At its best, America is about more than innovation and ambition. Its promise of exceptionalism is rooted in its generosity — to welcome the stranger, to believe all are created equal, or, as the Book of Matthew puts it: to feed the hungry, clothe the naked and to care for the least among us.

The biblical call to our higher angels, enshrined in our Declaration of Independence, has faced challenges in recent years, as public life has grown more fractured, isolated and even nihilistic. For whatever reason, the ethic of noblesse oblige — the understanding that to whom much is given, much is required — has faded from view, or importance. At a time when many feel pulled to focus inward, we are called to remember and renew the generosity of spirit that has always been one of our most powerful national traits.

To that end, this is the magazine’s first Philanthropy Issue, and something we’re calling The Deseret 50. To be clear, this is not a ranking, but rather a collection, in no particular order, of examples of giving worthy of emulating. The people, organizations and ideas highlighted here are game-changers in the world of giving — and not just in our community and across the West, but around the world. They are proof that generosity is not only alive and well, but evolving.

Take for example Christena Huntsman Durham, who turned her family foundation’s attention to mental health, pledging $150 million to erase stigma and expand care. Or MacKenzie Scott, who has upended the norms of big-money giving by trusting organizations to use her billions without strings attached.

Philanthropy, of course, has always been about more than family fortunes. Hali Lee has taken the Korean tradition of giving circles, pooling modest contributions into transformative support, and scaled it to more than $1 million in small grants for artistic and cultural products by people of Asian American and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Island ancestry. It’s a movement that’s gone supernova: One study found that from 2017 to 2023, nearly 4,000 giving circles in the U.S. donated a staggering $3.1 billion to charity.

Here in Utah, there are many innovators and trailblazers in the world of philanthropy, but when it comes to reinventing how we think about giving, perhaps no one has had a bigger impact than Kristin Andrus, whose message is that giving is as much about time as it is money, maybe even more so. She rallies Utah mothers to volunteer, weed gardens, assemble backpacks for refugees and distribute hygiene products to those who need them most.

Across these pages, you’ll also find stories of grassroots collaboration and large-scale vision: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, coordinating humanitarian relief in more than 190 countries; Jim Sorenson aligning every dollar of his foundation with its innovative mission; Hanna Skandera channeling a sports legend’s legacy into youth opportunity; and organizations like Utah’s Promise or Benefit Chicago proving the power of collective action.

The point is not to revere generosity as a rarefied act. It is to recognize that what has been called charity or service is, in fact, a fundamental human act, a natural impulse, even. A duty, yes, a responsibility and an opportunity open to all of us, to be sure, but also a blessing, one that enriches the giver as much as the recipient. We can give our skills, our patience, our attention. We can give locally or globally. We can give in ways seen and unseen.

The ethic we celebrate in this issue, then, is not charity as a performance, but generosity as a way of life. “The deed is everything,” Goethe said. “The glory is naught.”

At a time when so much pulls us apart, giving may be one of the surest ways to bring us back together. — Jesse Hyde

Christena Huntsman Durham

Christena Huntsman Durham grew up watching her father, Jon Huntsman Sr., give back to the community faster than he could make money. “His drive to make money was to give it away,” she says. “He wanted to make a difference because he saw all the good that came from it.”

Huntsman Sr. was part of the original Giving Pledge with Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, and his generosity made a difference in countless lives. Those early lessons in giving back stuck with Durham as she raised her seven children. When Huntsman Sr. died, his foundation, which had largely focused on finding a cure to cancer, was turned over to the next generation. Durham and her siblings were tasked with finding the “cancer of their generation” — and they chose mental health.

“Mental health is so different than cancer,” Durham says. “You keep it close to your heart because the stigma is so great. You don’t share what you’re going through.”

The result was a $150 million pledge to the Huntsman Mental Health Institute, a first-of-its-kind facility dedicated to researching the genetic links to suicide and substance use. “We are proud to raise our hand and say, ‘This is in our family. This has been generational,’” Durham says. “I think at some point in all of our lives, we will be touched by mental health. We will either be picked up off the floor ourselves, or we’ll pick somebody else up off the floor.”

Durham is passionate about eliminating mental health stigma and ensuring everyone has access to the care they need. She urges every Utahn to download the SafeUT app, which provides 24/7 access to crisis counseling, and she’s working to bring that model to other states.

“We don’t have 30 years to figure this out. We are in crisis mode. Until we look at mental health and substance use as a brain disease, that’s not going to change,” Durham says. “We want to give people hope. We want them to know there are treatments and cures.” — Mekenna Malan

Mackenzie Scott

MacKenzie Scott has only needed six years to become the most disruptive force the philanthropy world has ever seen. In May 2019, she also signed the Giving Pledge, promising to gift at least half of her wealth to philanthropic causes. The following year, she debuted at No. 4 on Forbes’ “richest women in the world” list, worth $36 billion, and got to work. She has since donated nearly $20 billion through her foundation, Yield Giving, whose minimalist website offers two definitions of the word “yield”: “1. to increase 2. to give up control.” Taken together, those six words sum up Scott’s seemingly simple, functionally revolutionary approach to philanthropy: Give talented people resources, and get the heck out of the way.

