- Foodborne illnesses peak during June, July and August, accounting for one-third of all such illnesses in the U.S.

- Campylobacter and salmonella are the most commonly reported, linked to contaminated meats, eggs, unpasteurized dairy and fresh produce.

- The Northern Plains and Upper Midwest have the highest incidence, and South Dakota has double the national average of cases.

Summer — and August in particular — provides a feast not only for friends and families having outdoor barbecues and parties, but for the bacteria and even parasites that thrive on meat and produce that are left out too long or handled improperly.

One-third of all foodborne illnesses in the U.S. are reported in June, July and August, according to a new report from Trace One, a regulatory compliance company for the food and beverage industry. The company based its findings on national estimates and four years of finalized state-level data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, looking at the most commonly tracked foodborne pathogens. It also looked at how illness incidence varies throughout the year and which states have higher rates of foodborne illness.

“We conducted this analysis to highlight the seasonal spike in foodborne illnesses during the summer months. With warmer temperatures and more outdoor food handling, the risk of contamination increases dramatically — making it the ideal time to raise awareness about regional trends and reinforce food safety," Erika Redaelli, Trace One’s global head of solution management, regulatory and scientific affairs, told Deseret News.

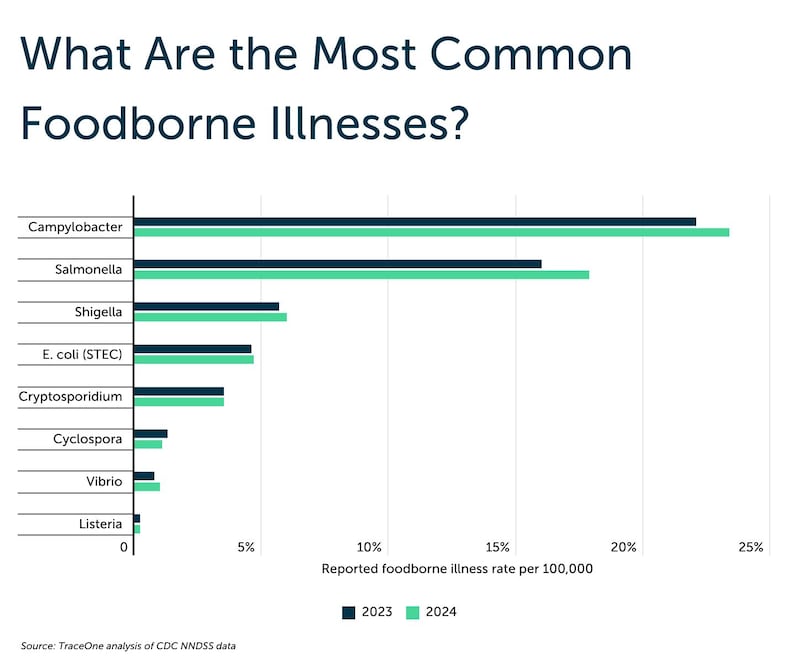

The illnesses they looked at, in the order in which they occur nationally, are campylobacter, salmonella, shigella, E. coli, cryptosporidium, cyclospora, vibrio and listeria. These are also common reasons for food recalls.

Campylobacter and salmonella are “by far the most frequently reported,” per the report, commonly linked to contaminated retail meat, eggs, unpasteurized dairy products and fresh produce. In 2024, the campylobacter rate was 23.4 cases per 100,000 people, which was an increase from 2023’s 22.1 cases. Salmonella’s rate was 17.9 cases per 100,000, up from 16 cases per 100,000 people in 2023.

The others are less common, but as the report notes, “infections linked to listeria and vibrio are often more severe and can result in hospitalization or death, particularly among vulnerable populations.”

The report says that while most symptoms of foodborne illness — typically diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal cramps and fever — are mild and resolve on their own, they can cause serious complications including blood infections and kidney failure, particularly in vulnerable populations like young children, older adults and those with compromised immune systems.

