In a matter of weeks, a virus changed everything.

It was the kind of change that leaves people feeling fragile, their lives unscripted. The kind that triggers a double take at power and powerlessness. It was the kind of change that requires people to look one another right in the eyes.

At first, the headlines comforted and reassured.

Then came a statewide shutdown.

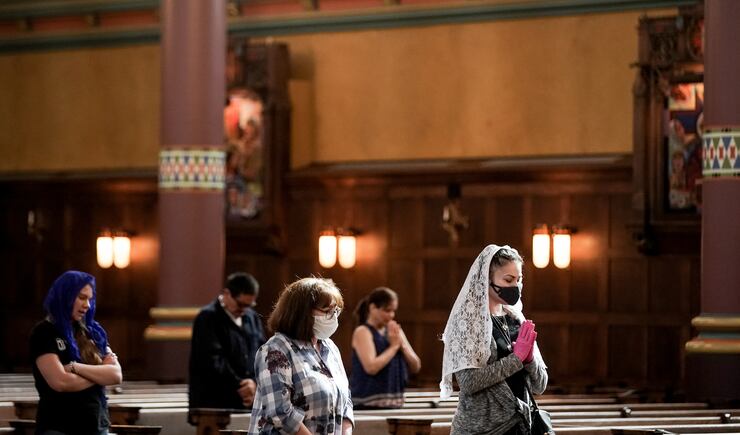

Soon masks concealed people’s faces, leaving only the window to the soul.

It was 1918. The virus, though it wouldn’t be identified as a virus until the 1930s, was influenza. And it was spreading over the land, the Deseret Evening News warned.

A portrait of Utah was painted in news ink: the fearful and the undaunted, the educated and the ignorant, the risk-averse and the risk-taker, and everyone in between.

Radio news was still a few years away, so newspapers were in their heyday as bastions of community thought. Dozens of publications, most long since laid to rest, covered the state. Reporters kept their typewriter keys pressed against the pulse of public opinion, testing their power to both reflect and shape it.

The most potent weapon in the battle for the health of Utah, the Salt Lake Telegram said, was the “white light of publicity.”

An analysis of hundreds of archived articles at Utah Digital Newspapers shows the fraught course the state navigated through the fall of 1918. The headlines told stories of intense loss and ideological tension. Even the weather graphics seemed to foreshadow the travail. But amid the uncertainty, there was good humor.

“Masks are the vogue from this day forward,” the Ogden Daily Standard announced on Oct. 17, 1918. “If their effect on your handsome countenance is to make you homely, then homely be the word and homely be the deed. To look homely under the present circumstances is the demand of patriotism.”

Utah knew something of masks and patriotism.

The public had been contributing to the production of gas masks for World War I amid the advent of chemical warfare. Soldiers wore the masks to neutralize poisonous fumes.

Back home, it was regular Utahns wearing masks. Only they were gauze masks, soft and light. And rather than trapping the wartime wafting of chlorine gas released by a tactical enemy, they were trapping droplets released by their own shouts and laughs, whose peaceful passing into their loved ones’ lungs could cause suffering they wouldn’t wish on their worst enemy.

Reporters used the war metaphor to inject patriotic ink into the vein of public discourse. They wrote in terms of duty, battles and victory.

“With the flu germ in the air, you cannot always detect the strategy of the enemy,” the Telegram said.

Homely. Homebound. A homeland grappling with the whiplash from one crisis to the next would be given only a short time to wake up to this new war.

A short time

The news swept across the Wasatch Front as readers picked up their evening newspapers on Oct. 9, 1918: “Drastic order effective immediately.”

“Salt Lake City will be schoolless, churchless, and amusementless after tonight,” wrote the Salt Lake Telegram.

For the first time in history, the Utah State Board of Health had ordered a statewide shutdown to fight the growing spread of an infectious disease.

Only two weeks before, headlines had soothed — “Flu has missed Salt Lake as yet.” The problems appeared to be far away in other states. Even the Telegram’s weather forecast recorded the same phrase for seven days — “not much change.”

But the first 10 cases were discovered in the capital city on Oct. 3, and as the sky gave way to rain, the case count rose, reaching 350 by the board meeting six days later. Thirty patients at the University of Utah had already been moved to the Fort Douglas pest house, the building set aside to isolate the sick. Ogden was reporting almost 200 cases. In two more days there would be 1,200 statewide.

The Deseret Evening News reported the surgeon general’s message out of Washington: “There is no way to put a nationwide closing order into effect. I hope that those having the proper authority will close all public gathering places if their community is threatened.”

The board was decisive: Shut it down. No school, church, public funerals or large weddings. No picture shows, theater, pool halls or dance halls. No crowd-attracting sales at the department stores.

