If 2023 first-overall pick Connor Bedard had gone to college, would he have been more ready for his first NHL season?

That is, in essence, the question promising young hockey players are asking themselves with the ground now shifting in the NCAA eligibility world. It’s not that Bedard hasn’t been successful, but the domination that he had in the Western Hockey League just has yet to manifest itself in the 20-year-old’s NHL career thus far.

If you want to make it to the NBA, NFL or MLB, you almost always have to go through the American collegiate system to get there. But until now, it hasn’t been like that in hockey.

Yes, the NCAA has Division I programs that frequently propel players to the NHL, but there are two other routes that are just as effective: Canadian major-junior and European professional hockey.

It has long been debated which path is the best to take, and now that the NCAA has changed its eligibility rules, the debate becomes even more important.

The NCAA rule change

Until now, anyone who had played Canadian major junior hockey lost their NCAA eligibility. Although major junior players get paid nothing more than a stipend and a scholarship, the NCAA considered the Canadian Hockey League professional. Starting in 2025-26, that’s no longer the case.

The rule change opened up a whole new development path for CHL players, and many have already taken advantage of the opportunity.

Gavin McKenna, a 17-year-old phenom who spent the last three seasons with the WHL’s Medicine Hat Tigers, is among them. He committed to Penn State in July, becoming the highest-profile NCAA recruit ever.

“I think it honestly just makes the jump (to the NHL) easier, going against older, heavier, stronger guys,” McKenna said after announcing his decision. “I think it really prepares you. Even in the locker room, being around older guys, being around more mature guys, I think it’ll help me a lot.”

McKenna also happens to be a distant cousin of Bedard’s. He said he’s able to use Bedard for advice, meaning he may have been included in the conversation as to which league to play in.

While many players have already switched to the NCAA, there’s still something to be said for the CHL.

Of the 596 skaters who played half the NHL season or more last year, as well as the top 64 goalies in terms of games played, the CHL produced more than any other league:

- 40% came through the CHL

- 29% came through the NCAA

- 24% came through European professional leagues

- 6% played in multiple of the above leagues

- Two players came directly from the USHL

The argument for the NCAA is that it prepares players better for the NHL game. The competition is older, and therefore bigger, stronger and more developed skill-wise.