Generally speaking, philanthropy can be very bureaucratic. There are reporting requirements and layers of oversight. Many want a say in how the money is spent, and everyone expects to see progress reports. These hurdles are often well intentioned, designed to limit abuses and fraud. But Scott sidesteps them by vetting organizations personally, with the help of a small team, before giving away large sums with no strings attached. The idea, called “trust-based philanthropy,” gives proven and promising organizations the resources they need without any handholding. “I needn’t ask those I care about what to say to them, or what to do for them,” Scott wrote in a 2022 blog post. “I can share what I have with them to stand behind them as they speak and act for themselves.”

Time magazine wrote earlier this year that Scott is “rewriting the rules of philanthropy.” That’s true in a seismic, foundational sort of way — but also in a stylistic way. Scott announces annual donations in blog posts on Yield Giving’s website, often accompanied by some personal musings and a poem, or an inspirational quote. Beyond that, she’s completely silent about her giving. Her website says, in explicit terms, that she chooses “not to participate in events or media stories,” and that “opportunities for public recognition or attention” should be directed toward individual nonprofits. Even her methods for finding nonprofits to fund are hush-hush. In 2024, she did have an open call for applications, but most of Yield Giving’s recipients have been chosen via “Quiet Research” — an opaque process that is completed “as privately and anonymously” as possible to “limit burden,” and that culminates in Yield Giving reaching out to chosen organizations “to tell them we admire what they are doing and would like to give them an immediate gift for use however they choose.” It’s that easy. And, for a long-entrenched philanthropy elite, that is hard.

Scott’s philanthropy speaks for itself in terms of sheer volume and impact — a study released earlier this year by The Center for Effective Philanthropy found her strategy has had net-positive effects — but her approach also shares some similarities with her past occupation of writing novels. Like a great work of literary fiction, her giving is sweeping in scope — but also subtle, even vague. She doesn’t explain herself because she doesn’t have to. The disruptive words on the page, so to speak, speak for themselves. — Ethan Bauer

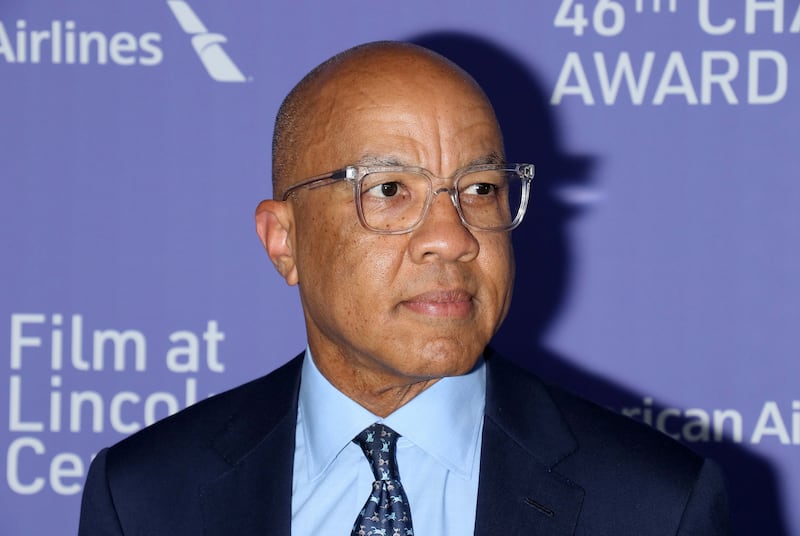

Darren Walker

Before Darren Walker became president of the Ford Foundation, a $16 billion philanthropic organization and one of the foremost social justice organizations in the world, he was a beneficiary of publicly and philanthropically funded assistance programs. Walker was born to a single mother in a charity hospital. He lived in a shotgun house on an unpaved road in Texas. In preschool, he was selected for the Head Start program, aimed at reducing poverty. He relied on a Pell Grant and scholarships to earn his undergraduate and law degrees. He has called his experience a “mobility escalator,” a firsthand account of how organizations aimed at improving social good can alter the trajectory of a person’s life. And he’s committed his professional life to paying those opportunities forward.

Walker worked as a lawyer on Wall Street before entering the philanthropic field through organizations like the Rockefeller Foundation, where he oversaw the Rebuild New Orleans initiative following Hurricane Katrina, and the Abyssinian Development Corporation, where he worked to build affordable housing in Harlem. As president of the Ford Foundation, Walker created a $1 billion social bond to sustain nonprofits during the uncertainty of the Covid-19 pandemic, making the foundation the first in history to do so.

