On this episode of “Deseret Voices,” Dr. Lynn Bufka and host Jane Clayson Johnson talk about the American Psychological Association’s annual Stress in America survey.

The survey found that Americans are feeling divided and disconnected as we go about life in our little bubbles.

Bufka wants listeners to know that if they recognize those stressors in their lives, they are not alone. She offers ways to connect with others, even if it means skipping the self-checkout line for the one with the cashier at the grocery store.

Subscribe to “Deseret Voices” on YouTube, Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Note: Transcript edited by Steven Watkins

Jane Clayson Johnson: Dr. Bufka, it’s great to have you with us. Thanks for joining.

Lynn Bufka: Thank you for inviting me to be here.

JCJ: So you’ve been part of this Stress in America survey for many years now. It’s an annual report. Explain what this survey is and why it matters.

LB: Yeah, thank you. It’s a great question. We have been conducting an annual survey at the American Psychological Association since 2007. And we work with a polling firm that helps us identify a cross-section of the public.

So we ask questions about stress, about sources of stress, and we also expand our survey every year in different directions. We might ask people about their physical health and their stress. We might ask about how they’re doing as parents. We might ask about election-related concerns, the future of America. And this year, we really were asking about loneliness and connection and how does that relate to stress and overall well-being.

JCJ: And what’s the headline of the report this year?

LB: One of the things that we took away from it is just the number of people who were reporting some degree of uncertainty, some degree of loneliness, some degree of disconnection from those around them.

JCJ: One of the most striking findings I thought from the report was the societal division that many Americans are feeling. It is now a major source of stress for most Americans. Tell us what your data shows about that.

LB: There are couple things we asked people just do you experience a societal division or not sort of on a scale from not at all to often frequently. A significant portion of the respondents do and of those who are experiencing more societal division they’re also experiencing more disconnection and loneliness in their lives. So that really has an impact on the overall well-being of populations.

JCJ: Six in 10 adults feel this way. They feel there is some sort of societal division that’s causing major stress in their lives.

LB: Yes. And I think it’s one of the challenges that we face because we can create bubbles for ourselves. We can create bubbles for ourselves faster now than we ever could because I can decide I don’t want to like somebody on social media. I don’t have to pay attention to what they’re saying. It’s why gathering at the holidays can feel particularly stressful, because suddenly I can’t edit out the family members who I disagree with. So we don’t necessarily, we aren’t necessarily developing the skills for dealing with difference. And then that becomes scarier and it amplifies the division.

JCJ: Amplifies the division and also the entrenchment, right? We all get in our silos.

LB: Indeed.

JCJ: And I presume this cuts across the political spectrum.

LB: it does cut across the political spectrum. Interestingly, we found it really sort of across respondents. So there certainly are going to be differences in different subgroups among that, but it was more striking to us as we were looking at our data about just how respondents overall are reporting this.

JCJ: Americans aren’t just feeling divided based on what you found in your survey. They’re feeling disconnected. What does that distinction help us understand?

LB: Divided might mean I don’t agree with your points of view on various things. I see the world from one political lens, others see it from another political lens. But we’re also having a great deal of difficulty transcending those differences and feeling more disconnected. So there’s both the division, which can be distressing in and of itself to see communities really fighting it out over local issues, the nation fighting it out over big issues.

But then if we have a hard time seeing that the person who has a different point of view from us or the community that has a different point of view from us might still share some of the same values that we have, we’re gonna feel more disconnected as well. And it’s going to be harder to reach across perceived divisions to foster those connections.

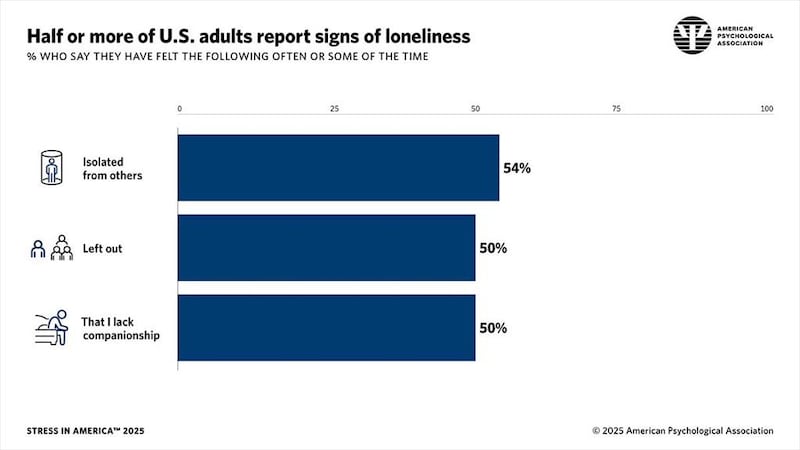

JCJ: In your research, Dr. Bufka, roughly half of adults in the United States report feeling isolated, left out, or lacking companionship. Why do you think loneliness is so widespread right now?

