On Feb. 27, 1860, Abraham Lincoln gave his famous Cooper Union address in New York City. The speech catapulted Lincoln from a largely unknown Republican candidate for president to a real contender for the party's nomination.

Lincoln had been born in Kentucky in 1809 and his family had soon moved to Indiana before settling in Illinois, at that time part of the American frontier. Lincoln worked a variety of jobs before studying law and working as a lawyer. In 1846 he ran for Congress as a Whig, where he opposed the Mexican-American War under President James K. Polk. After serving only one term, Lincoln returned to his law practice in Illinois.

Lincoln had been a passionate opponent of slavery, though he was also a realist. He opposed the war with Mexico largely because he knew it could result in the expansion of slavery to the new western territories, and empower the slave power in the south. For Lincoln, the hypocrisy and twisted, self-serving morality of the Southern slave power was self evident, and he believed that Southern intransigence would eventually lead to war unless steps were quickly taken.

When the Whig party disintegrated in the early 1850s over the slavery issue (and by extension the events in Bleeding Kansas), the Republican party was formed. Where the Whig party had included many Southerners, however, the Republican party was firmly anti-slavery and predominately Northern in composition. The new party was not an abolitionist party, however. Though its members wanted to end slavery, they knew that the South would never accept immediate and total manumission of their slaves. Rather, Lincoln and other party members held that the Federal government should not touch slavery where it already existed in the Southern states, but it must prevent the extension of slavery to the west.

In 1858, Lincoln ran for the United States Senate seat held by Illinois' Stephen Douglas, a Democrat. The two men engaged in a series of debates in which they considered the slavery issue, states' rights, and the question of Southern secession. Ultimately, Lincoln lost the election, but the arguments he put forth in the debates brought him a measure of national attention. For the first time in his life, Lincoln was now a national figure and a viable possibility for the White House.

Lincoln, however, faced stiff opposition within the party. The frontrunner was William Seward, the New York senator whose passionate anti-slavery was well known. Many considered Seward the obvious choice for the Republicans in 1860s. Others, however, believed him to be too uncompromising and rigid to represent the party and deal with an already hostile South. Several other figures also appeared to have a shot at the nomination: Edward Bates of Missouri, Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, and the party's first presidential nominee, John C. Frémont, who had lost to Democrat James Buchanan in 1856.

There were others as well, and Lincoln knew he had to really make a name for himself if he wanted the nomination. For his first step, he began to prepare and circulate his arguments from the debates with Douglas. Next, he began to accept invitations to speak on these national issues from prominent circles. One such invitation came from Congregationalist minister Henry Ward Beecher (brother of author Harriet Beecher Stowe), who asked Lincoln to speak at his Plymouth Church in Brooklyn.

Lincoln realized the importance of making a good impression with this speech. Not only was it at the behest of one of America's most prominent preachers, not only was it in the east, far away from his mid-west power base, but it was also in Seward's backyard. Lincoln benefited from the fact that many prominent Republicans publicly wished him well, largely hoping for anyone to emerge to challenge Seward. This anti-Seward clique within the party included prominent newspaperman Horace Greeley and anti-slavery advocate (and future Lincoln ally) Frank Blair. It is a mark of Lincoln's understanding of the importance of this speech that he spent $100, a considerable sum in the mid-19th century, to buy a new black suit for the occasion.

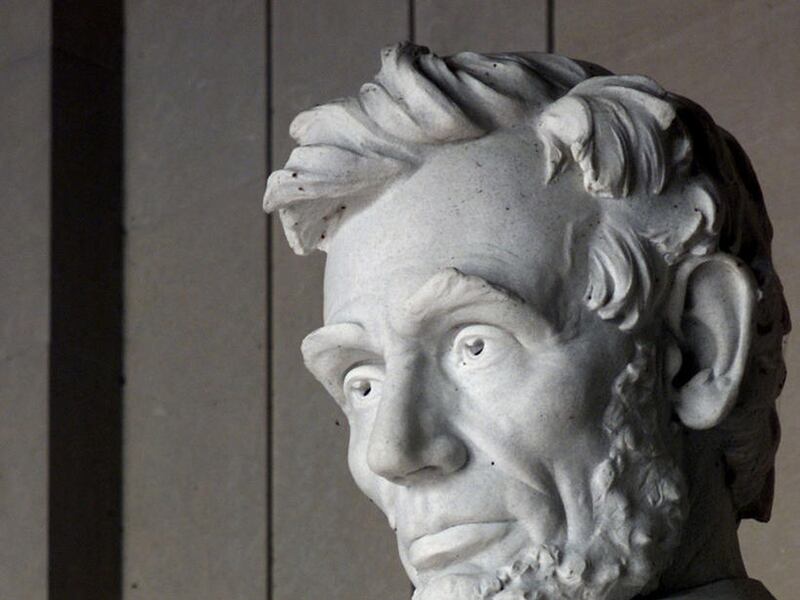

The anti-Seward clique soon went by the name “Young Men's Central Republican Union,” despite the advanced ages of many of its members. This body then assumed the sponsorship of Lincoln's appearance, heavily publicized it, and moved the speech to Manhattan’s Cooper Union, a private college established only the year before. With the speech scheduled for the evening of Feb. 27, Lincoln had the day to himself, and took the opportunity to visit the photography shop of Mathew Brady and have his portrait taken.