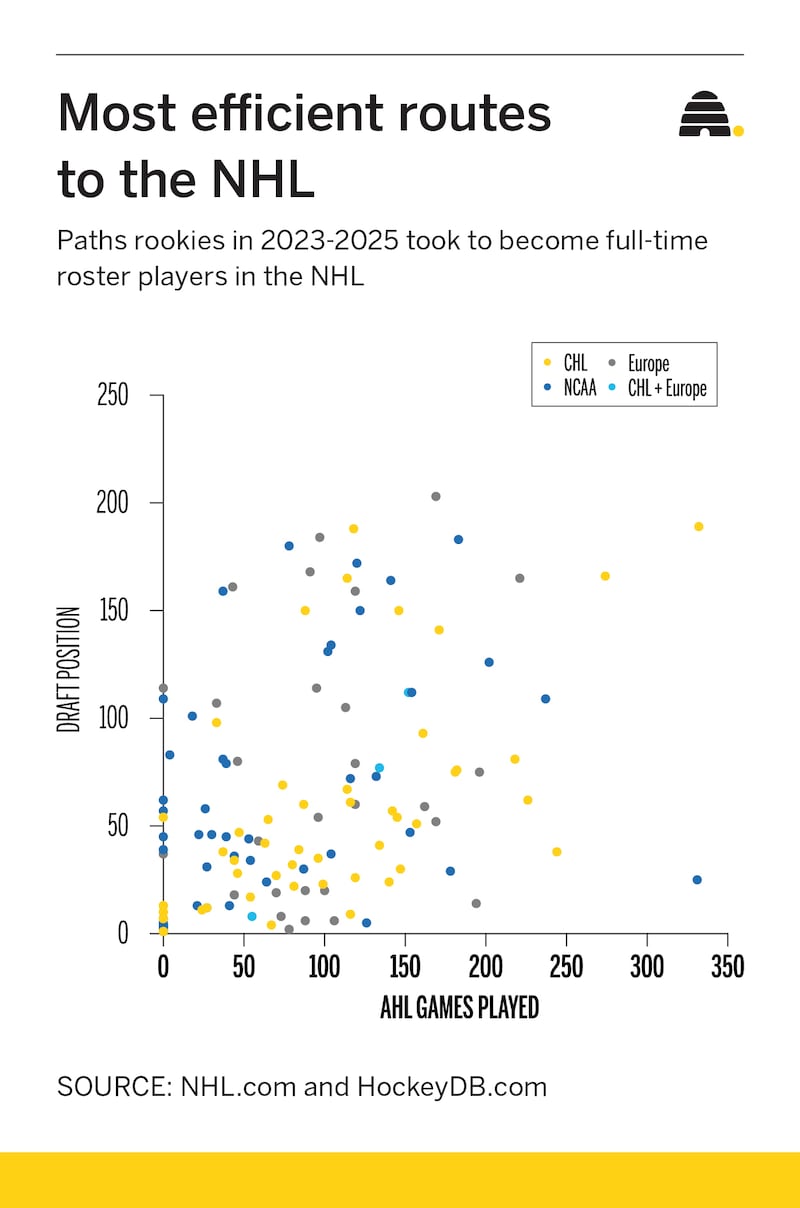

That’s characterized by the number of American Hockey League games NCAA players need to play before becoming full-time NHLers. Over the last two years, players who played enough games to break their rookie status averaged 34% fewer AHL games to get there, compared to those coming from the CHL.

That’s in spite of the fact that among those players, the CHL group had the lower average draft position: 59, compared to the NCAA’s 67.

In that same span, 11 players from the NCAA broke into the league without seeing a single game of AHL action. The CHL had just five.

“I think it’s the greatest thing I’ve ever seen in hockey, to be able to play in junior hockey in Canada and then go get an education at Boston College or (Boston University),” he said. “My son went through the process of playing in the USHL and then going and being a DI player, and I always thought if that was ever available to the Canadian kids, it’s a game-changer.”

— Bill Armstrong, Utah Mammoth general manager

If a player coming out of the NCAA is more NHL-ready than one coming from the CHL, that’s a major reason for top prospects to go there.

As both an NHL executive and a hockey dad, Utah Mammoth general manager Bill Armstrong is in favor of CHL players moving to the NCAA.

“I think it’s the greatest thing I’ve ever seen in hockey, to be able to play in junior hockey in Canada and then go get an education at Boston College or (Boston University),” he said. “My son went through the process of playing in the USHL and then going and being a DI player, and I always thought if that was ever available to the Canadian kids, it’s a game-changer.”

The NCAA isn’t necessarily the best choice for everyone

James Hagens, who was long thought to be the 2025 first-overall pick, fell to seventh after a relatively underwhelming season at Boston College. He’d previously played at the United States National Team Development Program, where he’d tied none other than Patrick Kane for eighth-most single-season points in the program’s history — so the expectations of him were high.

Similarly, 2024 25th-overall pick Dean Letourneau went straight from high school prep hockey (where he scored 127 points in 56 games) to the NCAA, where he managed just three assists in 36 contests. He was originally set to spend that season in the United States Hockey League, but when a spot at Boston College opened up at the last minute, he went there instead.

That’s to say the NCAA isn’t for everyone. If you aren’t ready, it can chew you up and spit you out, and in many cases leave you worse off than you otherwise would have been.

Other factors in the decision

The on-ice debate is important for the best young hockey players, but realistically, very few from either league end up as full-time NHLers. Those who are less likely to make their careers out of hockey should take the postsecondary education aspect just as seriously as the on-ice component.

Until now, each NCAA team could only give out 18 full-ride scholarships — but that increases to 26 this coming season. That means that every player on the roster is eligible to receive one.

The CHL also offers full-ride scholarships to its alumni. Each year a player spends in the league earns him a year of tuition and books.

Other factors include the quality and accessibility of training grounds (which are generally better in the NCAA) and NIL money.

NIL money might not be as big of a factor in hockey as some would assume. International students who hold “F-1″ visas are allowed to work on campus and nowhere else. Because NIL money comes from external sponsors, players from Canada and Europe are not allowed to receive it.

Schools can, however, seek NIL sponsors in the players’ respective home countries.

One advantage to playing in the CHL is the pro-like schedule. While the NCAA season consists of 34 regular season games, CHL teams play 68. Players often say one of the biggest adjustments to the pro game is learning how to play nearly every other day. Playing in the CHL schedule can make that transition easier.

How does the NCAA rule change affect junior leagues?