Though he’s stepping down as president at the end of the year, his impact will leave a lasting mark on the Ford Foundation through the grants he spearheaded to further issues like criminal justice reform and arts and culture initiatives, which earned him the National Humanities Medal in 2023. “The reason I’m so singularly focused on inequality today is because I want little boys and girls, wherever they are, if they’re living in housing projects in the Bronx and they’re Black or Brown or they’re living in rural towns that have been ravaged by opioids, I want them to be able to dream and to feel as I did,” he told Stanford Business in March, “that America wants you to succeed, your country is enabling you to be a success and to get on the mobility escalator.” — Natalia Galicza

Steve Young

During the early days of Steve Young’s Hall of Fame career with the San Francisco 49ers, the legendary BYU quarterback attended a talk given by writer Stephen Covey. The bestselling author of “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People” shared some wisdom Young still thinks about often: “If you want to change the world,” Covey said, “you need to change a kid’s life.” That idea led Young to found the Forever Young Foundation way back in 1993 — right between his two MVP seasons; two years before his third and final Super Bowl; and six years before his retirement.

Funded in large part by charity golf tournaments and corporate sponsorship, the Forever Young Foundation operates a range of youth-oriented services in the United States and Ghana, from mental health campaigns to tech accessibility to music therapy. One sports complex the foundation built in Ghana in the mid-2000s led to the discovery of Ezekiel “Ziggy” Ansah, who dominated on the newly constructed soccer field, befriended some Latter-day Saint missionaries, joined the church and eventually enrolled at BYU, where he walked onto the football team in 2010 and became the fifth-overall pick in the 2012 NFL draft. That’s Young’s “favorite piece of foundation trivia,” he told Golf Digest in 2019. But it’s also emblematic of how impactful — and unexpected — philanthropy can be.

He’s especially proud of the foundation’s longevity as it winds through Year 32. It maintains a four-star rating with Charity Navigator — the top score possible — and continues to expand. In July, it opened its ninth location of “Sophie’s Place” — the foundation’s flagship music therapy program — at the Intermountain Primary Children’s Hospital, Miller Family Campus in Lehi. Young himself attended and helped snip the ribbon, singing the praises of music therapy’s promise. The event recalled the advice he got from Steven Covey — and something else he told Golf Digest in 2019, a long way from the foundation’s forging. “We’re not the largest children’s charity,” he said then, “but I think we’re one of the best.” — EB

Latter-day Saint humanitarian services

the humanitarian aid efforts of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has grown into a vast global operation that reaches far beyond Utah. Its mission is simple: relieve suffering, foster self-reliance, and provide opportunities for service. But the scale is staggering. In 2023 alone, the organization reported more than 4,000 projects across 191 countries and territories.

The church funds maternal and newborn care programs in sub-Saharan Africa, provides emergency response following hurricanes and earthquakes, and coordinates food security projects from Latin America to Southeast Asia. Its approach reflects the church’s institutional pragmatism: carefully structured collaborations with established NGOs — think UNICEF, the Red Cross, and Catholic Relief Services — rather than going it alone.

That collaboration model is strategic. By piggybacking on existing networks, the church is able to mobilize resources quickly, often funneling millions of dollars into relief efforts within days of a disaster. The result is both efficiency and reach. When war in Ukraine displaced millions in 2022, the church sent food, clothing, and hygiene kits to refugee camps in Poland and Romania within weeks, largely through partner agencies.

Within the humanitarian sector, church humanitarian aid is respected for its consistency and reliability. Its wheelchairs, clean water systems, and neonatal resuscitation training programs aren’t one-off publicity stunts; they’re decades-long commitments that have created measurable impact. — JH

Robert F. Smith

Standing at a lectern in a crimson robe, Robert F. Smith had a surprise for the 2019 graduates of Morehouse College, a historically Black college in Atlanta. He saved it for the very end, but it was worth waiting for. “My family is making a grant to eliminate their student loans,” he said. “Because we are enough to take care of our own community. We are enough to ensure we have all the opportunities of the American dream.” Smith would know. He’s the founding CEO of Vista Equity Partners, a software-focused private equity firm that manages over $100 billion in assets. Smith himself is worth over $10 billion. That one-time debt forgiveness pledge cost around $34 million, but Smith wasn’t done.

Over the past 11 years, he’s given hundreds of millions to a wide range of causes including education, social justice and cultural and environmental preservation. His philanthropic organization, the Fund II Foundation, specifically focuses on grants to charities that “improve the daily lives and long-term potential of those in Black and Brown communities.” During his speech at Morehouse, he closed by imploring the graduates to follow his lead. “Let’s make sure,” he said, “every class has the same opportunity going forward.” — EB

Kristin Andrus

Kristin Andrus believes in getting her hands dirty and her heart broken as often as possible. It’s a mantra that’s guided her and her family toward volunteer work and charitable giving for years. It’s what she told herself when she founded SisterGoods in 2020, a grassroots organization that distributes seven million free menstrual products each year through the Utah Food Bank. And it’s what she continues to tell herself now, as founder of Gathering for Impact, a family foundation that offers quarterly boot camps for women across the state to connect with nonprofit organizations and learn how they can best serve their own communities.