LB: Yeah, I mean, there’s probably many things that contribute to the experience of loneliness. Part of it is, how much do we actually just interact with other people? We’re in a world that’s increasingly telework or hybrid work, so you’re not interacting on a day-to-day basis with other people if you are in those work settings. There’s also the experience of: Do you have reasons to leave your house?

I have a dog, so I’m out and I meet my neighbors and my dog has an incredible social life and so that helps me stay connected to people. But we need to have reasons to get out and if we can do so much of our lives via technology and staying in within our living space, we have fewer reasons then to connect to other people. We don’t know the person who drives the bus who gets us to the metro station or we don’t know the person who’s sitting at the bus stop with us because we aren’t having that experience. They may not be our friends, we may not know them by name, but we don’t even have that moment of connection if we’re not in the world engaging with other people. So there’s sort of that basic level of just connecting with other people as we go about our daily business that we increasingly have less of because technology has enabled us to not have to do those things. And if we don’t seek those opportunities, we will have fewer opportunities for just general day-to-day connection. So that’s one contributor.

JCJ: We live in the most technologically connected age in history and yet rates of loneliness have doubled since the 1980s. What’s the difference between communication and connection and are we confusing the two?

LB: Being connected to people is part of that means being really feeling understood by others, feeling that you share some things in common. It’s not just a transaction of: I purchased online my groceries and I communicated with the person who helped me solve that problem. Or when we go to the grocery store and we go to a checkout, we may chat with the person who’s ringing up our groceries and both complain about the weather or realize that it’s somebody we went to high school with or that our kids go to school together. So you make a little bit of a personal connection in those face-to-face interactions that you’re less likely to do in a technology interaction. And when we have that personal connection — even if we might be divided on other issues — if we have a personal connection, that’s a connection that you don’t replicate in technology.

JCJ: I’m curious how does societal division translate into something so personal like loneliness?

LB: I think for many people feeling my point of view in my perspective on what’s good in society is not understood by a substantial portion of others. I may feel reluctant to disclose my points of view. I may feel reluctant to engage in conversation because, what if it’s going to be a really nasty encounter? Certainly the political models we’re seeing is that it’s not OK to disagree with one another. We don’t necessarily have models of individuals saying, “I really support X, I really support Y, we’re going to come together for a different kind of outcome.” We don’t see models of that. And it’s easy to think then that our fellow person next to us is going to follow a very confrontational model of exchange versus I’d like to get to know your point of view. So that can certainly put us off from even wanting to try to connect. It can raise our level of suspicion or discomfort around people that we don’t know. And that can just reduce our motivation to want to try to reach out to another person.

JCJ: And we feel so dug in, we feel so right about whatever our position might be, right? Which makes it even more difficult to find these areas of connection.

LB: That’s absolutely true. And I think one of the things that will be important for us to do is to try to understand other points of view. How did you come to that conclusion? And also try to find underneath the areas in which we both agree. We both may really want good education for our children. We just may differ about what might lead to that. But if we can identify the parts that we agree on, we might be more able to find a solution that gets us to the thing that we hold in shared value.

JCJ: Is loneliness something that people accurately self-identify or do many live with it without acknowledging it or even really having the language to describe it?

LB: That’s a great question. As a psychologist, I know that many people don’t have a lot of language for their emotional experience and may not be able to say, “It’s loneliness I’m experiencing,” or “sadness” or “I’m anxious,” just “I feel bad and I’m not really sure what it is.” And one of the things about loneliness that for many people is surprising, you can be alone and not be lonely. You can be with other people and feel lonely. So loneliness and aloneness are two different things and we don’t always discriminate that very well.

JCJ: And so what do you about that? What if you’re in a group of people and you feel completely alone?

LB: Well, look at the group of people. Are you in the right group of people? Perhaps you’re not in a group of people that you find shared values, that you feel comfortable being present in for whatever reason. Maybe it is a group that you could feel comfortable with, but you have to push yourself a little bit to reach out and make that connection. So I’d start with being in the group and trying maybe one-on-one to make a connection.