Newspapers that printed in the evening got the scoop. Big morning papers ran the story the next day and the small-town papers soon after.

White light, black ink

The Salt Lake Tribune ran “Drastic action” at the top of the front page. Adjacent was a professorial image of Dr. Theodore B. Beatty, the state health commissioner and driving force behind the shutdown, gazing stoically from behind his eyeglasses, hair combed slickly away from a center part.

The Salt Lake Herald-Republican ran “Utah bans all meetings” at the bottom of the front page. Adjacent was the newspaper’s own ill-informed opinion — “Epidemic is not serious” — an editorial, equally matched in headline size and shape so as to be the news article’s perfect companion piece.

“It may have been wisdom to close the churches and theatres, although we doubt it,” the Herald-Republican said. “There should be no more forecasts of mortality which serve only to make well people quite sure they are sick.”

There it was — almost as swift as the shutdown itself — the counterblast. No policy was beyond the reach of grievance.

The Eureka Reporter deemed the ban uncalled for and said the state had taken “hysterical action.”

The Ogden Daily Standard supported the shutdown but called out state officials, saying they should have taken action earlier, and accusing them of waiting until after the general conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which had been held Oct. 4-6.

“Was the state board of health more concerned over the dollars which were to flow into the capital than the possibility of a spread of the epidemic?” the Standard’s editor wrote.

The Richfield Reaper seemed wide-eyed at what it called “the greatest and most far- reaching health order ever issued in Utah,” but at once said the move would likely help a great deal, considering the many people who had been “lulled into a sense of security.”

Lulling or leading

Beatty’s stoic image quickly became the face of the state’s influenza response. He had built a reputation of authority as a warrior for vaccination during the smallpox outbreaks of the early 1900s.

Beatty was known for his fiery, eloquent orations in defense of public health and in the face of burning opposition. With the statewide shutdown, he sealed his place in the historical record.

“I was the best damned man in the state of Utah when we imposed the ban, and I made up my mind that I would be more heatedly damned still on the day that the ban was lifted,” he told the Standard.

Beatty was relentless in his fight against complacency and misinformation.

“Don’t be misled,” he warned the public.

Beatty had his eye on Dr. Woods Hutchinson, a noted physician-author, whose writings had attracted attention around the nation, and who was quoted in all the newspapers during his visit to Utah.

Beatty thought Hutchinson was a sensationalist, not a medical professional.

Hutchinson had downplayed the flu, saying he saw little benefit to the shutdown because there was no stopping the disease until it had run its course among susceptible people.

The papers published Beatty’s takedown: “It is no less than criminal to promulgate the unfounded and grotesque notion that notwithstanding all precautions, certain individuals are foreordained to have the disease or to die from it, these persons being those who are susceptible and therefore cannot escape,” he said.

Beatty’s orders, repudiations and advice were inked across every newspaper in the state, day after day.

Practice good hygiene, he said. Isolate when sick. Avoid public gatherings. Wear a mask, he said.

The gauze rooms

Mystic. Muzzle. Flip flu fashion.

The very sight of the medical mask led to lively language in newspapers.

“If a bevy of mysteriously veiled maidens scurries past you ... it will not be the Turkish harem,” the Telegram said, “but the female ranks of your own native city seeking ... protection from the deadly flu bug.”

The Red Cross rallied the female ranks to sew thousands of masks for front-line workers. A call went out to women everywhere, especially teachers, whose schedules were freed by the shutdown, to work in the “gauze rooms.”

Take a piece of gauze, 18 by 24 inches, the instructions began, and fold it into eight layers.

Six days a week, women cycled in and out of Amelia’s Palace, a downtown mansion made into Red Cross headquarters. A satellite operation was in full swing on the fifth floor of First National Bank in Ogden.

The great protectors of the sick — the ones whose backs bore the heaviest burden of caregiving, whose feet bore the weight of round-the-clock vigil, whose hearts bore witness to the suffering — were the women of Utah.

When the Red Cross pleaded day after day for nurses to fill shortages, they were pleading for women.

“Their work is not spectacular,” one writer said. “It is merely doing a thousand normal things.”

And when the women scrubbed a thousand sheets, and fed a thousand mouths, and checked a thousand heartbeats, and dabbed a thousand foreheads during the watches of the night — when they silenced a thousand thoughts of their own safety — it wasn’t spectacular, it was sacred.

Patriotic women, they called them.

“And many of them are said to be on the verge of collapse,” reported the Tribune. An overwhelmed nursing system simply needed people to stop getting sick.

Virtue in the masks

It didn’t take long before the conversation on masks shifted to the public at large.

“With schools closed, theaters banned and churches locked, the people continue to mingle in the streets,” wrote the Ogden Daily Standard. “How is the spread of the disease to be checked unless we resort to the general wearing of the light gauze masks, which but little inconvenience the wearer? The great virtue in the masks ... is the prevention of open sneezing which, when not obstructed, blows the germs into the air.”

