Editor's note: This is first of three articles looking at the lives and careers of the Osmond family.

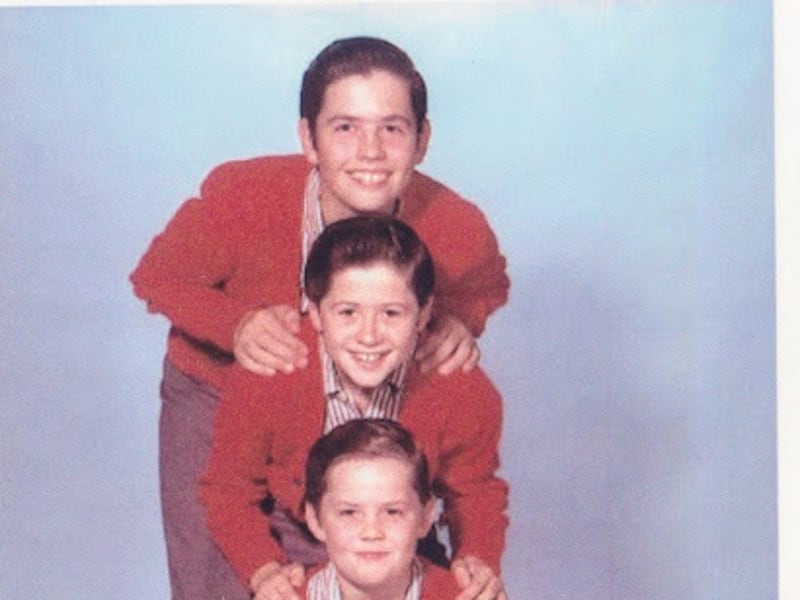

PROVO — They’re in their 60s now, every one of them, if you can believe it — Alan, Wayne, Merrill and Jay. Utah’s Beatles, as it were, the original Osmond Brothers from Ogden.

More Osmonds would follow in their wake, of course. Next came Donny, then Marie, then Jimmy, siblings they’d first share the spotlight with and then get out of the way. But in the beginning it was the four brothers, breaking trail with four-part harmony.

Without them, as their sister Marie says emphatically, “Nothing else happens. Nothing. We owe them everything.”

• • •

The church meetinghouse where it all started is still standing on 200 South in north Ogden, around the corner from the small farm at 228 N. Washington Blvd. that is not still standing — the place where George and Olive Osmond raised their family.

George was a counselor in the bishopric of the Ogden 29th Ward of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. One morning during bishop’s meeting, he volunteered his boys to sing in sacrament meeting. Alan was 8, Wayne 6, Merrill, 4 and Jay, 2. Their mom, proud but nervous, sat in the congregation, pregnant with Donny.

The boys sang “Oh Dear Lord in Heaven,” from the Primary songbook.

Read part two: Astounding Vegas run proves Donny and Marie still have it — together

Not even the most clairvoyant among those listening could have guessed what that song would launch: sales of 100 million records, 59 of them platinum and gold; worldwide fame and a family enterprise that 25 years later would be worth an estimated $100 million, all of which the Osmonds would lose because of the noble but mistaken belief that everyone was as honest as they were.

There was really nothing to portend such a future. George sang in a choir. Olive played saxophone in a band. They were musical but neither had any experience in the music business. She was from a little town in southeast Idaho. He was from Star Valley in western Wyoming. They met in the middle in Ogden in 1943 during World War II at the U.S. Army depot where she was a civilian secretary and he was a sergeant back from building airplane runways in England.

They married the next year. Olive was 19. George was 27.

After that, the kids came as if on a conveyor belt — nine children, eight of them boys, over the next 18 years, spaced almost exactly two years apart except for the last one, Jimmy, who arrived four years after his sister Marie.

The first two sons, Virl and Tom, were born deaf. Hardly a harbinger of what was in store for the Osmonds.

But it was precisely that hearing impairment that got George and Olive Osmond, after so many compliments about how good those boys sounded singing in church, to thinking: What if those boys were good enough to help pay for hearing aids for Virl and Tom?

Soon enough, George, in addition to working at the post office, selling insurance, driving a taxi and running his small farm, was scheduling playing dates for his singing sons; while at home Olive worked with them on their harmony. Alan sang bass, Wayne baritone, Merrill tenor and Jay lead.

The Osmond Brothers sang for family and church groups and parties in and around Ogden, passing the hat. In Salt Lake City, they got their first gig with an upfront fee ($200) at Wheeler Machinery. After they performed on KSL-TV’s “Talent Showcase,” host Eugene Jelesnik sent a film to bandleader Lawrence Welk. After receiving a positive response, Jelesnik urged the Osmonds to go to Hollywood and audition for "The Lawrence Welk Show."

George loaded the four boys in their camper and drove to Los Angeles, only to be stood up by Welk after waiting all day outside his office.