The central mission behind Gathering for Impact, Andrus says, is proving that anyone can make a difference. It doesn’t require billions of dollars or a Rolodex of prestigious connections. All it requires is passion and a knowledge of where to start. “I would find fun, unique, easily accessible ways for families to give back, and then invite women and kids to come with us and do it. … I think what was attractive to families was that this isn’t about writing a check.

This isn’t about how much you are giving to a local nonprofit,” she says. “Everybody wants to help. They just don’t know how to do it. And so when you offer a place, a way to donate or to buy supplies, or whatever it may be, it creates this beautiful community.” Andrus shows women and families how to create tangible change, like gathering hundreds of women to assemble and donate backpacks of supplies to refugee families.

Whether fundraising tens of thousands of dollars in donations for the Christmas Box House — an emergency shelter for youth experiencing abuse, neglect or homelessness — or simply pulling weeds with community members, Andrus works to make philanthropy accessible for women across Utah. “Finding ways to contribute in your country, in your state, in your city, in your neighborhood … is truly the richest, best part of life,” she says. “There is nothing you can buy or consume or experience that will create a deeper sense of joy and fulfillment.” — NG

Hanna Skandera

Years before leading one of the Rocky Mountain region’s largest foundations, Hanna Skandera stood on the other side of its impact — as a Daniels Fund grantee while serving as New Mexico’s secretary of Education. Since 2020, she’s led the $1.7 billion Daniels Fund with that same bold vision, while honoring founder Bill Daniels’ legacy. Daniels — who brought Utah its first professional sports team, the American Basketball Association’s Utah Stars — pioneered the Daniels Scholarship Program, which has awarded over 5,000 college scholarships across four Mountain West states.

Skandera doesn’t shy away from complex issues, meeting them head-on by investing in scalable solutions. Her Big Bets strategy has already catalyzed over $433 million in funding partnerships. A former college track athlete and coach currently serving on the steering committee for the 2034 Utah Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, Skandera has led the fund to invest in youth sports access, supporting organizations like Utah’s National Ability Center. “It’s about more than the game,” Skandera says. “It’s about giving young people across Utah and throughout America the confidence and opportunity to chase their dreams.” — Valerie Braylovskiy

Jim Sorenson

Jim Sorenson’s journey into philanthropy began with a pivot. In the early 2000s, his video conferencing company was struggling after the dot-com bust when a brother-in-law who was deaf introduced him to a new service enabling real-time communication between deaf and hearing people via remote interpreters. Sorenson shifted focus to serve that niche, and Sorenson Communications was born. The company quickly became both a financial success and a transformative force for the Deaf community — helping make users four times more employable.

That experience sparked a realization: Social problems could be solved through scalable businesses that also attracted investment capital. For more than two decades, Sorenson has applied that insight, becoming a leading figure in impact investing — directing both market-rate and philanthropic capital toward underserved communities. His Sorenson Impact Group runs an advisory arm, invests in funds targeting disabilities, affordable housing and other social determinants of health, and supports the Sorenson Impact Institute at the University of Utah to train the next generation.

Unlike most perpetual foundations that invest 95 percent of assets without regard to mission, Sorenson’s foundation invests its entire corpus in alignment with its purpose, seeking a “double bottom line” of financial return and measurable social good. He calls his approach “catalytic philanthropy,” where the impact far exceeds the size of the initial donation.

One example he admires: the MacArthur Foundation’s $25 million loan guarantee that leveraged over $1 billion in small-business loans for sustainable agriculture, energy and communities in Africa and Latin America.

“We’re reaching about 1.7 billion people globally through the businesses, funds and investments we’ve made. That’s a ripple effect that is great to be part of,” Sorenson says. “And we hope that by building this ecosystem, we’re helping others to be able to experience the same thing.” — JH

The Larry H. & Gail Miller Family Foundation

For Larry and Gail Miller, business success was always inseparable from community responsibility. That ethos of stewardship is now carried forward through the Larry H. & Gail Miller Family Foundation, which channels the family’s resources into strengthening the social fabric of Utah and beyond. The foundation’s multi-generational giving is rooted in five pillars—health and medicine, shelter and food security, education and skill development, jobs and economic self-reliance, and cultural and spiritual enrichment.

What distinguishes the Miller family foundation is not simply the scope of its giving, but the philosophy behind it. The foundation’s impact principles emphasize listening closely to community voices, prioritizing outcomes over outputs, and building collaborations that amplify results.

To foster collaboration, the Miller family harnesses their convening power by gathering 200 philanthropists and community leaders annually to share best practices, discuss pressing issues and find ways to do good together.

