MOUNTAIN GREEN, Morgan County — Buried in the mountain adjacent to I-84 in Weber Canyon, the Gateway Tunnel has been been a conduit for water to residents in Davis and Weber counties for nearly 66 years, with a flow rate sufficient to fill a football stadium with 25 feet of water every hour.

On Feb. 23, it was shut down for inspection and for workers to install a gate to provide greater flexibility in the system operated by Weber Basin Water Conservancy District, especially given construction risks posed by the massive expansion planned for U.S. 89.

The shutdown of the Gateway Tunnel happens only once every decade because idling it leaves residents dependent on deep wells for water supplies, a tricky and somewhat risky proposition for the fast-growing communities.

“For being over 60 years old, it is in great condition,” said Troy Stout, the district’s construction and maintenance manager during a walk through of the tunnel.

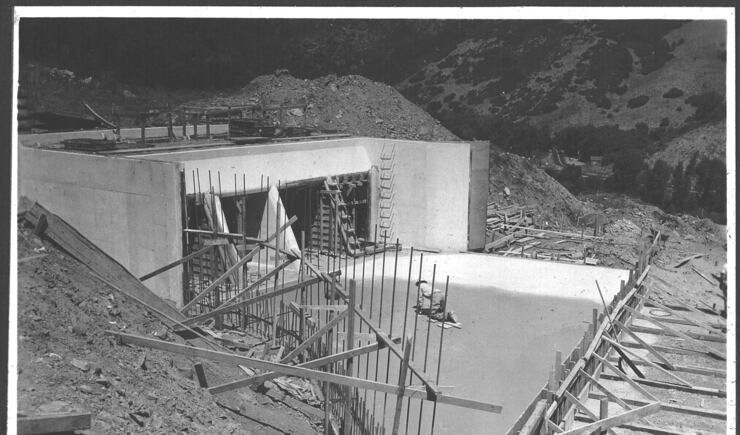

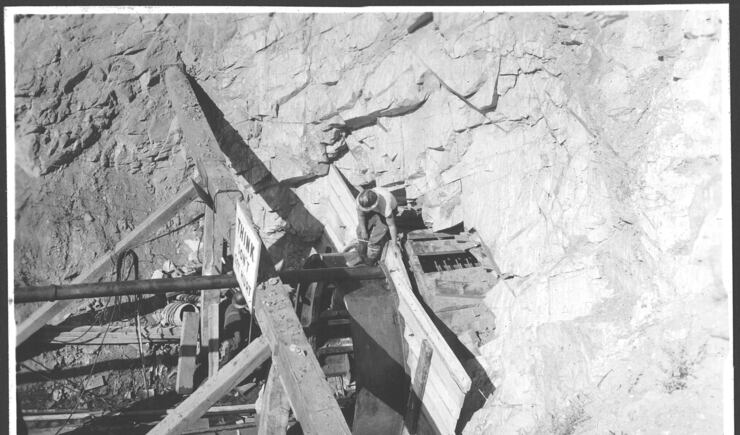

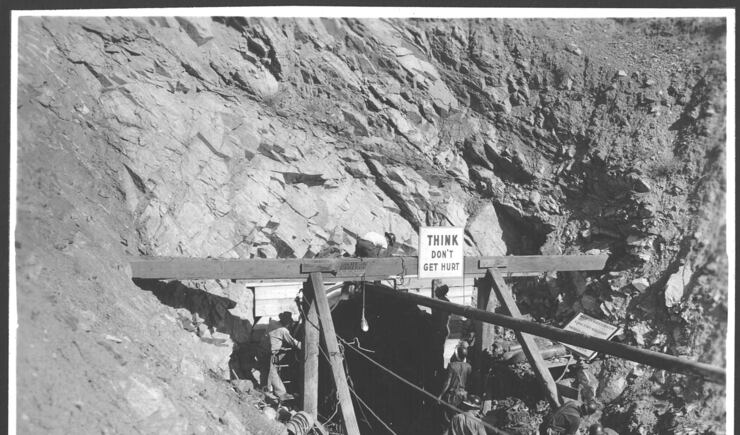

The tunnel is 9.4 feet in diameter, 3.3 miles long and was completed in 1954 by workers who started at each end to meet in the middle, much like the transcontinental railroad.

Concrete lining for the tunnel required 31,855 cubic yards of material with close to 45,000 barrels of concrete.

“It is impressive that back in the 1950s given how narrow this canyon is how smart it was to dig that tunnel,” said Darren Hess, assistant general manager for the district.

“It’s in excellent shape,” he added, pointing out how the constant flow of water through the tunnel hydrates the concrete and its extensive lining protects it from the freeze-and-thaw cycle that would render it vulnerable to cracks.

The tunnel is fed by the Weber River, which 8 miles upstream is diverted to the Gateway Canal. After it leaves the tunnel, it hits a bifurcation structure. Water either goes north to Weber County via a 48-inch pipe or south through Davis County in the Davis Aqueduct, which is 84 inches in diameter. All of it is gravity fed.

A couple of employees of the district live on government property below the tunnel to monitor the infrastructure 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

The nearly $2.5 million tunnel was completed in late 1954, a full year ahead of schedule by Utah Construction Co. employees who worked three shifts six days a week, blasting through an average of 51 feet of mountainside per day.

When they met up in the middle, Hess said the alignment was off by just 3 inches, which was handled easily due to the amount of fill material that was used.

Hess said the tunnel, discreetly tucked away in the mountain and out of sight, is the district’s workhorse for water supplies.

“This facility is critical to everything the district does,” he said.

Water suppliers in the ’50s could have chosen to install a pipeline down the narrow canyon, but instead opted for the tunnel, a decision which makes the infrastructure less vulnerable to landslides or earthquakes, Hess said.

“They could have taken the much easier route,” he said, adding that the engineering and ingenuity embraced at the time provides so much more certainty for the district’s customers.

On Monday, the tunnel received its rushing water to meet the needs of 700,000 people.