Enter the Lennon family. The Lennon Sisters, four teenagers a few years older than the Osmonds, were a popular singing act on Lawrence Welk’s television show. Their parents, Bill and Sis, let the Osmonds park their camper in front of their home in Beverly Hills. When he learned that Welk had snubbed them, Bill Lennon suggested a plan B.

Lennon was the ring announcer for boxing matches televised locally from Olympic Auditorium in L.A. “Your boys need to be seen; they need to be on TV,” he told George, and offered to let them sing that night at the fights.

Alan Osmond will never forget that gig. He was 12, his brothers 10, 8 and 6. They were dressed alike in barbershop quartet outfits. In the center of the ring, Bill Lennon announced, “From Ogden, Utah, tonight we’ve got the Osmond Brothers,” after which the boys, “scared as mice,” sang “Ragtime Cowboy Joe.”

“Even before we finished, they started booing,” remembers Alan. “‘Get on with the fights!’ they yelled. ‘Go back to Utah!’ They threw beer bottles. We ran off like a bunch of dogs with their tails between their legs.”

That night in the camper, George took a last gasp at salvaging a trip that had so far been a disaster.

“Would you boys like to go to Disneyland tomorrow?” he asked.

Still dressed alike, they walked onto Disneyland’s Main Street the next day and ran into the Dapper Dans, Disney’s resident roving barbershop quartet.

“You look like a barbershop quartet,” the Dapper Dans mused. “Sing us a song.”

The Osmonds literally stopped traffic, including the trolley car that ran up and down Main Street, as a crowd gathered to listen.

When the singing was over, the Dapper Dans took the Osmonds in to meet Tommy Walker, Disneyland’s director of entertainment. When the boys apologized for blocking the street, Walker put his feet up on his desk and laughed. “No, no, I think it’s great,” he said, and turned to George.

Nothing else happens. Nothing. We owe them everything. – Marie Osmond on the influence the Osmond Brothers had on the family's success

“How would your boys like to come back next summer and sing at Disneyland?” he asked.

As soon as school ended in Ogden in 1962, the Osmonds returned. This time Walt Disney himself wanted to meet them. Performing in front of the creator of Mickey Mouse so unnerved 7-year-old Jay that he knocked off his fake mustache. Disney loved it. “Keep it in the act,” he said, and offered the Osmonds a spot on his television show, “Disneyland After Dark.”

When the show aired, among those watching was a man named Jay Williams, who had also happened to see the Osmonds on TV when they sang at the fights. He called his son, who that fall was starting a variety show on NBC.

“You should audition these guys,” he said to Andy Williams. “They’re pretty good.”

One thing led to another and on Dec. 13, 1962, barely five years since their sacrament meeting debut, Alan, Wayne, Merrill and Jay entered America’s living rooms on national television on "The Andy Williams Show."

The family left Ogden and moved to California. The brothers would go to “work” and there’d be Bob Hope on the set, or Sammy Davis Jr. or Tony Bennett or Bill Cosby or Jane Wyman. One time they appeared with Lawrence Welk.

It all happened so fast. They cut albums, they acted in a TV series. Promoters lined up tours at major venues across the country. They went to Sweden, Belgium, New Zealand, Great Britain, France, the Far East.

The Hilton booked them in Las Vegas, where their act ran concurrently with Elvis Presley, who became particularly close with Olive, aka Mother Osmond, who reminded him of his own mother. Jay remembers the day he answered the phone in their suite at the Hilton.

“Hello, is your mother there?”

“Who’s calling?”

“Elvis.”

“Hey Mom, Elvis Presley’s on the phone.”

“Tell him to hold on, I’ll be there in a minute.”

It was Elvis who upgraded the Osmonds' look. “He took us backstage in his dressing room at the Hilton,” says Jay, “opened his closet, showed us his jumpsuits and said, ‘You guys need to macho it up a bit.’ That’s when we went to jumpsuits.”

They met the King and then they met the Queen. Queen Elizabeth II invited the Osmonds to play for her at Buckingham Palace. After the command performance, Alan remembers his mother reaching into her purse and instantly being surrounded by security. Olive Osmond proceeded to carefully pull out a copy of the Book of Mormon and hand it to the queen.

“Well thank you Mrs. Osmond,” Alan remembers the queen saying. “I will put that on my mantel.”

In 1971, just weeks after "The Andy Williams Show" ended its eight-year run, the Osmonds recorded a song that had first been offered to their boy band rivals, the Jackson Five. “One Bad Apple” became the brothers’ first No. 1 record. They finished with four hits in the top 100 for the year, more than the Jacksons and Rolling Stones combined.