In 2024, the Larry H. & Gail Miller Family Foundation awarded more than $40 million in grants to nonprofits across all 29 Utah counties. As part of this effort, the Foundation prioritized rural communities through its General Operating (GO) grants.

At the same time, the foundation has launched an ambitious place-based philanthropy effort. The Westside Community Grant Initiative, introduced in 2024, provided 38 grants to strengthen nonprofits serving Salt Lake City’s westside neighborhoods. These investments are helping to expand access to healthcare, education, economic opportunity, and cultural enrichment—ensuring this diverse and vital part of Utah’s capital city continues to thrive.

All of this reflects what the Millers describe as a “virtuous cycle”: as the Larry H. Miller Company grows, its success fuels philanthropic investments, which in turn strengthen the very communities that sustain that growth. It is a legacy of love, leadership, and long-term thinking—an investment not only in today’s needs but in the resilience of generations to come. — JH

Hali Lee

Growing up in Kansas City, Hali Lee watched her parents take part in a geh — a Korean tradition of pooling money into a pot and taking turns receiving it. Lee adapted this practice to philanthropy, called a giving circle, founding The Asian Women Giving Circle over 20 years ago. It has since granted over $1 million to support creative projects by Asian American women in New York City. A longtime advocate for diversifying philanthropy, Lee also co-founded the Donors of Color Network and more recently, Radiant Strategies, a boutique philanthropy consulting practice. Her new book, “The Big We,” is all about reimagining philanthropy as community action. — VB

Meg Whitman

During her tenure as eBay’s CEO (1998-2008), Whitman grew annual revenue from $4 million to $8 billion, enabling her and her husband, Griffith Harsh, to establish a charitable foundation in 2006 that, as of 2023, held assets worth $156 million. Yet Whitman’s philanthropic philosophy transcends mere financial contributions. She believes everyone can make an impact by giving not just money, but time and effort, as well as intellectual and social capital. This includes accepting board positions and advisory roles, particularly in her foundation’s focus areas: education and environmental causes. Whitman maintains that philanthropic commitment strengthens essential institutions, spurs innovation and creates social bonds through collaborative effort, ultimately building a more enduring society. — EB

Lisa Eccles

In 1989, fresh out of the University of Utah with her art history degree, figuring she’d now travel the world and maybe find work at a museum somewhere exotic, Lisa Eccles agreed to a part-time job with the charitable foundation started by her Uncle George and Aunt Lolie, a position she thought would last “maybe six months, a year tops.”

Then she discovered something unexpected: how good it felt to write checks to people and causes that really needed the help.

Thirty-six years later, she’s still writing them.

Today, the George S. and Dolores Doré Eccles Foundation’s presence is felt in every corner of the Beehive State; a synonym, as is the Eccles surname, for service and giving. But in 1989, when Lisa Eccles started, it was largely an unknown entity. Foundations in general were relatively new, especially in Utah.

They gave her a desk, a letter opener and a telephone in the First Security Bank building on Main Street in downtown Salt Lake City. She was the foundation’s sole employee, advising a three-person board — her father, Spencer Eccles, among them — on nonprofit grant proposals. When the board approved funding, Lisa Eccles made sure the paperwork was in order. She even hand-wrote the checks.

“It was such a profound moment for me,” she remembers, “sitting in my office, by myself, thinking what a joy, knowing these funds were going to help our community — even though I didn’t know the end user specifically, I knew we were making a difference.”

What began as a part-time job became a vocation. Three years in, her role became full time. A few years after that, she was invited to join the board. Since then, she has steered the foundation’s growth with a steady hand and a deeply personal sense of purpose.

In 1989, the foundation awarded $4.9 million in grants to 80 projects. Today, it distributes more than $27 million annually to around 400 projects — supporting everything from health care and education to the arts, social services, and conservation. Notable gifts include $70 million toward the University of Utah’s medical school (combined with another Eccles foundation for a total of $110 million) and $75 million in 2025 to build a new hospital in West Valley City — the foundation’s largest ever grant.

Since 1982, the foundation has granted nearly $1 billion while also growing its endowment to $1 billion — proof of its financial stewardship and philanthropic reach. — Lee Benson

Utah’s Promise

When Utah’s Promise formed in July 2023 — combining United Way of Salt Lake, Promise Partnership Utah, 211 Utah and Utah’s Promise Philanthropic Alliance — it was more than a rebrand. What began as the Salt Lake Charity Association in 1904 has evolved into an organization that fully embraces what philanthropists call “collective impact” to improve outcomes for children and families. President and CEO Bill Crim says its behind-the-scenes role is by design. Rather than acting as a funder, Utah’s Promise serves as the backbone for teamwork across sectors — the heart of collective impact. “Utah has a high degree of social cohesion and capital,” Crim says. “When you couple that with rigorous collective impact practice and relentless focus on results, that’s the winning formula.” That formula is already working. Promise Partnership Utah, a cradle-to-career initiative, unites public and private partners across eight Wasatch Front communities and six school districts. In Millcreek and South Salt Lake, the goal is that by 2028, 100 percent of students will graduate high school with a career plan and have their basic needs met. The name “Utah’s Promise” is intentional, a commitment that no child is left behind. — VB

