SALT LAKE CITY — It isn’t the fact that Ravell “Flash” Call is retiring that’s taken everyone around here by surprise. Ravell is about to turn 66, an age well beyond the “Use by” date for a news photographer, his profession for the past 41 1⁄2 years.

The job is not for the faint of heart or slow of foot. News photographers are routinely asked to carry heavy loads for long distances in difficult conditions while being bossed around by a reporter carrying nothing more than a pen and notebook. That’s the basic job description. They’re low-altitude Sherpas. Few last much past 60.

So chronologically it’s beyond time for Call to hang up the lens.

It’s just that no one thought he’d ever slow down long enough to actually do it.

* * *

The stories around the Deseret News are as legion as they are legendary: the lengths Ravell Call would go to get a photo. Whatever it takes was always his one and only game plan.

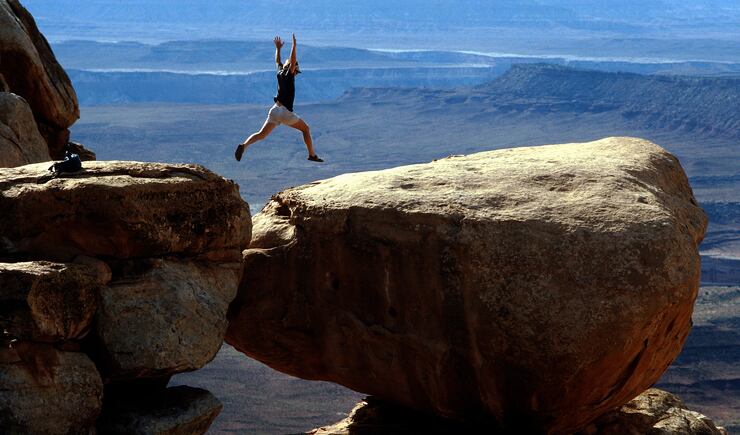

Like the time he was asked to shoot pictures of the window washers who dangle over the sides of high-story buildings and he dangled right along with them. Or the time the story was about BASE jumping and he climbed out on the ledge beside the jumper (Ravell was the one without the parachute). Or the time he was in El Salvador covering the aftermath of an earthquake when a policeman called out as he left his hotel, “Be careful out there, they like to shoot Americans.”

