After years of raising funds and support for others, Michael “The Rainmaker” Nebeker — a man who has generated more than $100 million for a variety of humanitarian causes over the past four decades — has reversed field.

Now, he’s doing it for himself.

His story is a case of one good thing leading to another. Mobile Surgery International — the nonprofit he started three years ago — is a direct result of the many years he spent watching U.S.-based medical nonprofits fly in doctors, nurses, anesthesiologists, medical equipment, et al., to developing countries, where they would set up shop in the wing of a local hospital and deliver as much help as possible before returning to America, usually after a week or two.

Why not bring in your own hospital — a movable one on wheels — and stay as long as needed to train the locals so they can carry on when you move on to the next area in need?

In a nutshell, that is Nebeker’s new charity.

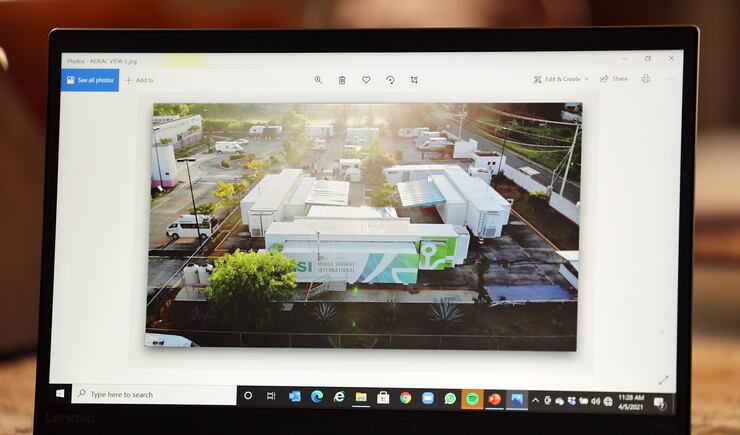

For now, he has just one mobile hospital in just one location: Oaxaca City, Mexico.

His big dream — and no one has ever accused Nebeker of not dreaming big — is to have movable hospitals circle the Earth, thereby saving the lives of the 17 million people worldwide who, according to The Lancet, die every year due to a lack of surgical care. That is more than all those who die from HIV, malaria and tuberculosis combined.

“Mobile hospitals are a game-changing model,” says Nebeker. Not only do they eliminate the hefty transportation and living costs from bringing in foreigners, but “care isn’t something you can just fly in and distribute, like money or shoes or water. To be efficient and effective it needs to be ongoing.”

Effort to help others stretches back decades

You have to travel back 47 years to find the source of Michael Nebeker’s humanitarian heart.

He was Elder Nebeker then. It was 1974 and he had freshly arrived in Thailand as a 19-year-old missionary for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He and his companion were traveling by train to their area when they stopped at a station and were approached by a young woman with a 6-month-old baby in her arms. She held out her hand, begging for money.

“Don’t give her anything,” advised Nebeker’s companion. “If you do that, everyone will see and we’ll be inundated by beggars.”

The missionaries watched as the woman walked a little ways away, went behind a bush, and snapped her baby’s arm in half.

With the screaming baby, she again approached the missionaries with her hand out.

“I get emotional whenever I tell this story,” says Nebeker. I remember thinking, “how desperate do you have to get?”

They wound up giving the woman money not just for food but to get to the hospital.

“That has lived with me the rest of my life,” says Nebeker. “That’s why I do what I do.”

After returning from his mission and graduating from the University of Utah, he was back in Thailand, working for the Pearl S. Buck Foundation, taking care of children orphaned by the Vietnam War. After a few years in the public relations world, he worked for the International School in Bangkok, spearheading a $33 million fundraising campaign that built a new school for the kids when they lost their lease on the old one.

That was followed by a return to Utah as development director for Waterford School in Sandy, where he led a successful capital campaign. Then, in 2002, he went to work as a fundraiser for Operation Smile, the Virginia-based charity that provides care around the world for children with cleft lip and cleft palate.