Walton Family Foundation

Helen Walton — co-founder of Walmart and, later, the Walton Family Foundation — had a favorite saying: “It’s not what you gather in life, but what you scatter in life, that tells the kind of life you have lived.” The foundation she and her husband Sam Walton left behind has chased that mission statement since 1987, through funding programs that improve education and protect watersheds in northwest Arkansas, the Arkansas-Mississippi Delta and the country at large. There’s even a Walton Family Foundation office in Colorado, since much of the foundation’s environmental work involves advocating for and researching the water shortages impacting the Colorado River. — NG

Marriott Daughters Foundation

More than a decade ago, sisters Julie, Sandy, Karen and Mary Alice formalized a family tradition of generosity by founding the Marriott Daughters Foundation. Built on the legacy of their parents’ transformative institutional gifts (think Brigham Young University’s Marriott Center or a $25 million gift earlier this year to the University of Utah to launch a hospitality program) the sisters have steered their foundation toward education and health care, with a personal twist.

For Mary Alice Hatch, that means an especially deep commitment to women’s health, including funding millions in endometriosis research — an effort inspired by her own daughter’s diagnosis. But it’s also important to think local, she says. “It’s important to improve the community you live in, not just make these huge gifts,” she says. That philosophy has led to support for everything from a drama program at San Clemente High School to the Seacoast Symphony, which brings Los Angeles musicians to Dana Point.

Her parents’ foundation gives away 5 percent of its assets annually, with each of the sisters’ children granted a one-time gift of $25,000–$50,000 to support causes they care about — whether welding scholarships at Utah’s MTech colleges or local nonprofit initiatives. The goal: train the next generation to see philanthropy as a responsibility, not an afterthought.

That sense of duty extends beyond the family. The Marriotts joined Bill Gates’ Giving Pledge, committing part of their wealth to charity and encouraging peers to do the same. “You have an obligation,” Hatch says, “when you’ve been given so much.”

From funding cutting-edge research to underwriting community theater, the Marriott Daughters Foundation embodies a blend of high-impact giving and grassroots investment. It’s a model rooted in the belief that philanthropy isn’t just about moving the needle on big problems — it’s also about making life tangibly better, right where you are. — JH

Benefit Chicago

A nonprofit that employs homeless and low-income people to work for local companies; a hydroponic farm in the inner city that grows fresh produce for underserved neighborhoods; a beekeeping company that enlists the formerly incarcerated to harvest fresh honey. These are the resources that have grown through Benefit Chicago, a collaborative effort formed by the Chicago Community Trust, MacArthur Foundation and Calvert Foundation in 2016. Benefit Chicago invests more than $100 million in nonprofits and social organizations across the city that focus on job creation, food justice, education, child care, affordable housing and energy conservation. It’s a hopeful model of how philanthropies across the country can uplift low-income and underrepresented groups in their own communities. — NG

Celina De Sola

Born in El Salvador, Celina de Sola’s childhood was split between her homeland and the United States. She “knew intuitively that something wasn’t right,” given the visible disparities among children, which led to the 2007 founding of Glasswing International — an organization that invests in kids across Latin America and the U.S. De Sola’s approach emphasizes community collaboration. “We can’t assume we know the answers,” she says. “We can’t assume we know what people want or need.” Start with humility, she believes. Then listen and help where you can. She prioritizes mental health and unlocking kids’ potential, but she believes in philanthropy’s broader promise. “Change in society starts at the individual level,” she says, “with each of us.” — EB

Christy Turlington Burns

From the runways to the boardroom, fashion model-turned-philanthropist Christy Turlington Burns founded her organization, “Every Mother Counts,” after she experienced a childbirth complication. Since then, the former face of Calvin Klein has donated, raised and disbursed tens of millions of dollars toward improving global maternal health. —EB

Elizabeth Alexander

President of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation — the nation’s largest arts and humanities funder — Elizabeth Alexander has pioneered grants supporting diversity, like the Jazz Legacies Fellowship and the Monuments Project, which preserves and funds historical monuments. An esteemed scholar and poet, Alexander taught at Yale for over 15 years and was twice a Pulitzer Prize finalist. — VB

N. Clay Robbins

Chairman and CEO of Indiana’s Lilly Endowment Inc., N. Clay Robbins led the foundation to increase its giving to more than $2.2 billion last year. The country’s second-largest private foundation, focusing on community development, education and religion, has awarded $100 million grants to institutions like Purdue University and the National Park Foundation. — VB