You know, I had the experience years ago where I was in a group, we were divided into pairs and we were told that we were matched with somebody because we had something in common. We learned afterwards that we were just randomly paired, but every pair found a connection. And that has stuck with me, that I likely have a reason to be connected to everybody around me. I just don’t know what that random connection is. And I just think that that lesson is so valuable that I will have something in common with everybody. I may not immediately recognize what it is, but if I explore, I will find something in common.

JCJ: You know, I remember interviewing the former U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek Murthy, a few years ago, and he cited research that shows that chronic loneliness can be as damaging to health as smoking or obesity. Your report shows strong links between loneliness and stress and declining physical health. Tell us what stood out to you most about those numbers.

LB: Yeah, I think that’s a really important point. It is really important for people to understand that. I think, a couple of pieces about that. Loneliness is something that we do have some capacity to change, but when we don’t change, it puts us at risk for other kinds of health conditions that as those accumulate, it becomes harder and harder to reverse. So absolutely, loneliness does put us at risk. Do we understand exactly why loneliness may put us at greater risk for physical health conditions? No, not necessarily, but it does underscore that humans were built for connection. And when we don’t have that connection, it does play with our overall well-being and our physical self.

JCJ: Who is most at risk, Dr. Bufka, for loneliness right now? And are there groups that might surprise us?

LB: Yeah, historically, we often think about older adults being lonely, but we’re finding that in our survey, even adults in the 18-to-34-year-old category are reporting loneliness. And that’s a really interesting question. Why is that? What might they be doing sort of developmentally at that stage in life? You know, for many, they might be transitioning out of their family of origin, going off to college or starting first jobs or leaving a college environment and starting a job. So it’s a time when you might have to put effort into being connected. You’re appropriately trying to make new independent connections outside of the family of origin, but that may be hard. It may feel difficult to do. And if somebody is entering a work world where it’s a lot of virtual or hybrid work, you don’t have the ready-made connection points of everybody meets in the cafeteria for lunch or goes to the coffee maker where you can have the conversation with somebody. So there are perhaps less ways of finding that connection as well. So then you have to be more creative to create opportunities to feel that you’re with others and less lonely.

And I don’t want to put the burden all on the individual either. I think we need to think about this as a societal challenge of how do we foster connections, identify those who may be feeling lonely, and help them find ways to connect with others around them to ease that loneliness.

JCJ: And so bottom line from a psychological perspective, connection is absolutely essential to human health.

LB: Absolutely.

JCJ: So this report also reflects a collective anxiety about the future of our country. Three quarters of adults say that they’re more stressed about the country’s future than they used to be. Can you talk about those numbers and what’s driving that?

LB: Yeah, it’s an interesting question. Individuals from both major political parties are reporting concern for the future. And it may stem to seeing that societal division. Well, we’ve had in the past, challenges that we’re facing, we’ve often rallied together to address those. So if you think about what happened in after 9/11, and it was clear there was a challenge here as a country, individuals rallied and donated blood and supported first responders and looked after victims and their families, and there was really a clear coming together regardless of our perspective on various things. But that doesn’t last forever.

An external threat like that isn’t sufficient for us to overcome some of these differences that divide us and we’re finding it harder as a society to step over the differences to find the things that bring us together and to build on that, which then leads people to feeling more concerned of can we do that. Are we going to be able to find the ways that we can move forward together towards a future that we all agree on, particularly when we tend to paint the vision for the future as being in high contrast? I’m going to leave out politicos and elected members of the government and appointees, but thinking about myself, my cousins, my neighbors, my colleagues who might live in other parts of the country. Underneath all that, we want safety, we want health, we want opportunities to pursue our interests and to support our families.

We don’t always agree on how to get there and the discourse gets so heavily focused on how to get there and the differences in the values about that, that we forget that underneath it, neighbor to neighbor, we’re just hoping to pay the mortgage, pay the rent, keep the lights on, feed the kids, maybe enjoy a quiet evening with somebody we love watching a movie. Those are universal kinds of things we’d like to be able to do, but when we find it hard to talk across difference, it makes it hard to see a future in which those things are likely.

JCJ: So how do you see these numbers? I mean, this feels like it’s a new era in America.

LB: It concerns me and as a citizen in this country, I think about that and think about how do I make connection? What am I doing? What are the things that I can do that keeps me connected in my local community with my neighbors, with the people across the street who I only know enough to wave to them as they go in and out. But are there things that I can do to foster connection? I think about that as a citizen, as just a person who lives here and of course as a professional. How do you grow those relationships, help people feel like they belong, that they’re welcome despite whatever they bring in the door, but that they as a person are welcome, wanted, and wanted to be understood and included. This is really a concern that everyone can take a part in and try to do something about.