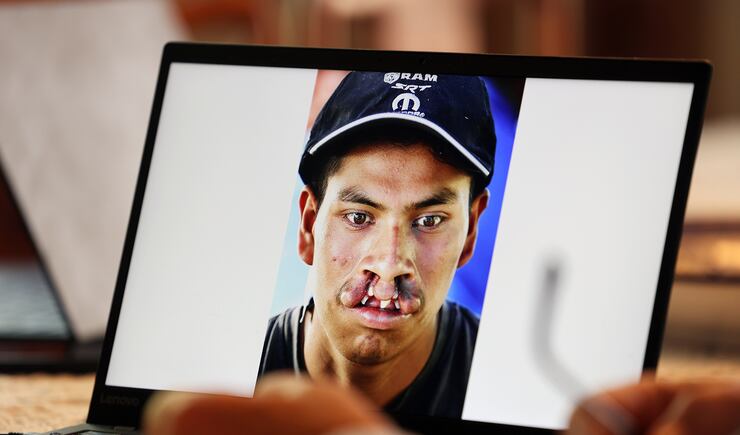

Seeing firsthand the horrors of cleft — the disfigurement and stymied speech development that render its innocent victims outcasts from society — had as profound of an effect on Nebeker as watching that mom in Thailand break her baby’s arm.

He helped raise millions for Operation Smile, highlighted by a direct response TV campaign starring Roma Downey that cemented his rainmaking legacy, He was hard at work raising even more when a series of circumstances beyond his control sent him on his own orbit with Mobile Surgery International.

The genesis was a lunch with Jerry Moyes, a Utah native and a big-hearted Operation Smiles board member who founded Knight-Swift Transportation, one of the nation’s largest trucking companies.

Moyes had recently attended a NASCAR event in Phoenix, where he watched the race from a hospitality suite that consisted of two trailers pulled together. The inside wall had been knocked out and windows added, resulting in a comfortable, roomy spot right next to the track.

If you could make a hospitality suite out of two trailers and put it wherever you wanted, Moyes mused, why not a hospital?

Building something ‘bigger than ourselves’

And if you could make a hospital that moved, why not take it to Mexico, plant it in one of the low-income environments Operation Smile served, and start doing surgery indefinitely, instead of flying in and out for just a week or two?

Nebeker loved the idea. He found a company in Massachusetts that made mobile hospitals, ordered a triple unit (thanks to Moyes’ generous donation), and transported it to the Mexican border ...

… and there ran into a snag.

The Mexican division of Operation Smile turned the mobile hospital down. They didn’t feel it fit their business model. They did not want the responsibility.

Left with a perfectly good hospital no one wanted, Nebeker decided to adopt it as his own.

With the blessings of Moyes and other donors, he incorporated Mobile Surgery International as a 501c3 nonprofit and made arrangements to transport the trailer/hospital to the Mexican state of Oaxaca, in the southern part of the country.

The hospital’s first use was to provide medical support in the wake of the magnitude 8.2 earthquake that rocked Mexico in September 2017. That was followed by COVID-19 assistance through most of 2020.

Finally, on Nov. 1 last fall, Nebeker’s hospital started doing what it came for: providing free of charge cleft lip and cleft palate surgeries, along with all necessary aftercare, including dental needs, speech therapy, psychological counseling and ear, nose and throat consultation.

The hospital’s surgeons have taken up full-time residency in Oaxaca; most of the rest of the staff is made up of locals.

The plan is to train local doctors so they can carry on the cleft-repair work at Oaxaca’s existing hospitals when Nebeker’s mobile unit pulls up roots and move on.

“I think we need to be here for two years,” says Nebeker, who travels frequently between Utah and Oaxaca. “Then we’ll go to (the neighboring state) Chiapas.”

Nebeker’s right hand in his venture is his 24-year-old daughter Lismore. A people person with the persuasive personality of her father, Lismore, who graduated with a degree in public policy from the University of Utah, has taken MSI’s cause to the United States Congress.

Her lobbying efforts with key Congress members succeeded in getting language in the charter of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) that specifically identifies “neglected surgical conditions” as a legitimate cause that is worthy of a slice of the $41 billion the agency annually distributes to low- and middle-income countries around the world.

Such an imprimatur from the U.S. government has the potential to open some big windows of giving for Mobile Surgery International.

“We’ve got the language (in both the USAID charter and the appropriations bill that funds it) and for 2022 we are asking for $100 million and I think we’ve got a really good path toward getting that,” says Nebeker.

The goal, he states, “is to create something so much bigger than ourselves. We’re the only ones doing it right now, literally, but it’s a system that can be replicated everywhere. We want these all over the world.”

That thought, that possibility, “consumes me,” says a 66-year-old man whose only plan for retirement is to never do it. “I need 30 more years. Then I can hand it over to Lismore.”