Badr Jafar

Badr Jafar — CEO of Crescent Enterprises and United Arab Emirates’ Special Envoy for Business and Philanthropy — got involved in strategic philanthropy in 2010, when he founded the nonprofit Pearl Initiative to advance corporate governance in the Gulf region. A decade later, he became the founding patron of strategic philanthropy centers at two different universities, and most recently published “The Business of Philanthropy.” — VB

Oprah Winfrey

Oprah Winfrey, dubbed the “queen of all media,” is also a celebrated philanthropist — contributing over $400 million to organizations that serve children, families and communities through her foundation. In 2004, Winfrey was the founding, single largest donor to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. She opened the Oprah Winfrey Leadership Academia for Girls in South Africa in 2007, transforming the lives of over 525 graduates from disadvantaged backgrounds. — VB

The Audacious Project

The Audacious Project, housed at TED since 2018, is a collaborative funding initiative that’s invested more than $6.6 billion in the world’s most promising changemakers. More than $725 million was raised to support the 2024 cohort, and their 10 social innovations. Projects ranged from large-scale coral restoration across Australia and the Pacific using heat-tolerant corals to an AI-powered system that repurposes generic drugs for life-changing treatments. — VB

Emergent Ventures

Run by Mercatus Center faculty director Tyler Cowen at George Mason University, Emergent Ventures launched in 2018 to support entrepreneurs with “zero to one,” high-reward ideas. Focused on India, Africa and the Caribbean, and Ukraine, the fellowship and grant program awards ideas from people around the world — past projects included spreading 3D printers in rural Taiwan and using sanitation robotics in Ugandan medical centers. — VB

Rural and Indigenous investment

While only 20 percent of large funders give to Indigenous causes, more are recognizing the value of investing in Indigenous and rural communities. Utah’s Center for Rural Development, within the Governor’s Office of Economic Opportunity, supports economic development in the state’s rural counties through competitive grants, like providing $500,000 to fund Beaver County’s road upgrade for an industrial park. — VB

LOR Foundation

LOR, a place-based and private foundation, works with rural communities in the Mountain West on immediate and long lasting-impact solutions across areas like education, housing, the environment and health. In 2025, LOR’s Field Work initiative — focused on mental health in rural places — invested a total $500,000 in 26 projects, such as on-call peer support for first responders in rural Colorado, and a network of social interaction for senior citizens in Clearwater County, Idaho. — VB

Jacob Pruitt

As president of Fidelity Charitable, the country’s largest donor-advised fund, Jacob Pruitt oversaw nearly $15 billion in grants last year — nearly twice as much as the Gates Foundation. A donor-advised fund offers individual donors up-front tax deductions but still gives them some control over how their money is disbursed. Pruitt has encouraged the organization to embrace technology, including cryptocurrency, which unlocked $786 million in new donations in 2024. — EB

Katherine Lorenz

Leading the Cynthia and George Mitchell Foundation, Katherine Lorenz trailblazes the “nexus of environmental protection, social equity, and economic vibrancy” in Texas by spearheading donations to causes like clean energy and sustainability science. But she also leads the “Giving Pledge Next Generation group,” or “Next Gen” — an outgrowth of the original Giving Pledge that encourages the signatories’ descendants to continue their families’ philanthropic legacies and uphold their commitments. — EB

30 Jack Ma

Best known for founding the Asian e-commerce giant Alibaba, Jack Ma has also become one of the biggest names in global philanthropy. His nonprofit’s initiatives range from support for entrepreneurship and education in Africa and around the world to promoting women’s leadership, including via funding for the China women’s national soccer team. — EB

Artis Stevens

President and CEO of Big Brothers Big Sisters of America, Artis Stevens has transformed the nonprofit in the past five years. With experience at the National 4-H Council and Boys & Girls Club of America, Stevens has led BBBSA to double its funding, mentor kids and teenagers, and increase membership. — VB

Pierre and Pam Omidyar

After founding eBay in 1995, Pierre Omidyar and his wife, Pam, decided to use their fortune to improve humanity. They’ve since given over $4 billion to causes including strengthening civic institutions, supporting independent journalism, addressing youth mental health and ensuring AI is beholden to democracy. — EB

TGR Foundation

Established by Tiger Woods to bring golf to kids, the TGR Foundation now encompasses a 35,000-square foot “Learning Lab” campus in Southern California; satellite locations across the country; and a wider focus on youth empowerment and education. The foundation has received consecutive four-star ratings from Charity Navigator since 2012. — EB

Lever for Change

An outgrowth of the MacArthur Foundation, Lever for Change was founded in 2019 to drive billions in philanthropic funding toward “bold solutions” to our greatest problems, “including racial inequity, gender inequality, economic opportunity and climate change.” It has granted more than $2.5 billion toward a goal of unlocking $10 billion for proven problem solvers by the end of 2030. — EB

