Almost half of the world’s pregnancies are unplanned, and the contraceptive burden has historically fallen on the shoulders of women. Aside from condoms and vasectomies, there doesn’t seem to be many options for men.

But a study published Tuesday in Nature Communications challenges that narrative with a drug that temporarily immobilizes sperm in male mice, and may very well work for humans.

Unlike most forms of male birth control currently being studied, which would typically require months of treatment, this one is short-acting. Mice were infertile within 30 minutes of taking a single dose and fertile the next day.

The drug, which would eventually take the form of a pill, essentially “turns off” soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC), an enzyme that causes sperm to swim.

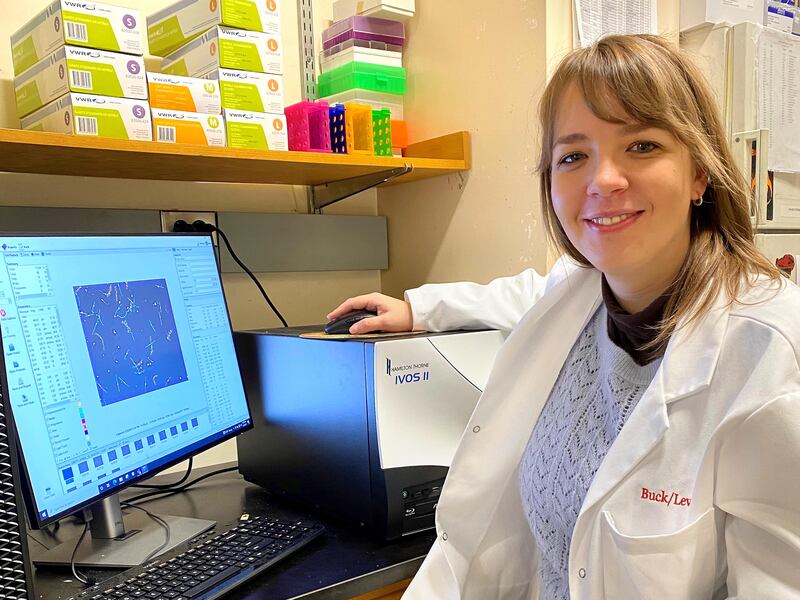

“We are inhibiting the protein that is kind of the ‘on switch’ in sperm — so the protein that regulates that onset of motility,” said Melanie Balbach, a Cornell associate who helped conduct the research.

Male mice received the inhibitor, then mated with females, impregnating none for 21⁄2 hours. Balbach said the mice didn’t experience any side effects, so testing the pill on humans is a strong possibility. Researchers are testing it on rabbits now, and should begin human trials in two to three years.

The lack of side effects is another factor that sets the study apart from other proposed male contraceptives, such as hormonal treatments.

“Hormones are really not something that is only important for reproduction — it also controls our mood, kidney function, everything,” Balbach said. “So if you kind of play with one part of that system and disturb it, then it’s kind of like a domino effect and you disturb it everywhere else as well.”

The search for a nonhormonal medication for men begs the question: Why is it accepted for women to endure the side effects of hormonal birth control? Balbach pointed to the fact that it’s easier for female contraceptives to get the Federal Drug Administration’s approval because the stakes are higher for women.

“So having a headache compared to dying because of a pregnancy — it’s a different risk compared to when a healthy male takes our pills,” she said. The differing risk factors may also be one of the reasons there’s been so little research on birth control for men.

“The bar for safety is much higher, which then kind of scares off pharma companies, because they really want to make profit at the end of the day, so they are just worried that they invest a lot of money and then it’s going to fail,” she said.

Budding research, however, suggests demand for male contraceptives may be higher than pharmaceutical companies think. In a study not yet published, Steve Kretschmer, executive director of the consulting firm Desire Line, and a team of researchers looked at how willing men would be to use birth control.

“When we dig into it, what we see is a desire to actually take on the burden, because they see how their female partners are suffering the consequences of taking the hormonal drugs,” Kretschmer said.

He said that was especially true in lower-income countries. In the U.S., 78% of men said they would use some form of male contraceptive at some point. That may be an overestimate of men who would actually use a contraceptive — the study also forecasts that about 70% of men wouldn’t use any contraceptives.

However, Kretschmer emphasized that the research was done before the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, making abortion no longer a constitutional right. He expects that the court decision might have changed people’s minds and looks to confirm that with more research in the coming months.

Balbach echoed that sentiment, saying funding for research of male contraceptives has increased since the national conversation about abortion surged.

Of all the proposed forms of birth control, men in the U.S. favored an on-demand pill, like the one Cornell has started to develop.

Both Kretschmer and Balbach say the shortage of research on birth control for men may also be due to social norms.

“Society kind of puts the burden of contraception, historically, on females,” Balbach said. “It was mainly men, at the time, that developed and were doctors, so they were just thinking, ‘We’ll just target the female,’ and that’s just what happened in the ’60s.”

The novel strategy would aim to help balance contraceptive responsibility between men and women and, according to the study, “revolutionize family planning.”