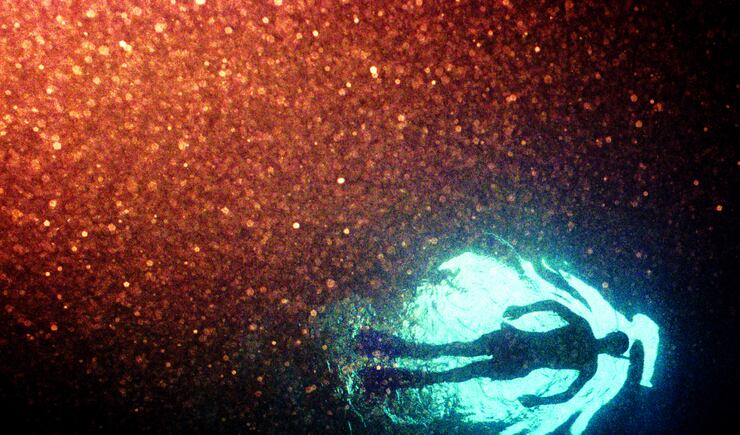

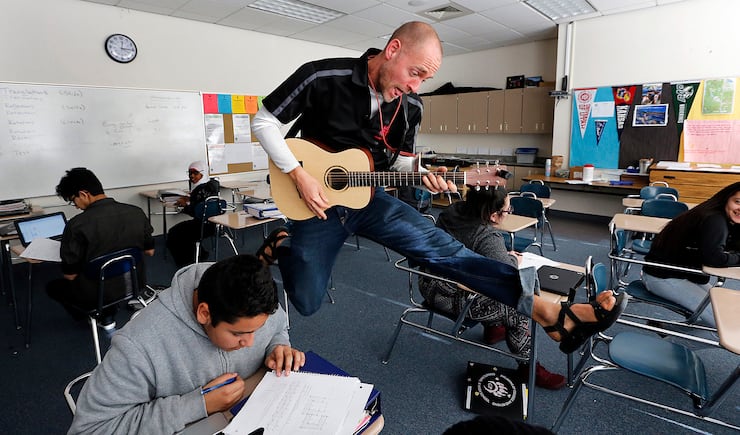

Reporter Marjorie Cortez reminisced about a story she and Call did together that illustrates his go-anywhere, do-anything approach to news photography: “When I was a business writer, I reported on a company that used an electron beam to sterilize medical equipment. The devices to be sterilized were placed in metal baskets that moved on a conveyor belt through a concrete chamber about 20 feet by 40 feet. Ravell felt his best photo was in the chamber, so next thing I knew, he had climbed INSIDE the chamber. It’s important to understand the unit was not operating at the time. It’s indicative of the lengths Flash would go to get his best shot.”

Tad Walch, the paper’s Latter-day Saint beat reporter, was on assignment in Samoa with Call when they spotted a mother walking her son home from preschool. Their story was about the preschool, and here, Call saw, was the perfect picture.

“Ravell wanted to get ahead of them to take their photo,” said Walch. “But he was the one driving and we were on the wrong (left) side of the road, something I had never done. I told him to pull ahead of the mother and son, and I would somehow manage to drive the car. But his internal shot clock was ticking and he said not to worry.

“He pulled over, hopped out, grabbed his gear and took off sprinting as best he could carrying his two cameras. The irony, of course, is that after running ahead of the mother and son over and over again for a couple of miles, the main shot that appeared with the story was one he took from behind.”

Sports writer Doug Robinson covered the U.S. Olympic Trials in Indianapolis one year with Call. He remembers Call running around the track setting up equipment and positioning for shots.

“And that was before the meet began. He set up a camera on the backstretch so he could take a remote. He had me holding some instrument, I don’t even know what it was, during the long jump competition. He was just a fanatic about getting the job done right; a true artiste, always running around doing something. Whenever I saw him I felt I had to look busy, because that’s what he does, he never stops. I don’t remember him sitting down that week. We shared a hotel room and I don’t think I ever saw him.”

The Deseret News sent writer/editor Jesse Hyde and Call to the Philippines after the typhoon of 2013. They slept on the floor of a half-destroyed building and rode in rickety boats for days on end as they chronicled the damage and the cleanup. But what stands out most for Hyde occurred in Manila just as they were getting started.

They were about to get on a boat to go to an outer island. “We stopped off at a kind of Philippine knock-off of McDonald’s to get something to eat,” said Hyde. “As we were eating, Ravell called this little boy over and gave him everything he had left of his meal. To me, it was indicative of the kind of guy Ravell is. You’re in a country reporting this crazy thing, everything’s in disarray, and he has the presence of mind to see this little boy who’s hungry and needs food and gives it to him. He’s the consummate professional, it’s true. He’ll do anything to get the story. But to me he’s also a very, very good dude.”

Scott Winterton wouldn’t argue with that sentiment. Winterton was a sixth grader when he met Call at a photography workshop. Call encouraged the young photography enthusiasts to reach out to him if they ever needed anything. When he got to high school, Winterton did just that, wondering if it might be possible to go on an assignment with Call and watch him work. True to his word, Call let Winterton tag him around on some assignments. At one of them, a shoot at the Great Salt Lake, Winterton snapped a picture of Call at work, developed the photo in his home darkroom, laminated it and carried it in his wallet all through high school.

“He was such an inspiration to me,” said Winterton, who in 1997 became Call’s colleague when he joined the Deseret News photo staff. “He never said, ‘Hey kid, go away.’ He was always so supportive. Just an exceptionally kind, fair-minded person. Not just to me. But to everyone.”

* * *

Tom Smart gave Call his nickname, Flash.

“It just fit. The Energizer Bunny has nothing on him,” said Smart, who retired in 2015 (when he was 62) after a long career working alongside Call at the Deseret News. Smart was named photo editor the year Call joined the News staff in 1984 and soon appointed Call as his assistant.