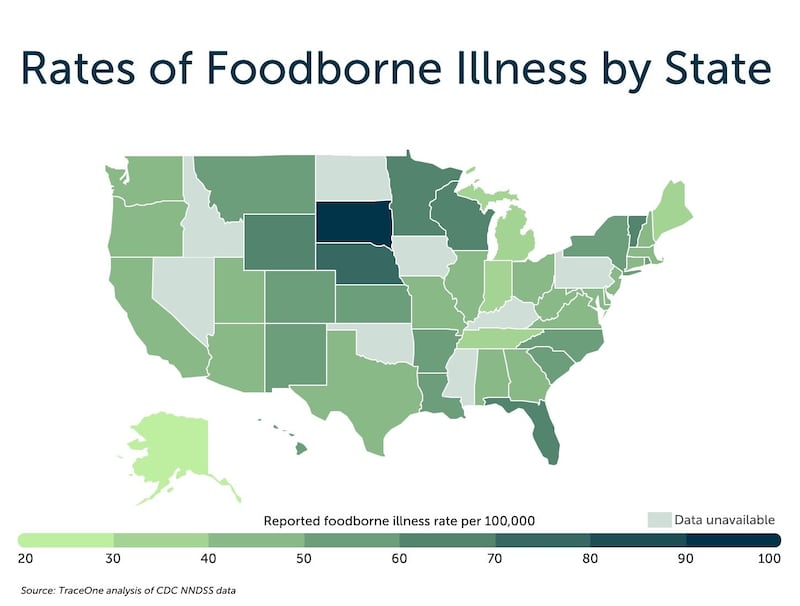

The report only considers the 42 states that had complete data for all eight of the tracked pathogens. It acknowledges that differences in access to testing, public health infrastructure and reporting and whether people seek medical care impacts the illness rates it tracks.

Illness varies state to state

Utah was near the bottom of the pack, coming in at No. 32 out of the 42 states considered, with 1,412 cases of foodborne illness on average reported each year included in the analysis, for a rate of 43.2 cases per 100,000 people. The most reported pathogen in Utah’s cases was cryptosporidium, a “microscopic parasite that spreads through contaminated water or food and often causes prolonged gastrointestinal symptoms,” per the report.

Trace One reports that the Northern Plains and Upper Midwest have “notably higher incidence” of foodborne illness. South Dakota leads the way, with more than twice the national average of cases at 92.2 per 100,000 people, followed by Nebraska (74.4), Minnesota (66.6), and Wyoming (66.4).

It could be in part exposure, but also perhaps better diagnostic testing and reporting, per the report.

“In contrast, several other high-ranking states are geographically and demographically diverse. Vermont (62.0), Florida (61.9), and Wisconsin (60.5) also reported elevated rates, as did parts of the Mountain West such as Montana (59.7) and New Mexico (58.8). Larger states like New York (58.3) and California (48.9) fell near the national average but still ranked among the top half of states.”

Alaska (27.0) had the lowest rate of foodborne illness, just ahead of Michigan (33.3), Maine (33.6), Indiana (33.7) and Tennessee (37.8).

Enjoy food without nasty aftermath

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration reports that bacteria in food multiply more quickly at temperatures between 40° F and 140° F, which contributes to the surge in cases in summer months.

Here are FDA tips to keep food safe so you can enjoy it without lingering problems:

- Wash your hands, well and often, with soap and water. If you are outdoors without a fresh source of water, make sure you have a water jug of clean water on hand, along with soap and paper towels. You could also use disposable moist towelettes to clean your hands.

- Separate raw and cooked food. No cross-contaminating by putting food that’s cooked on a plate or surface that held raw food without thoroughly cleaning it first. Don’t use the same utensils for both, either, without cleaning them.

- Marinate food in the fridge, not on the counter. And don’t use that marinade you soaked raw food in on food that has been cooked — set some aside upfront in the process.

- Cook food to the right temperature. Don’t guess; use a food thermometer. Burgers should be cooked until the pink is gone. They need to reach 160° F. Chicken needs to reach at least 165° F. If you partially cook food so it takes less time on the grill, go straight from pre-cooking it to the grill. Don’t let it sit on the side, where bacteria can multiply.

- Don’t leave food out for more than two hours. And if it’s 90° F outside, an hour is the safe limit.

- Keep hot food hot, at or above 140° F. You can use an insulated container. And pay attention to how long ago the food was cooked.

- Keep cold food cold, at or below 40° F.