When it comes to Americans’ perceptions of what schools should teach about racial history and progress toward racial equality, results of the latest American Family Survey reflect a deeply polarized nation.

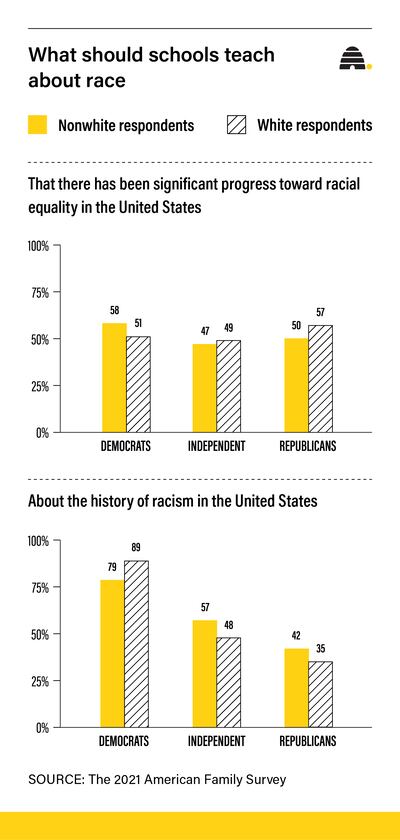

While majorities of Republicans and Democrats agree that schools should teach about racial progress, the results reveal deep divisions about teaching the history of racism.

Among Democrats, nearly 8 in 10 nonwhites and close to 9 in 10 whites agree that school curricula should teach the nation’s troubled racial history. Among Republicans, 4 in 10 nonwhites and more than a third of whites, 35%, share that view, according to the latest American Family Survey results. Results of the survey were released Tuesday in Washington, D.C., by the Deseret News and Brigham Young University’s Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy.

Now in its seventh year, the American Family Survey looks at how families live and perceive current events. This year’s YouGov survey of 3,000 adults was conducted June 25 to July 8, just before COVID’s delta variant became widespread and prior to the start of the school year. The survey has a margin of error of plus or minus 2 percentage points.

Survey results suggest Republicans want to tell a positive story of racial progress, while Democrats see a need to deal directly with the nation’s fraught racial history. The biggest partisan gap is between white Democrats and white Republicans.

Those divisions are evident in America’s public forums across the country as elected officials and educators grapple with the nationwide reckoning on race and policing following George Floyd’s murder at the hands of police.

Floyd, a Black man, died while in police custody in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020. Former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, who is white, was sentenced to 22 1/2 years in prison for Floyd’s murder. A bystander’s video viewed worldwide captured Floyd’s dying gasps as he was pinned under Chauvin’s knee for 9 1/2 minutes.

The events led to the biggest outcry against racial injustice in generations.

Many state legislatures and school boards responded by passing laws and rules that expressly prohibit the teaching of critical race theory in K-12 public school.

Critical race theory, according to the American Bar Association, recognizes “that race is not biologically real but is socially constructed and socially significant.”

The theory also acknowledges “that racism is a normal feature of society and is embedded within systems and institutions, like the legal system, that replicate racial inequality. This dismisses the idea that racist incidents are aberrations but instead are manifestations of structural and systemic racism,” according to the ABA.

Becky Pringle, president of the National Education Association, the nation’s largest teachers union, stresses the need for truth and honesty about America’s legacy of racism.

“We can teach about the horrors of slavery, internment and forced resettlement. We can have honest discussions about today’s injustices and the threats to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness that still exist for many. We can objectively present to students the good, bad and ugly of our past so that they can build a better, brighter future. Our students need to learn about the times when this country has lived up to its promise, and when it has not. Honesty. That’s what they need from us. Truth. That’s what they expect,” Pringle wrote in a recent op-ed in USA Today.

According to the Brookings Institution, eight states passed anti-critical race theory legislation: Idaho, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Iowa, New Hampshire, Arizona and South Carolina. Only Idaho’s law uses the words “critical race theory” explicitly.

State school boards in Florida, Georgia and Oklahoma introduced new guidelines barring critical race theory-related discussions or instruction. Local school boards in Georgia, North Carolina, Kentucky and Virginia also criticized critical race theory.

Some 20 other states have introduced or plan to introduce similar legislation, according to Brookings.

The Utah Legislature passed nonbinding resolutions that urged the Utah State Board of Education to clarify in administrative rule what can and cannot be taught in Utah schools. The resolutions expressed that some concepts of critical race theory “degrade important societal values and, if introduced in classrooms, would harm students’ learning in the public education system.”

Utah’s state school board passed an administrative rule but debate continues regarding its application, such as common definitions and a framework to guide equity, diversity and inclusion instruction.

The divisions

Recent comments to Utah’s State School Board bear out the divisions nationally that are reflected in the American Family Survey.

Juliet Reynolds, a Utah mother of four adult children, said she took a deep dive into learning about queer culture after one of her children came out to her. She also immersed herself in reading the history of Black people, Indigenous people and other people of color.