They grew up with teenage girls screaming and mobbing their limos and trying to sneak into their hotel rooms. It was the '60s, the Age of Aquarius. But not to George Osmond, it wasn’t. The old Army sergeant never broke character. When his boys’ star started to rise, he pulled out the dictionary, turned to P, and crossed a line through the word "proud."

“We’re taking that one out of your vocabulary,” he announced.

While Olive nurtured (and gave away Books of Mormon), George ran the show. He handled the money and the travel. He lined up top choreographers. He demanded discipline. On the “Andy Williams” set, they became known as “One Take Osmonds” because of their penchant for perfection.

Nor did they veer from their Mormon roots, or hide their beliefs. While none would serve traditional missions — unlike brothers Virl and Tom, who became the LDS Church’s first hearing-impaired full-time missionaries — theirs was a call of significantly longer duration.

In 1976, the family was invited to a dinner at church headquarters in Salt Lake City. Church President Spencer W. Kimball was there, along with several more general authorities and the presidency of the Relief Society. After dinner, President Kimball stood up and announced that church statisticians had determined the Osmonds were responsible for 26,000 baptisms THAT YEAR. He thanked them and proceeded to set apart the entire family as international missionaries, with no expiration date.

• • •

The decline for Alan, Wayne, Merrill and Jay began from within.

Ever since they’d first brought Donny and Marie onto the stage to join them, people had been craning their necks to get a better look. In 1975, ABC bypassed the brothers entirely, asking Donny and Marie to host their own TV show.

The boys could have moved on with their own career. Instead, their father made a command family decision for them: They would become executive directors for the show that would star their 18-year-old teen idol brother and pretty 16-year-old sister. They would make periodic guest appearances, but remain largely in the background.

And they’d be back in Utah to do it — because George Osmond negotiated a deal with ABC that the "Donny & Marie" variety show would be produced in a 100,000-square-foot studio the Osmonds would build in Orem. Not only did the Osmonds come home, they brought Hollywood with them. They settled in and built magnificent houses near the studio on what became Osmond Lane.

Money was not a problem — until it was.

Estimates are that the Osmonds were worth anywhere from $70 million to $100 million in the late 1970s. They owned their studio, their houses, a condominium on Santa Monica Boulevard in Los Angeles, a ranch outside Ogden in Huntsville, an apartment complex across from BYU in Provo. They’d started their own real estate company, they had endorsement deals, they had record royalties pouring in.

But with all the diversification came business partners, including more than one or two who would wind up in prison for fraud and embezzlement. One man, a Catholic, posed as a Mormon to gain the family’s confidence before bilking them out of millions.

Long sad story short: By 1983 the Osmonds were broke. Cleaned out. Destitute. All the financial experts said they should take out bankruptcy and start over.

Every financial expert, that is, but George.

Father Osmond said nothing doing. No bankruptcy. They would pay every bill they owed.

They sold their houses, their studio, the Riviera Apartments in Provo, their cars. And when that wasn’t enough, George sent them all out on the road to sing.

For Alan, Wayne, Merrill and Jay it was back to playing county fairs and corporate retreats and casinos. They might not be as popular as they once were — they might not be Donny and Marie — but they could still draw a crowd.

No one stopped singing until every last debt was paid.

• • •

Adversity of a more personal sort came in 1987 when Alan, at 38, was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. In 1997 Wayne, at 46, underwent surgery for a cancerous brain tumor.

Neither Alan nor Wayne stopped performing for long, and from 1992 through 2002 the brothers relocated to Branson, Missouri, where in different configurations, including younger brother Jimmy, they performed in the Osmond Family Theatre and slept in their own beds at night.

In 2008, shortly after Olive (2004) and George (2007) passed away, Alan, Wayne, Merrill and Jay joined the entire Osmond family for a 50-year anniversary farewell tour that culminated at the Conference Center in Salt Lake City.

Which brings us to 2018. Where are the original Osmonds now?

• Alan, who turned 69 in June, lives in Orem with Suzanne, his wife of 44 years. His movements are hindered, but he remains unbowed. “I have MS; MS doesn’t have me,” he says.

Still active as a songwriter, Alan is currently working on a song for Orem’s 100-year celebration in 2019. He and Suzanne stay busy and then some keeping track of their nine children, all boys, and 28 grandchildren. They live in a comfortable home, though nothing like the 17,000-square-foot house they once occupied on Osmond Lane.

Of the dark days when the Osmonds lost their fortune, Alan declines to name names of those who took advantage of them, even those who went to jail. “No one’s going to point fingers because we’ve forgiven everybody,” he says. “If you can’t say good things about your neighbor don’t say anything at all; that’s how we were raised.”

• Wayne, who turned 67 on Aug. 28, lives with his wife Kathy in Bountiful, where he stays busy working in his yard and spoiling his grandchildren. His brain cancer hasn’t returned since 1997, but the treatments needed to stop it resulted in an almost total loss of hearing.