Stand Together

Industrialist Charles Koch’s 2003 initiative employs data-driven grantmaking through its trademarked “Customer First Measurement” system, which collects feedback from program beneficiaries to guide funding across economic development, health care, foreign policy and limited government initiatives. — EB

The Other Side Village

This experimental solution to chronic homelessness opened late last year in Salt Lake City by offering not just stable, cottage-style housing, but also a network of peers to encourage accountability, structure and life skills development. The program initially built 60 homes, with hopes of eventually reaching 430. — EB

Warren Buffett

Over the last couple decades, 95-year-old philanthropist Warren Buffett donated about $60 billion to causes that combat issues like world hunger and human trafficking. Buffett, the seventh-richest person in the world, is honoring his 2006 pledge to donate more than 99 percent of his wealth in his lifetime. — NG

Asha Curran

As CEO and co-founder of GivingTuesday, Asha Curran oversees a radical generosity movement that’s mobilized millions of people across six continents to give back to their communities by pursuing volunteer opportunities on the Tuesday after Thanksgiving. Curran helped nonprofits across the country raise $3.6 billion in a single day last year. — NG

John Palfrey

The MacArthur Foundation distributes about $400 million in grants to nonprofits each year to support causes like climate action and justice reform. In light of federal funding cuts, MacArthur Foundation President John Palfrey plans to give an additional $80 million a year for the next couple years “so (nonprofits) can weather this period of disruption.” — NG

Faith-based philanthropy

Among the largest is Catholic Charities, whose network of agencies operating independently under 168 dioceses last year provided food, housing and disaster relief to millions, all in the name of living out its religious values. Similar organizations abound across different faiths, from Quakers and Muslims to evangelicals and Latter-day Saints. — EB

Community Foundation of Utah

The Community Foundation of Utah is a “community convener” that collaborates with nonprofits, businesses and individuals to ensure philanthropies leave a local impact. Last year, the foundation’s grants and funds supported causes like preserving the Great Salt Lake’s watershed and bringing computer science programs to 4-H clubs and afterschool programs for rural youth. — NG

Jeff Atwood

In 2021, tech entrepreneur Jeff Atwood sold Stack Overflow, an online informational network for computer programmers, for $1.8 billion. Rather than hoard that fortune, Atwood announced earlier this year that he plans to donate half his wealth within the next five years to combat American wealth inequality. — NG

Big Bang Philanthropy

As a funder network, Big Bang Philanthropy works with members who dedicate at least $1 million annually to mitigate poverty in low- and middle-income countries. Their money goes to groups like Educate Girls, which grants girls in rural India access to education, and mothers2mothers, which employs women living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. — NG

Give Directly

Why not cut out the middleman? That’s the guiding principle behind GiveDirectly, which donates cash to individuals around the world, not large organizations. GiveDirectly believes financial autonomy can accelerate the end of extreme poverty, whether that’s helping a young adult in Malawi buy life-saving farm equipment or a mother in Michigan afford prenatal and infant health care. — NG

Groundbreak

The GroundBreak Coalition is a group of more than 40 corporate, civic and philanthropic partners building a new financial system in Minnesota that can be translated across the country. The coalition is investing in a more racially equitable middle class, creating thousands of new and diverse homeowners, entrepreneurs and jobs in the Minneapolis-St. Paul region. — NG

Mortenson Family Foundation

With a board of directors featuring nine people named Mortenson, this Minnesota-based effort prioritizes family, from its leaders to its projects, with a particular interest in “impact investing” — meaning it funds a “big impact umbrella” that seeks positive social outcomes. — EB

Housing for Impact

This Utah-based partnership between two housing-focused nonprofits has promised to build 850 affordable units across the Wasatch Front over three years. Clark Ivory, leader of Ivory Homes, the largest homebuilder in Utah, and the nonprofit Ivory Innovations, announced the opening of 240 such units in Lehi by declaring that the group is trying to “create a place where families and individuals can thrive.” — EB

Michael Bloomberg

Michael Bloomberg was 2024’s top donor, giving $3.7 billion, per the Chronicle of Philanthropy. His gifts included $1 billion to Johns Hopkins to make medical school free for most students and $600 million to bolster medical-school endowments at four HBCUs. — JH

Li Ka-Shing

At 96, Hong Kong tycoon Li Ka-shing — known as “Superman” for his business acumen — remains one of the world’s top philanthropists. He has given more than $3.8 billion since 1980, with recent gifts supporting cancer research, medical technology, and entrepreneurship at leading universities. — JH

Melinda French Gates

Gates co-founded the Gates Foundation in 2000, then founded Pivotal Ventures in 2015 to focus on advancing the power and influence of women around the globe. She pledged to contribute $1 billion through 2026 to causes like improving women’s health and breaking workplace barriers. — NG

This story appears in the October 2025 issue of DeseretMagazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.