“I often became overwhelmed with emotion because I couldn’t believe that racial oppression had become so deeply embedded in our society. I couldn’t believe that at 40-plus years of age, this was my first time hearing of most of this stuff. It had been omitted from my history books when I was young. If we were taught these histories when we were young, perhaps we would not be in this room divided over difference,” Reynold told the state school board at a recent meeting.

Yet another speaker, Kelly Strebel, said students’ “constitutional rights are being destroyed daily” by what they are taught in school.

“Critical race theory, Black Lives Matter, Common Core, social emotional learning, The 1619 Project (by the New York Times), Second Step are subjects that fall under the term American Marxism. All of these should now be known as step three and burned and destroyed for the damage that they create and are causing in our schools,” said Strebel.

While the two adult speakers represented divergent points of view, the American Family Survey indicates younger Americans strongly support teaching the history of racism. Among people ages 18-29 surveyed, more than 70% strongly or somewhat agree the history should be taught.

Along race lines, 75% of Blacks surveyed agree or strongly agree that schools should teach about the history of racism, compared to just over 60% of Hispanics and just under 60% of whites.

Among respondents who are college graduates, roughly 7 in 10 support teaching the history of racism compared to just over half who have a high school education or less.

Across four census regions nationally — Northeast, Midwest, South and West — the highest percentage of agreement was in the West, with greatest disagreement in the South.

The survey also found that a majority of all demographic groups agree that schools should teach that there has been significant progress toward racial equality in the United States while there were lower levels of agreement to teaching about the history of racism.

Who’s correct?

Martell Teasley, dean of the University of Utah’s College of Social Work, said it shouldn’t be an either-or proposition because students need a broad understanding of the nation’s history regarding race, racism and progress.

“There should not be a binary position. We need to do all of that. Part of the whole notion of American exceptionalism, as you know, is overcoming these things,” Teasley said.

He continued, “We should look at our history. Racism as part of American history, as well as gender challenges. In telling that story, there is a glorious story of people advocating for change. That also needs to be told. There’s many lessons learned by studying that history that make us a better people and a much more civilized people. So we have to study the past, to really understand where we’re heading in the future.”

Teasley said a faculty member from Oklahoma, who has a doctorate degree, knew nothing about the Tulsa race massacre until recently. On May 31 to June 1, 1921, a white mob attacked residents, homes and businesses in Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood, which was predominantly Black.

Many Americans were unaware of the events until the 100th anniversary of the riots this year.

“The event remains one of the worst incidents of racial violence in U.S. history, and, for a period, remained one of the least-known: News reports were largely squelched, despite the fact that hundreds of people were killed and thousands left homeless,” according to history.com.

Not knowing one’s history can stir anger in some people, Teasley said. “So there’s a harm that’s being caused by not explaining history to people,” he said.

Teasley likened it to parents not telling one of their children that they have a different biological parent than others in his or her family. “Think of the harm that’s done by telling them that some time later in their life instead of being upfront about it when they’re a child when they can accept these things,” he said.

“We rob people of that when we don’t tell them their history, and therefore, we pull away from what makes us an exceptional country,” Teasley said.

Critical race theory

Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, has been an outspoken opponent of the teaching of critical race theory in public schools.

He and Sen. Rick Scott, R-Fla., have introduced legislation that, if passed, would ensure schools would not be required to teach critical race theory if they accept federal educational funding.

“Critical race theory undermines our founding principles, institutions, social mobility, and history itself — and schools should not be forced to teach it,” said Lee in a statement.

“This bill will ensure that with the receipt of federal funds, states and local educators will not have to.”

The bill would amend the Higher Education Act of 1965 and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 to clarify that nothing in those acts require the use, teaching, promotion or recommendation of any academic discipline, program or activity that holds anti-American or racist principles.

Earlier this year, in an opinion piece written for the Deseret News, Lee said critical race theory attacks what it means to be an American.

“Just what is at the heart of this ideology? Critical race theory is based on the premise that the United States is a fundamentally racist country and that American hallmarks such as the Constitution, property rights, color blindness and equal protection under the law are vestiges of white supremacy, patriarchy and capitalist oppression. It categorizes people as either oppressors or victims based on skin color, making race the prism through which American life is viewed,” he wrote.

“But this view gets it exactly wrong. The problem is not America’s principles; the problem is rejecting them.”

Kathleen Riebe, a Democratic state senator in Utah, is a public schoolteacher. She voted against a nonbinding resolution that urged the Utah State Board of Education to ban what Republican leaders described as “harmful” critical race theory concepts. In the Utah House of Representatives, Democrats walked out of the chamber in protest prior to the vote during an extraordinary session of the state’s Legislature.

Some of the partisan differences with respect to school teaching about race reflected in the American Family Survey results can be attributed to Democrats’ belief in “the big tent,” said Riebe.

“When you’re a big tent you believe that ‘I don’t have to live through what’s happened to other people to have compassion for that,’ whereas Republicans, they’re like, ‘Pull yourself up by your bootstraps,’” Reibe said. “When I don’t have bootstraps and I don’t have boots, it makes it a little hard, you know.”