The hearing loss is in no way related to the deafness his older brothers Virl and Tom were born with. Theirs was genetic. His is due to massive radiation doses that “ate up my cochlea.”

“It’s funny, and really ironic,” Wayne reflects, “but I had the best ears in our family. Whenever my brothers wanted the instruments tuned I was the one they turned to.”

In 2012, when he was 61, Wayne suffered a major stroke. He confesses to missing playing the guitar like he once did — back in the day when his skills were compared to Jimmy Page.

He values his privacy (he preferred not to have his picture taken) and lives on Social Security and says it’s enough. The long-ago financial setback, he says, “actually made me love my Heavenly Father more because it made me realize money doesn’t do anything; it means nothing.

“I’ve had a wonderful life. And you know, being able to hear is not all that it’s cracked up to be, it really isn’t. My favorite thing now is to take care of my yard. I turn my hearing aids off, deaf as a doorknob, tune everything out, it’s really joyful.”

• Merrill, 65, lives in St. George with his wife Mary. Last year he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Dixie State University, recognizing his humanitarian efforts. If the Osmonds had a John Lennon, it was Merrill (to Alan’s Paul McCartney). He wrote or co-wrote with Alan many of their songs and, before Donny took center stage, sang lead on almost all of their hits. To distinguish himself from his teen idol little brother, Merrill let his hair turn white.

“We were raised like Marines,” remembers Merrill. “Unlike a Joe Jackson (the Jackson 5 patriarch), our dad was loving but he was military. We lived in barracks, we had our bunk beds, our shelves where everything had to be neat and clean. When we rehearsed we toed the line. I don’t know that I’d recommend that lifestyle to anybody, but I don’t think we’d have been able to accomplish what we’ve done for the past 60 years if not for the dad that we had and a very angelic mother. It was because of them, and the church, that kept us grounded.”

The world would never have heard about the singing Osmonds, he says, if not for his deaf older brothers. “That’s the untold story. We were not very rich and we had to go out and make money for two deaf brothers.”

For Merrill, the beat goes on. He and Jay — the last of the original Osmonds still in the saddle — have formed a two-man act that has bookings this fall and winter in the U.S. and Europe. They perform their vintage hits along with a few new ones and travel and sleep in a touring bus like the old days, which suits Merrill just fine. “Give me my little space I can crawl into,” he says, “and I’m happy.”

• Jay, the little brother who once charmed Walt Disney by losing his fake mustache, has a permanent mustache now. He lives in Mesa, Arizona, with his wife Karen. He turned 63 in March. His most profound memory of being an Osmond Brother was when the director on "The Andy Williams Show" set turned to the boys just before they took the stage for the first time in 1962 and said: “Don’t make a mistake; 40 million people are watching you.”

Jay was 7 years old.

“I’ll never forget that,” he says. “We were under such high stress, always.”

Nor will he forget the night President Spencer W. Kimball called the Osmond family on a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. “That was a game changer for me,” he says. “That pretty well told us that what we were doing was very profound for families in the world.”

But being perfect takes its toll. “I call it Osmonditis,” he says, “learning to please everyone, to entertain everyone. It’s not easy.”

Jay looks at older brothers Alan and Wayne and, despite their health challenges, observes, “Those guys are extremely content with where their life is. The pressure’s off and they can live the way they want. I’ve never seen them happier.”

Performing with Merrill has put a bounce in Jay’s step. “We’re doing our own thing,” he says, “and there’s nothing quite like the feeling of getting up and singing our songs and seeing people out there smiling. That never gets old. I’m going to continue on singing and hopefully bless people’s lives.” Having said that, he turns to his brother: “We can do this the rest of our lives, can’t we Merrill?”

• • •

The original Osmonds have no bigger fan than their sister Marie. The day she was born, Oct. 13, 1959, the four brothers gathered outside her hospital room at the Dee Hospital in Ogden and serenaded her with “I Want a Girl.”

To pay tribute to her big brothers, Marie organized a concert in Hawaii that was held, appropriately, on Oct. 13 in the Blaisdell Arena in Honolulu.

She talked Alan and Wayne out of retirement to join Merrill and Jay on stage one more time. Alan’s son David also performed, along of course with Marie.

“I wanted to honor my four original brothers that started everything,” she said. “My brothers are legendary. Go listen to their harmony (from the old days), it’s mind-boggling. I have spent a lifetime studying and learning singing, but I promise you I have never heard anybody sing like my four original brothers.”

Proceeds from the concert went to the brothers.

“I wanted nothing from it, so is it helping them out financially? I hope so,” she said. “But more than anything I wanted to honor them. I think my mother was putting the thoughts in my head to do this, and my father — I’m not kidding.

“My brothers are my heroes. Everything I have learned from a professional standpoint, from having honesty and integrity and doing what’s right, I learned from them. These are strong men, and I love them.”