JCJ: In the survey, when you asked what Americans feel about their country today, people chose an interesting mix of words. They said, “freedom,” “hope,” “corruption,” “division,” and “fear.” That was an interesting collection of words. How do you interpret our collective mindset?

LB: What’s happening in our country is not something I’ve seen before. I don’t know where it’s going to lead. Uncertainty is something that definitely makes us feel anxious and fearful. However, hope is something we need desperately in order to try to overcome differences and to create change. And I think our respondents and the broader society are trying to hold on to that because we all know that hope does make a difference for us to see things in a new light, to be willing to try something different, to reach out a hand across a backyard fence, across an aisle, anywhere that it’s possible to build those relationships. So that hope part needs to be there as well.

JCJ: What does give you hope when you look at the numbers, when you look at the data from this report, because there are signs of resilience in it?

LB: Mm-hmm. You know, people talked about finding purpose in their relationships with their families, with their close friends. And we know that purpose, community involvement and shared experiences all buffer stress and counter loneliness. So people are telling us that and they’re telling us that things like checking in or volunteering or sharing a meal makes a difference and that’s exactly true.

It can be hard to try to reach out and make connections and feel like it’s not accepted. Figure out how to overcome any reluctance there and be willing to put ourselves out to be maybe a little more vulnerable, to risk what could happen next. What could happen next might surprise us. It might surprise us in a way that doesn’t feel so good or it might be amazing and you might discover, “Wow, this person I’d seen off and on crossing the same jogging path,” whatever, “there’s a connection here that I never expected.” So if we don’t take the risk, we’ll never know. And I’m hopeful that people will, as they think about this, realize there’s benefit to taking the risk to finding out what could happen.

JCJ: People also told you that they may be reevaluating what gives their lives meaning in this period of societal division, but they haven’t given up on finding purpose as they move forward.

LB: We know that there’s several things that can give us meaning in our lives. And certainly having a sense of purpose. And that sense of purpose could be derived from our work. It could be derived from volunteering somewhere. It could be derived from giving back to our community in different ways. It can also be derived from creating. Whether it’s crafting or deeds of kindness or simply appreciating love, goodness, truth, beauty, the interactions of little children with one another, and pausing to appreciate that and seeing the beauty in that can help people feel inspired to find purpose. Another area that people can feel some purpose in is taking a courageous stance towards life’s difficulties, seeing that something is challenging and deciding that I’ll do something about it and that could be something in one’s own personal life or in the larger world, but that can give a person a sense of purpose as well. And that sense of purpose really is so beneficial for humans. We need that in our day-to-day lives. The sense of purpose may change over time, but the need for a sense of purpose does not change.

JCJ: So for someone listening right now who feels lonely or overwhelmed or disconnected, what is one small step they can take today? One meaningful connection that they can make.

LB: First of all, I’d say, “I’m sorry you’re feeling that way and you’re not alone.” It may be recognizing that a lot of people around you also feel disconnected and alone, may help you feel a little more willing to do that one small step. Because maybe it’s not just about you needing to feel connection, but it’s your neighbor also needing to feel connection. So I would encourage people to think about what is in their lives currently. Do they live in a place where they have neighbors nearby that it’s possible to begin to say hello to and initiate a conversation? Is it possible to think about volunteering somewhere? Is it possible to, instead of always choosing the self-checkout line, go through the line with the cashier and spend time chatting with that person to begin to engage differently with the world around you. It may not always feel good every single time, but that doesn’t mean you don’t do it again.

And I think that’s another important idea for us to all remember is that it doesn’t have to be perfect every single time, but to give ourselves credit for when we do make that effort that we tried something that perhaps we thought was a little impossible and we tried it and it was OK. Maybe it wasn’t perfect or maybe it was amazing and now we feel motivated to do it again. But the fact that we tried doing something different, how did that make us feel? Did it make us feel any better? Any worse? About the same? Well if it was about the same or better, why not try it again? Because it’s more likely to make a change than having done nothing different.

JCJ: So leave us with one message that you hope listeners take away from this report. With some numbers that are in some ways discouraging, what do you want us to know?

LB: Human beings are resilient. We are resilient people. We can address challenges and do things differently, but we need to do that. We are better at that when we connect with others around us. It may feel scary and hard to initiate connection, but the rewards are great when we’re able to do that. And finding the ways that allow you to move beyond what you’re currently feeling comfortable with are likely to lead to significant positive ways of viewing the world around you.

JCJ: Dr. Lynn Bufka, thanks so much for being with us today, for the information and for the prescriptions for us. We appreciate it.

LB: Thank you.