Photography wasn’t Call’s first career choice. The grades he got at Star Valley High School in his hometown of Afton, Wyoming, earned him a chemical engineering scholarship to BYU, where he started out as a math major.

Math was a solid major and engineering was a fine career path, but he found he had all this energy that needed an outlet. In high school he wrestled and ran track (the sprints, of course) — your basic one-man generator — and when he wasn’t doing that he was either skiing and riding motorcycles or thinking about skiing and riding motorcycles.

His life’s course changed when a friend at college showed him his photography equipment and talked to him about his goal of photographing wildlife for a living.

To Call, that sounded so much more active. He switched his major to communications with a photography emphasis, which is how he came to discover the wonderful world of news photography. Here was a career he could sink his teeth, and his energy, into.

“I found something that had excitement and variety every day,” he said. “It was more than a job, it was a way of life.”

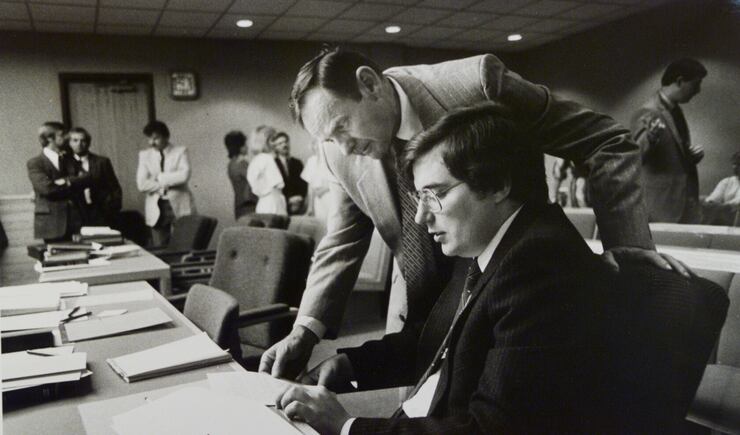

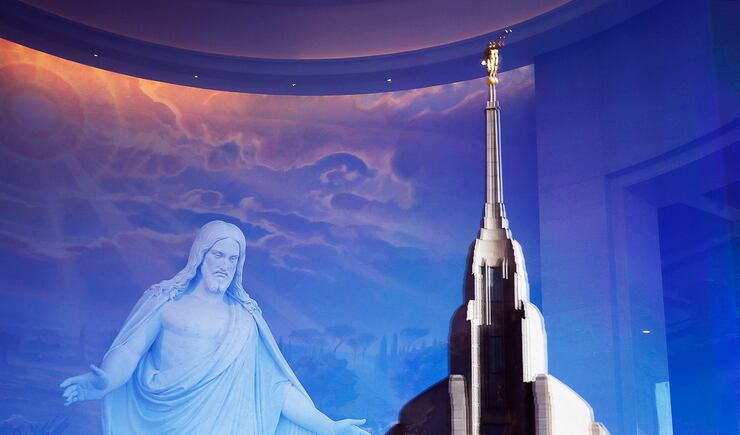

His first job out of BYU was in 1979 at the Sun-Advocate, a weekly newspaper in Price. A year and several photography awards later, the Salt Lake Tribune snapped him up. Four and a half years and another truckload of photo awards after that, the Deseret News had an opening. Call applied and got the job. In the process, he did something that isn’t likely to be replicated any time soon, if ever: On Saturday, Oct. 6, 1984, he shot general conference for the Tribune. On Sunday, Oct. 7, he shot general conference for the Deseret News.

The photo department had never seen anything quite like him. “You make me nervous,” Call remembers veteran photographer Gerald Silver saying after sizing him up. “You move around too much.”

But as soon as they realized the new guy only had the one gear — and he was as harmless as a friendly greyhound — everyone relaxed. Well, everyone but Call.

“He’s a guy that you’d have to order to stay home,” remembered Smart. “He’d get off his deathbed to come to work. I don’t think you could find a more loyal employee. And I’ve never met a more fastidious person in my entire life. He cares about details, he cares about making sure captions are right, he cares if names are spelled right, he cares about getting the shot, and what he really cares about are people.

