Utah's largest transit agency viewed its one-month trial of free fare service in February as "very successful," raising ridership 16% from the previous month.

It was, at the time, Utah Transit Authority's best ridership month since the COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted the agency's service in March 2020. UTA has since posted stronger months as its ridership has steadily returned to 75% of pre-pandemic levels.

There are other incentives that have also waived fares for some riders. For instance, UVX in Utah County has remained free because of federal funds the project received, while Salt Lake City leaders helped pay for transit passes for all Salt Lake City School District students and employees this school year.

"This issue is one that we have all focused on to a degree," said Andrew Gruber, executive director of the Wasatch Front Regional Council. "I will say that we have seen — it's measurable but it's still kind of piecemeal — that when fares are zero, when there is no fare, the ridership has had a notable increase."

But can permanently removing fares further increase ridership so that UTA serves as a viable alternative in decreasing traffic and traffic-related air quality woes along the Wasatch Front? And if so, is it worth the cost of removing fare collection?

Those are the questions that UTA, the Utah Department of Transportation, Wasatch Front Regional Council, Mountainland Association of Governments and a few other organizations, including the consulting firm Nelson/Nygaard, are seeking to figure out. However, their curiosity sparked a study that looks into the feasibility and incentives of removing fares from UTA service.

Though the study is not yet completed, the group presented its early findings of four potential options to members of the Utah Legislature's Transportation Interim Committee during a hearing Wednesday. The study, Gruber explained to the committee, won't recommend any decisions; rather, it's designed to provide information that lawmakers to use if they consider waiving fares in the future.

"We are not advocating one of these," he said. "Each one of these options represents a different way we can get more people to begin utilizing UTA services, improve mobility throughout the region and leverage the investments that we've already made."

How important are fares?

The study notes that UTA expects to collect about $34 million in fares this year, and $36 million next year. Both figures would be the highest since the pandemic. However, the agency collected an average of $52 million over the five years before pandemic-related ridership losses.

This year's fare collection projection only accounts for about a tenth of UTA's overall revenue. Fares did account for as much as one-fifth of all revenue in 2015; however, that number continues to shrink due to the rise of other revenue sources like sales tax, federal support or other options.

"Overall, fares provide a relatively small part of the operating dollars that UTA needs to operate on an ongoing basis," said Thomas Wittmann, a senior principal at Nelson/Nygaard.

Still, it's a big chunk that UTA would have to recoup from new sources, such as the Utah Legislature.

The report estimates the cost would be about $34.5 million to remove it altogether or $38.5 million for a one-year pilot program, using 2023 projections. These costs take into account the loss of fare, as well as the cost of running fare collection services and growing paratransit services.

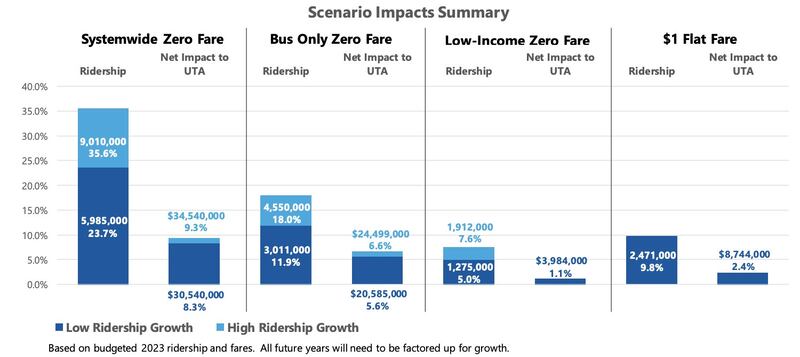

The report also looked at other alternatives, such as waiving fares just for buses. That would cost closer to $24.5 million. It would cost a tick under $4 million if fares are removed for anyone with an income that's 150% of the current federal poverty rate. Another option is to lower the current fare of $2.50 per ride to $1, which would cost about $8.8 million.

However, Wittmann said any of these changes would likely affect ridership, which could be helpful in terms of removing vehicles from roadways.

When reviewing similar policies in other places, like Kansas City, Missouri, or Richmond, Virginia, they've found that ridership increases, existing transit users ride more often and more people are willing to try transit for the first time, he said. That's because it removes a "barrier of entry," including the nerves first-time users may have when it comes to not knowing how to pay to ride a bus or train.

Removing fares altogether would result in 9 million additional riders, a nearly 36% increase, the organizations behind the study project. The other options have the potential to raise ridership from anywhere between 7.6% to 18%, according to the projections.

"The systemwide zero fare shows the highest potential ridership increases but also the potential costs associated with it," Gruber said.

Wittmann cautions that the study still isn't complete, though. The team is still reviewing other elements like quantifying community benefits associated with removing or reducing fares. The costs are also expected to increase with inflation beyond 2023.

Why UTA may take some time to sort it out

But Utah lawmakers aren't sure if they're willing to get on board with covering the revenue loss associated with removing fares.

The overarching theme seemed to be whether UTA should be a business or a community service. For instance, Rep. Karen Peterson, R-Clinton, likens UTA fares to UDOT's transition to more road usage fees.

"I'm having a hard time wrapping my brain around that actually, because I do believe that fee for service is a good tax policy — so that's a struggle for me," she said.

Others on the committee added that they aren't sure that the fare cost is the reason more people don't ride public transportation.

Rep. Candice Pierucci, R-Herriman, said she frequently hears from her constituents — and her students as an adjunct instructor at Utah Valley University — about service quality more than cost. Improved service could cut down on travel times, which may entice drivers to make the switch to transit.

"They not asking for free fare, they're asking for frequency, reliability and accessibility, and I don't see how reducing fare meets any of those needs," she said. "In fact, I would say it's cutting into the ability to have revenues to be able to pursue those options."

Gruber agrees there is still work to go before suggesting fare cuts as a possible program, adding that he's appreciative of the feedback from the committee and the research continues. Some of the suggestions brought up in the meeting are things that the team may review in the future.

Taking in feedback from both sides, Sen. Wayne Harper, R-Taylorsville, noted that Wednesday's meeting is why he believes it's important to study the topic before rushing to any decisions.

"This is a big issue that we're dealing with," he said. "This is a significant policy discussion. ... This is a good study. They will be back with recommendations and then we'll have to decide what in our purview, as elected officials, is best for the state of Utah."