CHL

It’s not unlikely that virtually every top North American prospect will go to the CHL, now that there’s no reason to hold out for college. In that sense, the CHL could benefit greatly from the rule change (even though they’ll likely lose the bulk of their top players to college around age 18).

It could also be the start of a rapid American CHL expansion. There are already nine teams from the southern side of the 49th parallel, but they’re all located within a few hours of the border. Adding an American league could influence more kids to play there.

There has been speculation that the USHL could consider joining the CHL as its fourth member league. While it’s a lower level of hockey right now, the playing field could be evened out if the two sides were to join forces.

Junior-A leagues

Until now, players who wanted to keep their NCAA eligibility typically competed in Junior-A leagues until they graduated from high school. The British Columbia Hockey League, the Alberta Junior Hockey League and USHL had especially made names for themselves for that reason.

With college hopefuls now able to go to the CHL (a much higher level than Junior-A), those leagues could drop to the same level as the North American Hockey League and the National Collegiate Development Conference — essentially college prep leagues for players who don’t necessarily have higher offers.

That being said, it might not hurt those leagues as much as one might think.

Particularly in Canada, junior leagues are the beating hearts of their respective communities. Most of the teams reside in smaller cities, so catching a game is one of the only things to do on, say, a Friday night — not unlike high school football in American communities.

The fans don’t always care about how good the hockey is. It’s more about having a fun night out, and as long as the teams can still provide that, people’s desire to attend games shouldn’t change.

That’s definitely the case in Idaho Falls, Idaho, where the Spud Kings reign supreme.

USNTDP

The USNTDP has long been the premier system for developing American hockey players. Its teams compete against both USHL and NCAA teams while they’re still in high school, after which the majority of them head to DI colleges.

How the change will affect that program is yet to be determined, but the option to play in the CHL and then go to college might be too good to pass up.

Last year, the CHL’s best players topped the USNTDP handily. They played two games against each other and the CHL won both, with a cumulative score of 9-3. The mass exodus of elite CHL players could change that — the 2025 CHL USA Prospects Challenge will provide an answer.

Other consequences of the rule change

New NHL/CHL agreement

The new collective bargaining agreement, which takes effect in 2026-27, will allow each NHL team to assign one 19-year-old to the AHL (pending agreement from the CHL).

The current rule restricts those players from playing in the AHL before age 20 or until they’ve played four CHL seasons, whichever comes first. They can go directly to the NHL, but if they don’t stick around, they’re obligated to go back to junior hockey.

This is significant for players who are too good for the decreasing talent in the CHL, are ineligible to go to the NCAA because they’ve already signed entry-level NHL contracts and aren’t quite NHL-ready. Mammoth prospects Tij Iginla and Cole Beaudoin, for example, are in that boat this season, though the rule change won’t take effect until it no longer applies to them.

Of course, taking the NCAA route does allow players to play in the AHL at age 19, which can be beneficial for some players, but once you leave the NCAA for pro hockey, you can’t go back — and many players won’t be willing to leave college early for any league but the NHL.

Standardization of draft rights

Another change enacted by the new CBA is the standardization of player rights after being drafted.

Currently, the amount of time a team retains a player’s rights depends on the league the player was in when he was drafted. Starting in 2026-27, teams will keep every player’s rights for four years, regardless of circumstances.

This makes things simpler while also eliminating the need for teams to rush to sign their CHL-drafted players, whose rights they retain for only two years under the current system. Had this change happened sooner, Justin Kipkie would still be a member of the Mammoth, rather than being redrafted by the Minnesota Wild.

Moving the draft age

It’s far from official, but there has been speculation that the NHL might consider switching to a 19-year-old draft, rather than the current 18-year-old system.

This would give teams the opportunity to see more draft-eligible prospects play at the NCAA level, as many of them aren’t old enough to play in college before being drafted under the current system. It also would result in more drafted players making it to the NHL because they’d be that much closer to their actual selves when they’re drafted, rather than 18-year-olds just graduating from high school.

If that happens, it’s likely that the draft is shortened, too. If teams get more accurate looks at their potential prospects, making picks will be less like throwing darts at a board. The draft has been shortened several times in the past, and it could happen again.

Probable result (for now)

As of now, it seems that the most likely result of the change is a standardized route to the NHL for the top North American players. It should look something like this:

- 16-18 years old: CHL

- 18-20 and older: NCAA

- Whenever the player is deemed ready: AHL or NHL