CEDAR CITY — Several weaknesses in cash reconciliation processes may have exposed several Iron County departments to theft, according to a new state audit.

The audit was released after a county employee was charged earlier this month with stealing more than $150,000 in cash meant for building permits.

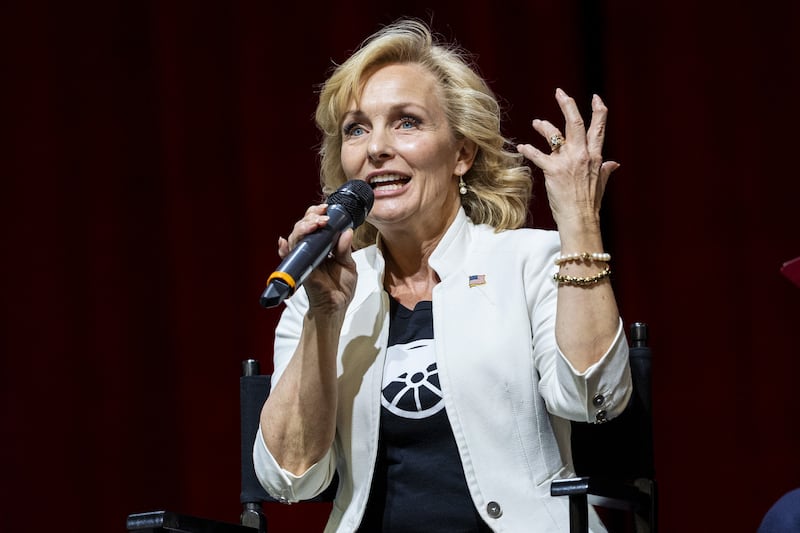

The office received a whistleblower complaint in April alleging that building permit fees had been misappropriated, State Auditor Tina Cannon told KSL.com Tuesday. That complaint prompted an audit and a criminal investigation, which resulted in an office manager for the county’s building department being charged with misusing public money and theft, both second-degree felonies.

“Investigators reviewed the documentation obtained from Iron County, and the combined total for missing cash payments for building permits between 2018-2025 was actually $164,671,” the charges state. “The Iron County auditor explained to (the state) that the building permits had been issued and marked that they had been paid for, but a significant number of cash payments for the building permits were never deposited into Iron County’s bank account and were not documented on end-of-month reports.”

A separate review of the county’s cash handling procedures was published by Cannon’s office on Tuesday. That review found that the county auditor did not properly validate deposit logs, and some departments lacked proper procedures for collecting and depositing cash payments. After looking into the situation, “it was immediately evident that a control weakness in the county’s reconciliation process had been exploited, resulting in the loss of funds without detection for years,” the report states.

“The best way that I’ve always explained it to people is dual control: to make sure that two sets of eyes (are) on every transaction and that there is a way to make sure that that check is in your system,” Cannon said. “Even ... Girl Scouts, Boy Scouts, every (Latter-day Saint) congregation has two sets of eyes on any cash that comes in or any payments that come in. It always goes through a two-step process.”

In the case of Iron County, Cannon said the county auditor did review a spreadsheet that matched the actual deposits that were made, but didn’t initially realize that the spreadsheet was created by the same employee who was depositing the cash and who was later charged.

“That’s not dual control,” she said. “If the same person is telling you how much money came in as is making the deposit, then you’ve got a breakdown.”

The review identified about $188,000 in missing funds from the county, dating back to 2018.

Cannon suspects that Iron County is far from the only municipality with similar weaknesses in cash reporting. And while she said she wasn’t trying to single out the county, she hopes it will be an example to other cities and counties to enact stronger controls before funds are stolen. Once the Iron County auditor realized the issue, she said the county acted quickly to make improvements to prevent it from falling victim again.

“We don’t necessarily want to use this as a way to embarrass Iron County, because we do think it’s a learning opportunity for every government entity out there who collects money,” the auditor said.

The report found that Iron County’s building department and county events center “are likely at higher risk for misappropriation due to the nature of the payments, lack of other corroborating records and the lack of a reliable boundary record.” Boundaries are the “point at which county personnel take custody of the payment,” according to the report, which recommends controls to track payments as they are received.

Auditors also recommended that county departments ensure funds are deposited into bank accounts within three business days of receipt. The report noted that the building department and sheriff’s office had been depositing funds once a week, which it said could risk funds being lost or stolen.

Iron County officials agreed with all three recommendations outlined in the audit and said they had implemented or were in the process of implementing all suggested changes.

“The county auditor’s office will be visiting each department in the county to review these findings, implement additional controls as needed, and verify that each employee that handles funds is aware of the controls put in place,” the county’s three commissioners wrote in response.

Cannon said the incident reiterates the importance of her office’s anonymous whistleblower hotline, which allows public employees and others to report potential wrongdoing or other issues for investigation.

“I guarantee you that no one has ever hired someone that they didn’t trust and that they have never lost money to someone that they didn’t trust, because they wouldn’t have put them in the position if they didn’t trust them in the first place,” she said. “This isn’t about whether or not you trust the individual; this is designing a system where they don’t have to just be trustworthy, that we are keeping good people good and honest people honest by the systems that we design.”

Correction: An earlier version incorrectly stated the audit was conducted after criminal charges were filed against an Iron County employee. The audit was released after charges were filed, but the audit and the criminal investigation both stemmed from the same whistleblower report.