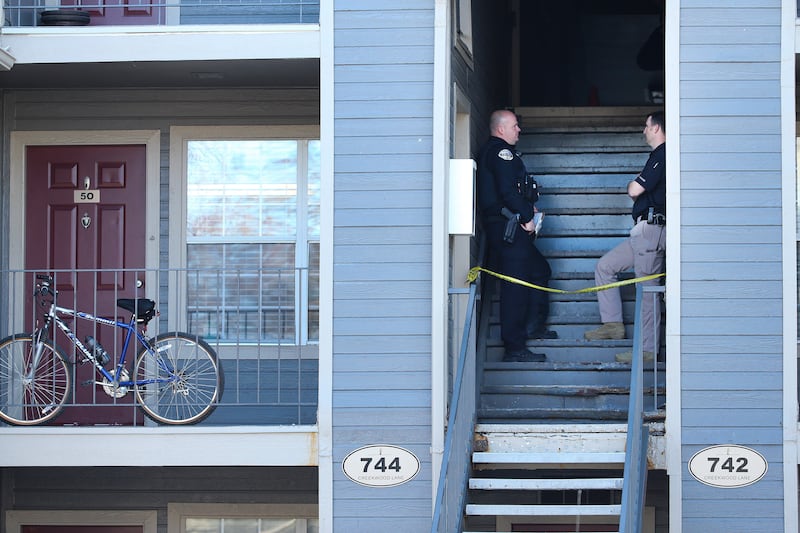

Police had accompanied a social worker to the Stillwater Apartments, 5560 S. Vine St., after neighbors reported seeing her waving a pistol while partially clothed, Gill said. Body camera footage shows the social worker knock on St. Onge’s front door before a loud bang is heard.

Although Rowe declined to participate in Gill’s investigation, other officers reported fearing the gunshot, which struck the top of St. Onge’s door frame, had injured St. Onge or someone else.

Police urged St. Onge to come to the door before using a property manager’s key to go inside. One officer’s body camera captured St. Onge standing and appearing to lean forward.

While Rowe’s colleagues reported she pointed a handgun toward them, no weapon is visible in the video before a single shot rings out.

Gill said a jury would likely find Rowe justified, noting another officer described St. Onge as in a “shooting stance.”

When police rush into the apartment, St. Onge is seen on the ground. Police handcuff her and ask “Are you hurt?” while noting there is blood on her shirt, indicating she was shot. She survived.

Gill said police recovered a silver handgun next to her on the floor and found two others in her home.

Gill declined to weigh in on whether officers could have taken other steps. But he spoke in favor of pending bills that would mandate crisis intervention training for officers and require classes in de-escalation, and said there are too few beds available at the Utah State Hospital due to a lack of funding.

A judge in August found St. Onge incompetent to stand trial, meaning she’s not capable of understanding the case against her or working with attorneys on a defense. She faces four counts of assault on a police officer, a second-degree felony, and aggravated assault and felony discharge of a firearm, both third-degree felonies.

Her case is still pending as doctors work with her to restore legal competency. But Gill noted that other defendants who cannot meet that threshold are released from the state’s custody and their cases closed, with several failing to connect to help or show up to civil commitment proceedings that would find them a place in the state psychiatric hospital.

Now Gill, a Democrat, is urging state lawmakers to pass a legislative proposal he says would create a program to ensure those Utahns stay on track with treatment and medication. He noted the measure did not get a hearing in the 2019 legislative session.

Gill said St. Onge, who was on the radar of Adult Protective Services — the state agency that sent the social worker — represents the “healthiest experience within the system.”

Her attorney, Michael Colby, did not immediately respond to a request for comment Friday.