“I think he stepped down (as manager of the photo department) when we had the massive layoffs (in 2010) because it was too painful for him to lay off his colleagues and friends. He was like, ‘I think I’m going to go back to shooting pictures and do what I love.’”

Chuck Wing, who took over as head of the Deseret News photo department in 2010, credits Call with “raising the bar for all of us. He took everything up a notch. On a personal level, I owe him a lot. He taught me so much about patience and kindness and caring and work ethic. About leadership.”

Call can’t quite believe how fast four-plus decades have flown by. Or, now that you mention it, that all of him is still here.

“I guess I’ve had my share of close calls,” he’ll concur, when pressed. Like the day he was shooting a fire in the Eagle Mountain area and he rented a helicopter to get up above the smoke for the most dramatic images.

“We had to take the door off to shoot pictures,” he remembered. “I’m just sitting there in the chopper, leaning out, I don’t know how many feet up, but a lot, and I looked down and the seat belt’s undone. I fastened it and looked down and it popped off again. I told the pilot. He said, ‘Yeah, we’ll have to put some duct tape on that next time.’ So that was interesting.”

His most memorable photos? One that comes to mind is the one he took of 7-foot-6 basketball star Shawn Bradley dancing at his high school prom with his date, who was standing on a chair. That one wound up in the national magazines.

Then there’s the one of Karl Malone dunking over Michael Jordan that Malone asked to have made into a poster.

A sad one is the one he shot of a pilot at an air show when the pilot was taking off — and he immediately crashed and died. “He flew it into the ground so he wouldn’t hit the crowds,” Call said.

His favorite photo of all is one he took with a timer of his family when the youngest child was a year old.

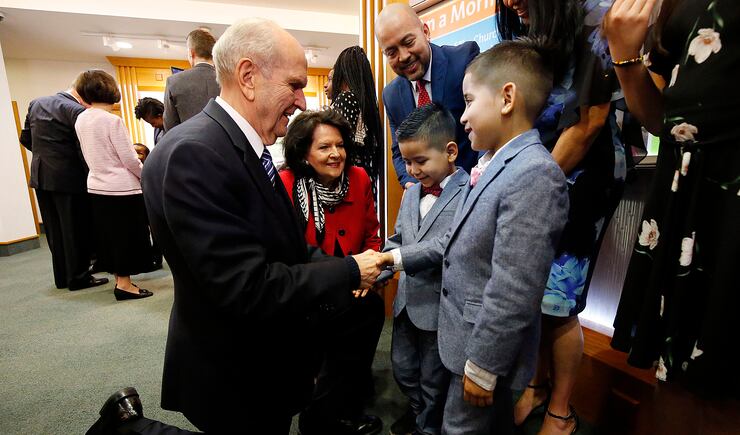

“I could not have imagined a better life,” he says. “What other job would allow me to rub elbows with celebrities and presidents, have the front row seat for the NBA Finals, the NCAA Final Four, the Olympics, to follow President (Russell M.) Nelson to Africa, England, New Zealand, Cambodia, Indonesia, Tonga and Samoa, to cover the aftermath of a typhoon in the Philippines, an earthquake in El Salvador, to make so many good friends and meet so many wonderful people?

And those are just a few of the highlights.

“With such a good job, why would I retire?” he begs the question.

“But photography is physically demanding,” he quickly answers before he can talk himself out of it. “My right knee, right ankle and right shoulder are complaining,”

Besides, in the past few years he’s found a new outlet for his energy: bicycling. “It seems to help rather than hurt my joints,” he says.

Bear in mind, we’re not talking about riding back and forth to the grocery store bicycling. The last two years he’s won his age division at the 206-mile Lotoja bike race from Logan to Jackson. He’s already put 12,000 miles on his road bike this year, and the year’s not over.

“I’m going to keep doing a lot of riding,” he says.

He also reports that he bought new skis this year and already has his season pass to Snowbasin. He plans to do a lot of skiing, too. And at the usual pace. Only maybe faster, without the camera.