Six days into the shutdown, the city of Bingham Canyon, which no longer exists, became the first city to institute a mask mandate. Provo followed four days later, with other cities in tow.

In cities without a mandate, businesses led the way. Reporters noticed sales clerks wearing masks at ZCMI. Traders at the stock exchange wore masks, knowing “the deadly little influenza microbes take a joy ride” from the mouth of a shouting man. Walker’s Beauty Parlor pledged, “Gauze masks worn by all our operators.”

The Salt Lake Telegram ran a picture of an army of newsies, or paper boys, all masked up. The boys were dubious at first, the article said, but “after a few minutes’ trial they were convinced that they could holler just as loud with the masks on as they have without them.”

Some Utahns joked they would no longer have to shave or wash their faces.

“And to those who know the local Navy men and appreciate manly beauty, the use of the masks will seem somewhat like dimming a candle under a bushel,” one writer quipped.

It was all in the eyes.

Laughing eyes, then tired eyes. Just tired. Nothing left but eyes.

The public health power of the mask was what it concealed. But its lasting power, the kind that could last 100 years, was what it revealed — total interdependence.

They were free individuals, free Americans, living out their existence in whatever way they saw fit. They had fought a war to be free. They were fighting World War I to affirm that freedom. Yet in the war against influenza, they were utterly reliant on one another down to their very breath. One person’s actions in the name of freedom could imprison another person in a hospital bed.

Freedom from infection, Beatty said, required people to see their duty to the public. “Unselfishness baffles influenza,” another health official said.

Behind the eyes was fear that if they didn’t do enough, lives would be lost — fear that if they did too much, a way of life would be lost.

Bad blood, foul air

By Oct. 24, there were 138 towns reporting outbreaks. The Red Cross estimated 20,000 cases of influenza across the state. The weather forecast warned of a frost.

There was talk of a statewide mask mandate. Any day now, the papers speculated.

The Board of Health went back and forth, at one point almost issuing the order. But in the end, there would be no statewide mandate.

It was impractical and unenforceable, Beatty said, especially because mask-making materials were in short supply. He favored leaving the decision to local authorities.

“The public will be given the opportunity to wear the masks voluntarily,” he said. Nowhere was the debate fiercer than in Salt Lake City.

The county medical society held a meeting and called for a countywide mandate. Anti-maskers accused them of packing the room with pro-maskers. That led to a four-hour meeting attended by physicians, surgeons, businessmen, theater operators and local officials. This time, pro-maskers accused leaders of packing the room with anti-maskers.

“Bitterness crops out early in meeting,” the Tribune wrote.

The antis said masks were a breeding ground for germs. They worried the clouding of their eyeglasses would drive the germs to their eyes. They labeled masks a “menace” that perpetrated the rebreathing of foul air. They said masks wouldn’t slow the spread of influenza.

In the end, Salt Lake County passed a mask mandate for the whole county — excluding Salt Lake City.

Those who boarded streetcars downtown but then passed over the city line would be subject to arrest unless they put on a mask, county leaders said.

Cities around the state — Garland, Providence, Parowan, Cedar City, St. George — announced rigid enforcement of quarantine and masking orders, some threatening misdemeanors and arrest.

Ogden announced that any merchants who did not supply their clerks with masks would be arrested and vigorously prosecuted. Noncompliant barbers, store clerks and waitresses were fined $5.

In Salt Lake City and elsewhere, people were arrested for gathering to play pool, for hosting a dance inside a cafe, for congregating in the streets. The capital city hired 100 special officers to see that regulations were strictly enforced. Some argued the poor were fined while those with “bigger pockets were not being caught.”

Ogden and Park City tried to cut themselves off from Salt Lake’s outbreaks. They placed guards at roads and rail stations, requiring anyone entering the city to show a certificate of good health. Ephraim said the town marshal would meet travelers arriving at the depot and escort them home to quarantine.

The shutdown wore on.

Worn down

A week to 10 days, Beatty had guessed.

“It may be over very soon,” the Tribune had hoped.

“A little more patience and we will be able to go back to the normal way of living,” the Telegram had urged.

But going back to normal required having left it in the first place, and some Utahns weren’t awake to the fact that they were in a war. There was the “congregating upon the streets — night and day — of young people” and the “visiting about in the evenings, practically amounting to house parties.”

So the virus waged a war of attrition, sapping the public’s strength with continued losses. Douglas Earl, 33; Evelyn McCarty, 3; William Gray, 45; Betty Bradley, 6 months.

Salt Lake City alone logged 117 deaths in the first month.

Families were worn down. They were isolated, unable to gather and rejuvenate through worship or entertainment. Children were stuck at home without a quality education.