When the time came for the speech, the audience didn't quite know what to expect. After all, Lincoln was a man from the frontier. In the book “A. Lincoln: A Biography,” biographer Ronald C. White Jr. included a description of Lincoln from Charles C. Nott, a lawyer and speech organizer:

“The first impression of the man from the West did nothing to contradict the expectation of something weird, rough and uncultivated. The long, ungainly figure, upon which hung clothes that, while new for the trip, were evidently the work of an unskillful tailor; the large feet; the clumsy hands, of which, at the outset at least, the orator seemed to be unduly conscious; the long, gaunt head capped by a shock of hair that seemed not to have been thoroughly brushed out made a picture which did not fit in with New York's conception of a finished statesman.”

Lincoln quickly attacked Douglas' arguments that the founding fathers held that the Constitution forbade the federal government from interfering with slavery in the territories. He noted that many of the “thirty-nine” men who had signed the Constitution had been in favor of outlawing slavery in the Northwest Territory Ordinance, which pre-dated the Constitution by a few years. In Lincoln's eyes, the fact that so many men, including George Washington, had supported the federal government's move to prevent slavery in the territories proved that the same men must have believed that the Constitution gave the federal government that power as well.

After examining the voting records of the “thirty-nine” on issues of slavery, Lincoln stated: “But enough! Let all who believe that 'our fathers, who framed the government under which we live, understood this question just as well, and even better, than we do now,' speak as they spoke, and act as they acted upon it. This is all Republicans ask — all Republicans desire — in relation to slavery. As those fathers marked it, so let it be again marked, as an evil not to be extended, but to be tolerated and protected only because of and so far as its actual presence among us makes that toleration and protection a necessity. Let all the guarantees those fathers gave it, be, not grudgingly, but fully and fairly, maintained. For this Republicans contend, and with this, so far as I know or believe, they will be content.”

Lincoln then addressed those from the South. He challenged their notion that the Republicans were trying to play one section of the country off against the other: “You say we are sectional. We deny it. That makes an issue; and the burden of proof is upon you.”

He addressed the Southern accusation that the Republicans were exacerbating the slavery issue: “Again, you say we have made the slavery question more prominent than it formerly was. We deny it. We admit that it is more prominent, but we deny that we made it so.”

He also attacked the Southern slander that John Brown was acting in the interest of Republicans: “You charge that we stir up insurrections among your slaves. We deny it; and what is your proof? Harper's Ferry! John Brown!! John Brown was no Republican; and you have failed to implicate a single Republican in his Harper's Ferry enterprise.”

Lincoln wraps up his speech by asserting the Republican policy toward slavery: “Wrong as we think slavery is, we can yet afford to let it alone where it is, because that much is due to the necessity arising from its actual presence in the nation; but can we, while our votes will prevent it, allow it to spread into the National Territories, and to overrun us here in these Free States? If our sense of duty forbids this, then let us stand by our duty, fearlessly and effectively.”

Lincoln's final words were both a humble assertion of his belief in victory and a bold challenge to the South: “Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.”

In the book “Lincoln,” biographer David Herbert Donald wrote: “As a speech it was a superb performance. The audience frequently applauded during the delivery of the address, and when Lincoln closed, the crowd cheered and stood, waving handkerchiefs and hats.”

Lincoln's speech likewise met with critical acclaim as New York newspapers heaped praise upon the presidential hopeful. After his Cooper Union address, there was no doubt that Lincoln was a force to be reckoned with within the Republican Party. The address was perhaps the most important address that launched an American political career until Ronald Reagan's 1964 “A Time For Choosing” speech before a national audience on television.

Lincoln won the Republican nomination a few months later in May 1860, and went on to win the presidency in the general election that November. Lincoln's election later prompted 11 Southern states to secede from the Union, beginning the U.S. Civil War.

Cody K. Carlson holds a master's in history from the University of Utah and has taught at SLCC. He is currently a salesman at Doug Smith Subaru in American Fork. Email: ckcarlson76@gmail.com