The future of Smith’s Ballpark remains a touchy subject a week after Salt Lake City revealed its vision for the stadium.

Although residents say there are elements they like about the Ballpark Next Community Design Plan, many said it also falls short of what they had in mind for the former home of the Salt Lake Bees in their first big opportunity to weigh in on it.

Many came to the Salt Lake City Community Reinvestment Agency’s meeting Tuesday afternoon to voice concerns with the amount of dedicated buildings compared to green space, building heights or even the possible placement of buildings at the site of the old stadium.

“I feel like the community’s comments were well unified in the items we’re requesting,” said Jeff Sandstrom, a neighborhood resident and member of the Ballpark Community Council, following the meeting.

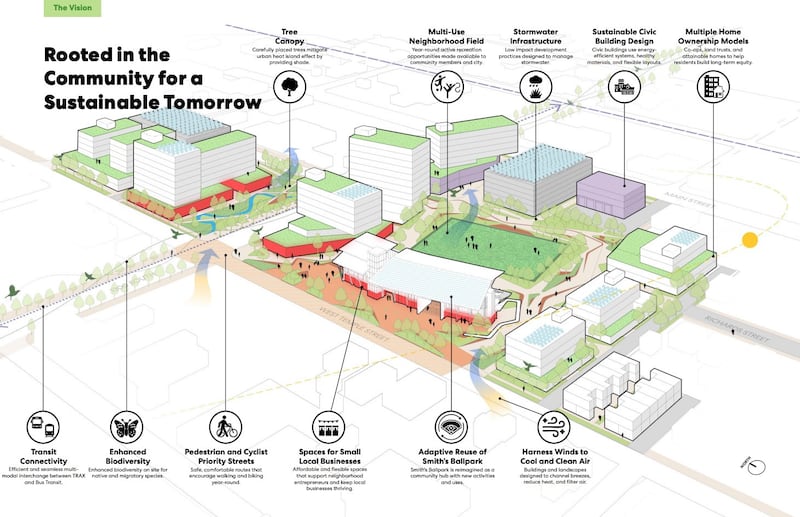

The draft design plan, released last week, calls for a partial demolition of the old ballpark, while about 3,700 of the ballpark’s bleacher seats — on the first-base side — and a piece of the old playing field would be preserved as a park and entertainment venue.

Various buildings would be scattered throughout other parts of the old stadium and northern parking lot, collectively bringing about 460 multifamily and senior housing units, along with a 125-room hotel, new retail space, a parking structure, a fire station and a library. Additional open space and new walkways would exist between the new properties.

The group behind the plan — the Reinvestment Agency and the design firm Perkins&Will — presented a draft of the final plan to the agency’s board members for the first time on Tuesday.

Marc Asnis, a senior associate at Perkins&Will, calls it an “evidence-based” document, which took into consideration neighborhood context, infrastructure, economics and the current state of the ballpark through feedback and data with residents and experts alike. A review of the stadium’s condition and project costs were also considered.

It was pieced together after planners and Salt Lake City Mayor Erin Mendenhall agreed that it would make more sense to partially adapt the stadium. How it would be torn apart is based on where the building’s expansion joints are located.

New buildings within the zone could be as tall as 120-200 feet along 1300 South, with heights lowering to 45-85 feet within other parts of the project area. This, project leaders say, aligns with recent changes to other parts of the neighborhood just outside of the project area, which caps buildings at 50-90 feet.

“When you look at this integrated into the future urban form of this neighborhood, yes, it’s going to be tall, but it’s going to be appropriately scaled with the adjacent parcels,” Asnis said.

Residents raised concerns about everything from the rigid building designs to building placements.

“This is one of the most beautiful stadiums, ballparks in the world, with its view of the Wasatch Front. How dare you place a parking structure in front of the people watching concerts?” said Cindy Cromer. “This is just horrid.”

Others brought up concerns about street safety along 1300 South, the relatively slim percentage of green space — after already having some of the fewest open space options in the city — and the loss of a community or recreation center in the design.

“I feel like the Ballpark Next plan has missed the community’s vision in some important areas,” Sandstrom said, explaining that the total number of housing units “feels like it’s overwhelming the entire project,” and reducing the impact of a community anchor like the park and venue space.

Leasing and homeownership issues were also raised about the housing projects. The city wants to “prioritize” homeownership and affordable housing opportunities, said Lauren Parisi, a senior project manager for the Reinvestment Agency, after the plan was unveiled. Getting there could require additional work from city leaders.

Salt Lake City Councilwoman Victoria Petro suggested that the agency explore community land trust and low-cost leasing options to ensure those provisions are included, following the concerns discussed during the meeting.

The project is expected to be carried out in four phases, starting with a search for developers for redevelopment along West Temple, as well as partial demolition of the stadium and a search for an operator of the entertainment venue. That is still expected to begin by the end of the year, Parisi said.

The timing of the project also drew concerns from residents on Tuesday. Some said they’re weary that it won’t be completed on time, pointing to the three years of construction in Sugar House — and other parts of the city with Funding Our Future road improvement bonds.

Those are provisions that could be addressed as planning shifts to construction within the next year or two. The final design plan could change, as could the product as it turns from concept to reality, added Salt Lake City Councilman Alejandro Puy, who also serves as chairman of the Reinvestment Agency board.

City planners took notes with the feedback received on Tuesday, and a community open house is planned at the ballpark beginning at 6:30 p.m. on Thursday. Sandstrom said he’s hopeful that the city will be receptive to the neighborhood’s concerns regarding the next steps for Smith’s Ballpark.

“I feel like they did listen and appreciated the comments we made,” he said. “I’m optimistic that they will take our comments to heart and try to incorporate them into the final plan.”