Industry was worn down. Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph lost 20% of its workforce and called for the public to eliminate all unnecessary telephoning. Utah Power and Light was losing $1,000 a day on streetcar operation. Layton Sugar Co. was searching for workers to fill gaps. The Western Conference postponed football games. Motormen and rail conductors, working up to 16 hours a day due to shortages, said they couldn’t change their masks or keep them clean, and if the mask order wasn’t lifted, they would strike.

Those tending the sick and deceased were worn down. At one point, every doctor in Brigham City was sick. Nursing shortages were near constant. One Ogden undertaker reported 12 bodies waiting for interment by 9 a.m.

The Deseret Evening News tried to find a silver lining: “The world will be much the richer and safer for the knowledge now being acquired, even though this is presently being purchased at a high and sorry price.”

A week into November, case counts seemed to dip, sparking talks of reopening soon — maybe Nov. 18.

Finally, Utah thought, the worst might be over. The weather was “generally fair.” The Nov. 5 election had drawn crowds of voters, but officials had set up outdoor polling tents where possible, encouraged masking, and ensured physical distancing.

Then came the Armistice.

Delirium and droplets

News that the war had ended sent people flooding into the streets on Nov. 11 in a “delirium of joy,” the Salt Lake Telegram reported. The restriction of previous weeks erupted in impromptu parades and marching bands and cheery bonfires. Salt Lake went “joy mad” and reported “monster” unmasked crowds. In Ogden alone, there were 3,000 people in the streets.

In a release of pent-up emotion, authority bowed to the will of the people, the Tribune said. “The great joy reigned uncontrolled and uncontrollable.”

It was as if, in that moment, the depth of grief and suppression could be quashed by the height of triumph and liberation. But if authority would bow to the people, a virus would not. So cities were showered in confetti — and the droplets from shouts and laughs.

Nov. 18 came and went with no hope for reopening.

Thanksgiving wouldn’t be the usual, wrote the Deseret Evening News: “The day in Utah is being observed quietly and without any spectacular features.” And yet, after all the suffering, it could be the most important Thanksgiving ever, the reporter said, “for the many blessings received, one of the greatest being peace on earth, good will to men.”

The uptick in case counts following the Armistice stretched the shutdown several weeks, until at eight weeks, the Board of Health said it had been among the longest in the nation.

Finally, the day came for the first phase of reopening, Dec. 8. The weather was “unsettled and colder,” and so was the public atmosphere.

The Herald-Republican praised the move. The Standard raised suspicion the state was pressured by business interests.

The Deseret Evening News was hesitant: “The universal hope is that this is not premature. No one of sense has found any fault with the severity of the restrictions imposed; if there has been any criticism, it has been for doing too little rather than too much.”

The reopening freed churches, theaters and business of all kinds. Some cities abandoned their mask orders. Schools, however, would have to wait for the new year, Beatty said.

Educators cried foul. Principals scrambled to make plans for opening schools on Saturdays and canceling spring holiday to make up for lost time.

“We are ready to open the schools almost on a moment’s notice,” said the superintendent in Salt Lake City. “Parents will have to cooperate with teachers more closely than they ever have done before.”

The superintendent in Ogden thought the school closures didn’t make sense. “The children will mingle as much out of school as in it,” he said.

But Beatty was concerned above all for the children’s safety. He was undeterred.

“He cannot convert me and I cannot convert him,” Beatty said. “So, in the language of Shakespeare, What’s the use?”

Dec. 8 was a Sunday. The newspapers were dotted with lists of religious services: “Church doors open wide again; thanks and praise to rise.”

But there was no praise in the Bingham Bulletin, whose criticism captured Beatty’s prophecy that he would be heatedly damned the day he lifted the ban.

State leaders “had the unmitigated gall to throw open the theaters,” wrote Bingham’s editor. “They also opened the churches as a camouflage for their sins.”

“And so it had come to be,” Beatty said.

To come

In the new year, each city’s public health orders came in spurts and stops as case counts fluctuated. The headlines became fewer and further between. Beatty’s name used up less ink.

The people slowly went back to enterprise and commerce. They regained independence — their interdependence fading as their health strengthened, fading until almost forgotten.

In the end, historians estimate, deaths were undercounted, and as many as 3,000 Utahns were likely whisked from this life. Their loved ones would never forget.

But there would be little trace of the incredible exercise of emergency public health power. The words would sit silently in the pages of Utah law, tweaked here and there, until some future generation would see their leaders take drastic action.

Perhaps they would think it was the greatest, most far-reaching order ever issued. Perhaps they would fear death, or loss of freedom, and damn their leaders.

But, perhaps, they would look one another right in the eyes and remember their interdependence.

If there were ever another year like 1918.